On December 11, 2014, Portland State University’s board of trustees voted to deputize and arm PSU’s Campus Public Safety Officers (CPSO). The decision was made with a nine to three majority and drew immediate criticism. Advocates of armament, including then university president Wim Wievel, suggested armed police would ensure campus safety.

The board’s 2014 decision came at a moment of widespread anxiety concerning police violence in America. Less than a month before the vote, on November 22, 2014, Cleveland police officers Timothy Loehmann and Frank Garmback shot and killed Tamir Rice, age 12. Two days after Rice’s killing, a Ferguson Missouri court declined to indict Darren Wilson, the officer responsible for the killing of Mike Brown. Ferguson was still in flames as CPSO officers gained authorization to patrol with lethal weapons.

CPSO armament would not take effect until July of the following year. The board of trustees needed time to update policies and iron out the details of this radical change to campus public safety. In the meantime, 2015 would reveal itself as a record breaking year for police killings in the U.S., as the April killing of Freddie Gray in Baltimore sparked renewed protests. Gray’s killing was no anomaly; according to a study by the Guardian, U.S. police killed 1,146 people in 2015.

These concerns about racism in American policing had statistical merit. According to the same Guardian study, young Black men between the ages of 15-34 were nine times as likely as other Americans to be killed by law enforcement, despite making up just 2% of the U.S. population. One out of every 65 deaths of a young Black man in the U.S. was at the hands of the police in 2015, the study found.

PSU’s board of trustees could not have known this when they voted to approve the armament of CPSO in December of 2014, but with regard to police violence, 2014 was hardly better than 2015. We know the names of Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, and Mike Brown, but these were just three of over a thousand individuals killed by U.S. police in 2014.

Opposition to arming campus public safety officers at PSU was strong from the beginning. In December 2014, the PSU faculty senate passed a resolution opposing the creation of an armed campus police force. Citing chilling rates of sexual assault perpetrated by U.S. law enforcement, the resolution expressed concern over the potential for gender based and racialized violence at the hands of sworn officers. Moreover, the resolution cited the overrepresentation of mentally ill individuals among victims of police violence, corroborated by the Guardian’s 2015 report. Roughly 10% of those killed by U.S. police in 2015 were in a state of mental distress.

