“These are the times that try men’s souls.”

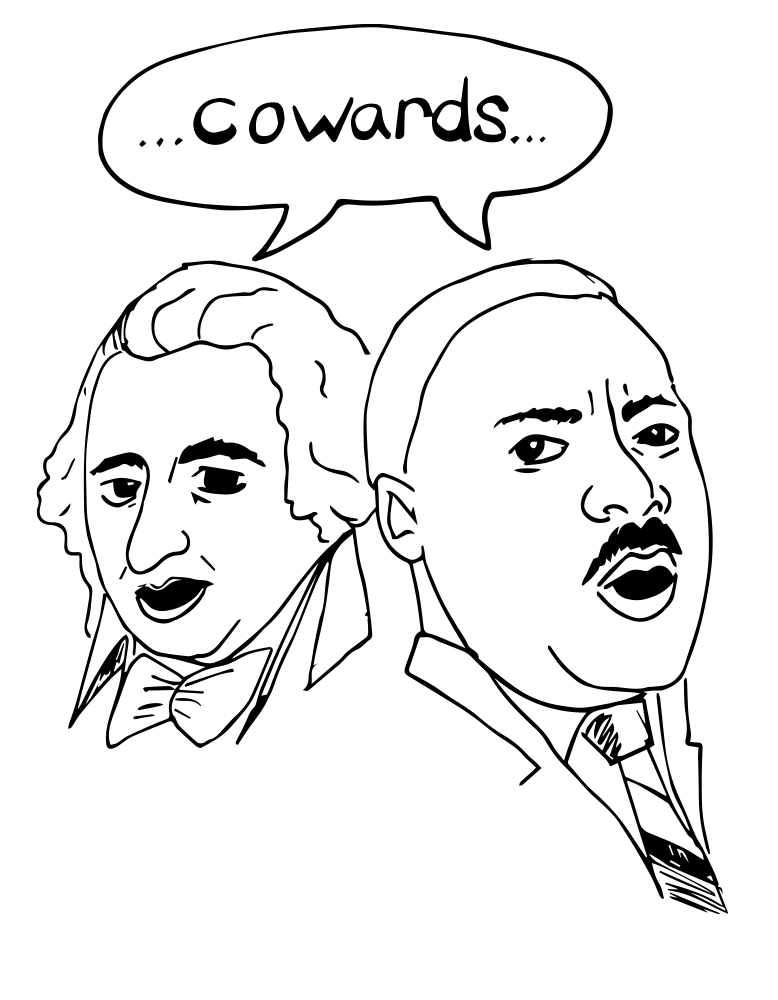

Those are the words that rang out like a thundercrack on December 23, 1776, in the first sentence of Thomas Paine’s wartime work The American Crisis. They are certainly words fitting for the Trump era. His pamphlet calling for independence, Common Sense, may be more remembered—but the Crisis was a work made in the heat of war, after independence had been declared. All thirteen volumes of the Crisis bristle with righteous indignation and fury against the tyrannies of Great Britain. But more importantly, they enunciate a clear goal: to expel tyranny and despotism of all forms, and protect liberty and equality at all costs. Paine had a particular disgust for so-called moderates who claimed to find a “middle ground” rather than fight for what was right.

He mercilessly mocks the British-supporting Tories of the colonies in the first volume: “Every tory [sic] is a coward, for a servile, slavish, self-interested fear is the foundation of toryism; and a man under such influence, though he may be cruel, never can be brave.” In volume three, he lambasts those who would wish for a reconciliation with Britain as the more “reasonable” option as a “lax manner of administering justice, falsely termed moderation…” In volume four, “Those who expect to reap the blessings of freedom, must…undergo the fatigues of supporting it.” It was in this cradle of fiery oratory and unabashed radicalism that American democracy was raised. The spirit of America itself, its ideals of universal freedom and human equality that it aspires to (though does not always meet) are inherently radical. And it is this radicalism, this unwavering commitment to human rights and democracy and equality that we should embrace, not run from.

illustrations by Jake Johnson

Let us now turn to Pete Buttigieg.