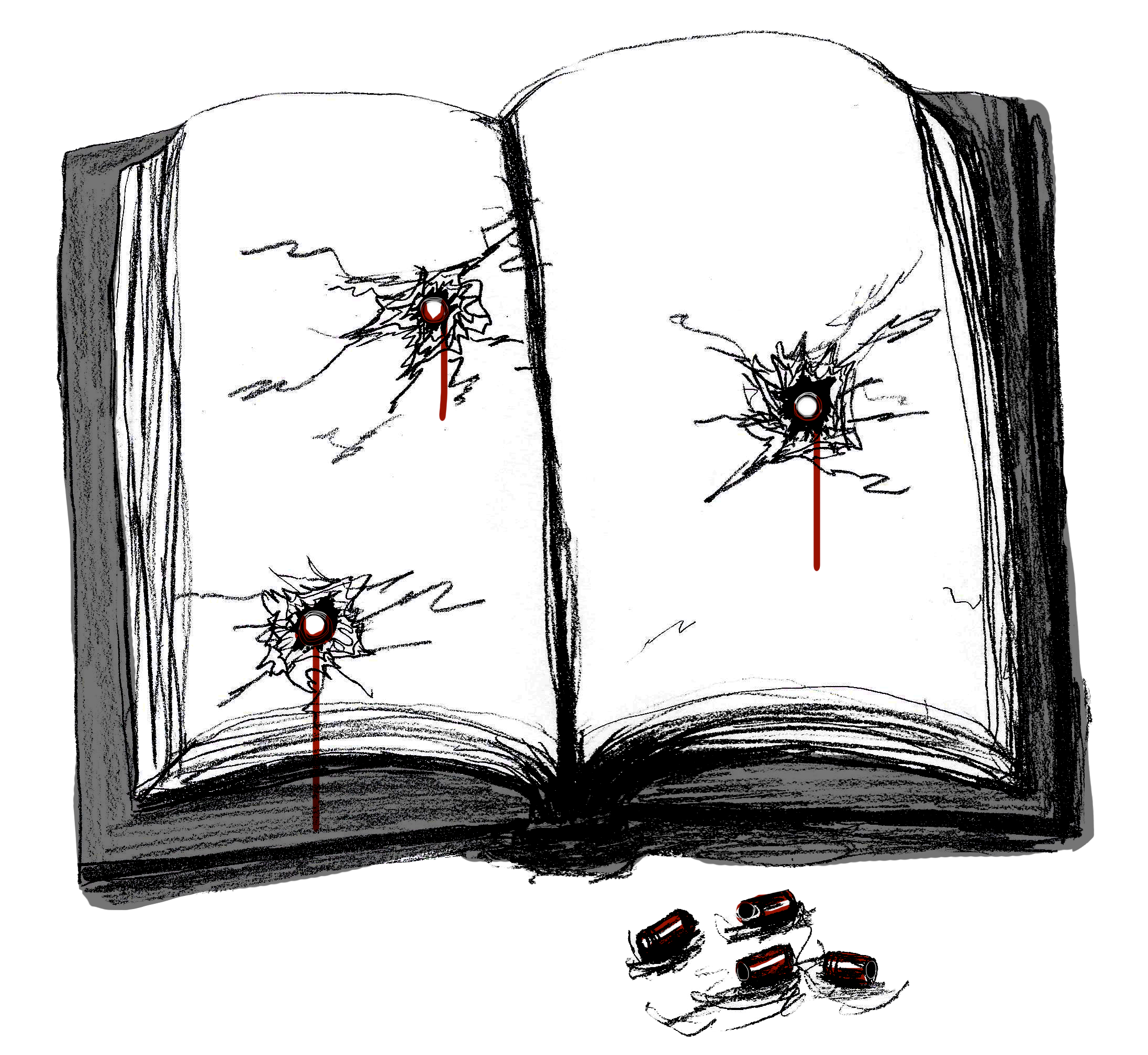

illustrations by May Walker

Since 2015, PSU’s School of Social Work, School of Gender, Race, and Nations, Department of English, and Department of Psychology have issued public statements or open letters calling on the University to disarm CPSO. Disarmament has been officially supported by every academic union at PSU, including the PSU chapter of the American Association of University Professors, the Portland State University Faculty Association, and PSU’s Graduate Employees Union. In fact, every faculty union at every public Oregon university supports the disarmament of campus public safety officers. Despite widespread support, it would take years of advocacy and a series of tragic events for PSU’s administration to consider reversing its 2014 decision.

The emergence of university law enforcement

Campus policing is a relatively new institution, mostly dating to the 1960s and 70s. Law enforcement emerged on university campuses during this period in response to student organizing and activism, writes John J. Sloane, Professor Emeritus of Criminal Justice at the University of Alabama-Birmingham. Campus police departments were established to maintain order in the face of student led Civil Rights protests and campus opposition to U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. “Essentially, university police forces were created not to protect students from harm,” writes political analyst Angela Wright, “but to protect the university from its students.”

In a recent New Yorker article, columnist and Princeton University professor Keeanga Yamahtta-Taylor signals that the impetus for expanded campus policing in the 1960s and 70s corresponded to a shifting tendency in U.S. law enforcement more broadly. “During the civil rights movement, police were the shock troops for the massive resistance of the white political establishment in the American South,” Yamahtta-Taylor writes. “By the mid-sixties, policing and the criminal justice system were being retrofitted as a response to a growing insurgency in Black urban communities.”

In other words, the post-war period witnessed a transition in the central role of policing in America. In the nineteenth century, policing had largely functioned as a mechanism to defend regimes of property, exploitation, and extraction, such as slavery; in the early twentieth century, it had been integral to disciplining the urban industrial working classes, who were agitating for expanded rights and labor protections; by the mid-twentieth century, American policing was beginning to be used as an instrument of direct political repression in the face of burgeoning leftist movements.

From the 1980s onward, campus law enforcement agencies proliferated in lockstep with the expansion and militarization of U.S. policing. Campus police increasingly resembled their municipal counterparts. Yet where municipal police tend to have a chain of command leading back to elected officials, and hence to voters, campus police usually lack any such accountability. In most cases, including at PSU, campus police are accountable to university presidents or unelected boards of trustees. Hence, the communities policed by campus law enforcement generally lack robust, formal mechanisms for keeping officers and departments accountable. University police forces are “largely exempt from the ‘basic idea of voter accountability,’” University of Pennsylvania criminologist Emily Owens told The Atlantic.

By the time PSU deputized and armed its CPSO in 2015, 92% of public universities in the U.S. had similar law enforcement agencies, The Atlantic reports. Of these, some 94% were armed with handguns and chemical agents such as pepper spray. 81% of campus police forces were authorized to patrol off campus areas, and 86% were able to make arrests. As the militarization of campus law enforcement has proceeded together with that of police agencies more broadly, campus policing stands today as an integral appendage of municipal law enforcement, especially in urban areas.

Jason Washington and the movement to Disarm PSU

For many early advocates of armament at PSU, the ubiquity of armed campus law enforcement spoke for itself. Since the majority of other public universities employed armed police forces, it was natural that PSU should do the same. In this way, conformity with prevailing standards, rather than strong arguments based on empirical data, guided the board’s 2014 decision to arm, Dr. Miranda Mosier of PSU’s School of Social Work told The Pacific Sentinel. “Compared to our competitor institutions, we were the only ones who weren’t armed,” Mosier said. Indeed, the existence of police was self justifying for then president Wiewel and for many board members. Extensive data challenging the efficacy of policing, offered to the board in the faculty senate’s December 2014 resolution, was of comparatively little importance.

Advocates of campus policing have long argued that university law enforcement is more attuned to campus community dynamics than municipal police or county sheriffs. Thus, campus police are particularly well situated to deal with the complexities of the campus landscape. However, in recent years campus police have invited many of the same criticisms as their municipal counterparts. Criticism has centered on the disproportionate use of force against Black people and other marginalized groups.

The threat of police violence was a central concern to early opponents of CPSO armament at PSU. Drawing on critiques of militarized police generally, the PSU Student Union (PSUSU) rallied around the call to “demilitarize PSU” in 2014, even before armement was put to vote. “We see what’s happening with police brutality all over the United States,” Christina Kane, a student and member of PSUSU told the board of trustees at a November 2014 meeting. “In the wake of Ferguson, in the wake of all the murders… we think [arming CPSO] would disproportionately affect marginalized communities on campus.”

Less than four years later, the fears of Kane and many others who opposed CPSO armament would be confirmed. On June 29, 2018, PSU campus police officers James Dewey and Shawn McKenzie shot and killed Jason Washington. Mr. Washington was a 45 year old postal worker and U.S. Navy veteran and a Black man. He was attempting to de-escalate a fight outside the Cheerful Tortoise on SW 6th Ave and College St. when he was killed.

Jason Washington was a registered gun owner with a valid concealed carry permit in the state of Oregon. At the time of his death, he was in possession of a handgun belonging to his friend, Jeremey Wilkinson. Washington had taken possession of Wilkinson’s gun earlier in the night to prevent him from making a “poor decision,” OregonLive reported. Officers were responding to reports of a fight involving Wilkinson.

When officers McKenzie and Dewey arrived on the scene, Washington was retrieving the weapon, which had fallen out of its holster. Officers McKenzie and Dewey opened fire one second after commanding Washington to drop the gun, according to body camera footage reviewed by OPB. The two white officers fired 17 rounds in 15 seconds, the Portland Tribune reported. Washington was struck nine times and was pronounced dead when paramedics arrived on the scene.

A grand jury found officers McKenzie and Dewey justified in killing Washington.

Although campus organizing around CPSO disarmament had been ongoing at PSU since 2014, momentum had stalled in the semesters leading up to Washington’s death. “Pretty much overnight, after Jason Washington was killed, [the movement to disarm CPSO] started up again,” said Olivia Pace, a PSU alumna and longtime advocate for CPSO disarmament.

Pace and other members of PSUSU held a rally the week after Washington was killed, drawing hundreds of community members to downtown Portland. In September 2018, they occupied the plaza at SW Broadway and Mill for ten days, putting a spotlight on PSU’s role in Washington’s killing. Over the course of the occupation, they collected over 6,000 signatures on a petition calling for immediate CPSO disarmament. Hundreds of pages of signatures were delivered to an indifferent board of trustees at their October 2018 meeting.

Following Washington’s killing, calls for disarmament reverberated throughout the community. Jo Ann Hardesty, a candidate for Portland City Council at the time of Washington’s death, recalled the history of resistance to an armed police force on PSU’s campus. “Community members and staff and faculty were very, very concerned about arming the police,” Hardesty told CBS News. “We knew then that somebody would die, and here we are… [W]e knew it would happen—we just didn’t know when.”

Following the Board of Trustees meeting in October 2018, PSU launched an internal investigation into CPSO’s policies and protocols. They hired an independent security review firm, Margolis Healy, to analyze CPSO policies and to make campus safety recommendations. In the face of those calling for disarmament and reductions to the campus policing budget, Margolis Healy recommended an expansion of CPSO’s staff, additional physical security infrastructure on campus, and ongoing armed policing at PSU.

Margolis Healy’s report found that 52% of the campus community supported disarming CPSO, while only 37% supported the retention of armed officers. These numbers notwithstanding, the board of trustees adopted Margolis Healy’s recommendations, voting to retain armed campus police in June 2019.

National resistance to campus policing

The expansion and militarization of campus police has been met with resistance across the country. Student organizers, as well as faculty and community groups, are expressing discomfort with various facets of the system of campus policing. They are organizing themselves in creative ways and issuing calls for substantial changes to prevailing models of public safety.

Organizing against campus policing had been ongoing at the University of Chicago for nearly a decade. Student groups and community activists in particular have resisted what they see as campus police’s active role in gentrifying the neighborhoods surrounding the University. “The push to decrease crime [in and around the University of Chicago] came at the cost of exclusion and trauma for Black residents,” Ashvini Kartik-Narayan wrote in 2018.

The same year, the struggle against campus law enforcement was reignited when University of Chicago police shot a student suffering a mental health crisis. Student groups called on the university to disarm security officers while decreasing their funding and jurisdiction. Critics of policing at the prestigious midwestern institution argued that reducing the University of Chicago Police Department’s broad jurisdictional privileges would limit the department’s ability to overpolice nearby historically Black neighborhoods.

Like their peers in Chicago, University of California students have long resisted what many see as a politically repressive and racist culture in campus policing. UC police first attracted national attention in 2011, when a photo depicting a UC Davis officer casually pepper spraying a row of seated students engaged in an Occupy protest went viral. The university drew further criticism in 2015, when it paid a communications firm $175,000 to “eliminate references to the pepper spray incident on Google,” the Guardian reported. In 2018, campus police at UC Berkeley were accused of excessive force after arresting 17 graduate students engaged in a labor strike, and a 2019 poll found that only 34% of Black students at UC Berkeley trusted campus police.

Students and faculty across the University of California system in May 2021 participated in a “Day of Refusal”—a virtual strike with the single demand that the university remove all campus police from all UC campuses. This call for the total removal of campus law enforcement reflects a national trend in opposition to campus policing. In the wake of the 2020 killings of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor, many student organizers are asking for more than reforms. They are demanding a radical transformation of existing models of campus public safety.

This demand reverberates throughout some of the nation’s most prestigious universities. In June 2020, a coalition of students, faculty, and staff at University of Pennsylvania released a statement calling on the Ivy League institution to divest from and ultimately disband its campus police. The statement boasted 12,000 supporters and quickly garnered endorsement of 48 groups within the surrounding community, according to The Daily Pennsylvanian. The same month, an online petition calling for the abolition of campus police at Yale University garnered almost 9,000 signatures. In a school with roughly 13,400 students, that’s equivalent to 65% of the student body.

Additionally, Student activists at the University of Chicago have augmented their earlier demands. Now, they insist that the university work toward total abolition of its campus police by 2022.

Closer to home, University of Oregon students affiliated with the group Disarm UO have voiced dissatisfaction with reforms to campus policing implemented by the university’s administration last Fall. These reforms included an increased staff of unarmed campus safety officers, but no reduction in armed police. Such reforms, which amount to an expansion of the reach and budget of campus law enforcement, mirror changes made to PSU’s CPSO in 2019. “Disarm UO stands firm in our belief that guns do not belong on school grounds or college campuses,” Disarm UO organizers told KLCC, a local NPR affiliate. “What actually keeps students and the community safe [is] bolstering campus resources and non-police community safety initiatives.”

An abolitionist critique of university law enforcement

Many recent calls for defunding and disarming campus law enforcement employ an abolitionist critique of policing. This critique is premised on the idea that communities don’t need better policing structures, but less policing. Abolitionists insist that policing should be curtailed and ultimately replaced by services that allow communities and individuals to flourish.

“The emphasis in much abolitionist discourse and critique is on community restoration and repair,” says Dr. Adam Culver, instructor of political science and international studies at PSU. Police enforce laws which abolitionists say structurally disadvantage and harm marginalized populations; providing resources for these populations would work to eliminate the root causes of harm in communities. Our society tries to solve all of its problems with policing, Dr. Culver says, because we routinely conflate crime and harm. All things that are criminal are not harmful, however, and many things that are harmful are perfectly legal. Abolitionists imagine alternatives to policing with an eye towards harm reduction, arguing that much harm results from austerity, poverty, and deprivation.

Still, an abolitionist agenda should not be viewed as simply a new iteration of the traditional call for a centralized welfare state, Dr. Culver told The Pacific Sentinel. “The democratically organized and community driven, bottom up character of [abolitionism]” sets it apart from calls for institutional reform or expanded social services, Dr. Culver said, although abolitionists may also advocate for these things. Above all, abolitionism should be understood as an expansive program of social transformation. “An abolitionist agenda demands that our priorities be radically transformed.”

Those who advocate abolition of police and prisons don’t see these structures disappearing overnight. Rather, they argue that providing communities with resources is a more promising model of overall harm reduction than state surveillance, policing, and institutionalized punishment. Abolitionists advocate that this should be reflected in municipal, state, and federal budgets. Governmental spending should prioritize community based services and initiatives in direct proportion to decreases in spending on police and prisons. Moreover, the services and initiatives implemented should be responsive to needs on the ground and should, whenever possible, be organized by members of affected communities themselves.

“Abolitionist scholars talk about ‘reformist reforms’ and ‘abolitionist reforms,’” Olivia Pace told The Pacific Sentinel. Angela Y. Davis and Ruth Wilson Gilmore, prominent abolitionists who founded the national grassroots organization Critical Resistance in 1997, define “abolitionist reforms” as initiatives that reduce police funding, challenge the notion that police increase safety, and reduce the scale of policing. These can be counterposed to reforms such as increased police training or the use of body cameras. These latter programs tend to increase funding to police departments, and do nothing to challenge the bedrock assumption that community safety depends on the presence of police.

“Disarmament, to me, is an abolitionist reform,” Pace says. “It directly decreases the power and the monopoly of violence that police have.”

Disarming campus police alone does not amount to a comprehensive vision of community safety. Pace and other abolitionist organizers advocate redirecting the funds currently earmarked for armed campus police toward other resources. “The work of abolition is not about instantly defunding every department in every campus, town or city,” prominent abolitionists Angela Y. Davis, Melina Abdullah and Robin Kelley wrote in an op-ed earlier this year. “Rather, abolition is a process of strategically reallocating resources away from police and toward community based models of safety, support and prevention.”

Pace echoes this sentiment. Providing for the basic needs of the community—food, shelter, addiction and mental health services, trauma informed support and education surrounding sexual and gender based violence—would work to eliminate the root causes of harm on campus, she says. For Pace and other abolitionists, this represents a much more promising approach to public safety than police intervention after harm has occurred. More to the point, it works to reduce the violence and discrimination that abolitionists believe is endemic to policing.

The (dis)continuation of armed patrols

In the Spring of 2020, a series of events rendered PSU’s 2019 decision to retain armed campus safety officers politically untenable. The highly publicized killings of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor, among others, cast a renewed spotlight on issues of state sanctioned violence against Black people, and on racism in U.S. policing. Massive protests across the country drew the language of abolition from the margins of left wing political circles into the theaters of mainstream debate. Portland’s protests in particular demonstrated the local community’s intolerance for current standards in law enforcement.

Portland had seen nearly 80 continuous days of protests against police violence when PSU president Stephen Percy announced last August that CPSO would be discontinuing armed patrols. “The calls for change that we are hearing at PSU are ringing out across our nation,” Percy wrote in an email to the campus community. “We must find a new way to protect the safety of our community, one that eliminates systemic racism and promotes the dignity of all who come to our urban campus.” After nearly six years of student and faculty organizing, unarmed campus patrols would begin in Fall 2020.

Today, Spring term of 2021 has drawn to a close, and armed patrols continue on PSU’s campus. Significant delays to the promised discontinuation of armed patrols have resulted from bureaucratic and personnel problems, CPSO Chief Willie Halliburton told the community at a January 2021 forum.

Following Percy’s August announcement, two CPSO officers retired, and a third resigned, the PSU Vanguard reported. Halliburton highlighted these staffing problems to help explain the glacial pace of CPSO’s promised reforms. Halliburton did not respond to the Sentinel’s request for comment or clarification.

Other remarks made at the January forum raise further questions. Halliburton stated that following the discontinuation of armed patrols, CPSO’s relationship with the Portland Police Bureau “will change.” However, the specific nature of this change was not explained.

More importantly, the current plan to end armed patrols does not signal the disarmament of CPSO, strictly speaking. Rather, lethal weapons will be stored at the CPSO office, to be accessed under certain circumstances. There has been little transparency about what these circumstances are, and what protocols will govern officers’ access to firearms.

There remain questions about how proposed CPSO policy changes will affect the office’s overall budget. If the discontinuation of armed patrols affects a budget reduction, where will these funds be redirected? Will they be channeled toward resources to meet the basic needs of the campus community, or will they be reinvested in the same general model of campus policing the community has long resisted?

At the January 2021 forum, chief Halliburton expressed his “deepest steadfast commitment to unarmed patrols here at PSU.” Regarding the change, he stated, “it will happen. It will happen this academic school year.” As the 2021 academic year drew to a close, Halliburton’s promise remained unfulfilled.

A June 11 email from President Percy alerted the campus community that armed patrols will finally be discontinued no later than September 1, 2021, but over the years, PSU administrators’ lack of transparency and apparent indifference to community needs and wishes has eroded the trust of activists and community organizers. After multiple failures to meet stated deadlines, Percy’s recent email rings somewhat hollow. The email failed to acknowledge a year’s worth of delays and false promises with regard to disarmament, nor did it mention the third anniversary of Jason Washington’s killing, on June 29.

[For more information on the movement to disarm PSU and honor Jason Washington’s memory, follow @disarmpsunow on Instagram.]