In a (now deleted) tweet posted during the Democratic Debate on February 25, the former presidential candidate decried both the “nostalgia for the social order of the 1950s” of Donald Trump and the “nostalgia for the revolutionary politics of the 1960s” of Bernie Sanders. One of these, clearly, is not like the other.

The 1960s were a period of revolutionary politics, to be sure. The revolutions of the 60s brought an end to Jim Crow and legally sanctioned segregation. They saw a resurgence of the women’s rights movement, the continuing civil rights movement, and the gay rights movement, culminating in the Stonewall riots of 1969. Without the turmoil and radicalism of the 1960s, the 1970s, 80s, 90s and beyond would have looked very different for anyone who was not white, straight, and male. All of this begs the question: why would Buttigieg, a liberal millennial and the first openly-gay presidential candidate, reject the politics that paved the way for him to be a public figure at all?

The most obvious answer is that it made for good politics, which is the issue I’d like to address here. Buttigieg’s base is overwhelmingly made up of older, more affluent voters who lived through the Cold War and all the terror and propaganda that came with it. A rebuke of “the 60s” is a well-worn, though effective dog-whistle that brings with it all kinds of implications—the “revolutionary politics” of the 60s brought with it the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, Roe v. Wade, Medicare, Medicaid, and countless other civil rights laws and social programs. Issuing a complaint about the “radical” politics of the 1960s is an easy way to connect with a center-right base who wants to go back to “how it was before.”

Compromise is not always the best course of action when it involves compromising on fundamental principles. “Compromise” in the name of moderation is often exploited by those on the fringes. “Meet me in the middle,” the extremist says. The moderate takes a step forward. The extremist takes a step back. “Meet me in the middle,” the extremist says.

Martin Luther King, Jr., in his 1963 letter from a Birmingham jail, wrote,

[T]he Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not…the Ku Klux Klanner but the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says, “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can’t agree with your methods of direct action…”

What Dr. King wrote then is equally applicable to today. We do not live in a time of justice. We live in a time of negative peace; a facade that has recently crumbled under the weight of the forces that propelled Donald Trump into office. Forty years of neoliberalism have left this country stuck between the center-right and the far-right, narrowing our window of acceptable political discourse and leaving us at the mercy of demagogues who wish to exploit that “negative peace.” On one side there are right-wing ideologues who want nothing more than to install their vision of an unjust, unequal society; on the other side there are feckless, hand-waving liberals who, through their fervent belief in “compromise” and “reasonability,” have given them free reign to do so.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the U.S. poverty rate in 2018 was 11.8 percent—38.1 million people. The Department of Housing and Urban Development estimated that on a single night in January 2018, 552,830 people experienced homelessness in the United States, one-fifth of which were children. A 2015 Kaiser Family Foundation/New York Times study found that 26% of U.S. adults reported difficulties or an inability to pay medical bills in the past 12 months. In the same study, 66% percent reported they had more difficulty from one-time events rather than chronic illness; among those with insurance, the problem reported most often was that their copays, deductibles, and coinsurance was more than they could afford. A 2017 study from the Economic Policy Institute found that median white wealth in the United States is twelve times higher than median black wealth, largely fueled by the gap in white and black homeownership.

These issues did not appear out of thin air. These problems do not just happen, in passive voice. They are the result of active policy choices. The United States is the richest country in the history of the world, with a $19.39 trillion GDP, and yet 21% of all children in this country live in poverty. We have the ability to end poverty in this country. We have the ability to end homelessness, end medical debt, end income and wealth inequality. Why do we not?

Radicalism is not an action—radicalism is a mindset. Radicalism is looking at the problems we have today, asking, “how do we fix it?” and then doing that thing. Radicalism is working off of principle, not politics. Radicalism is never compromising on values, even when it might seem politically expedient to do so. Radicalism is finding a solution that you think will work, really work, and then pushing for that—not something else, not some lesser solution that you think will get enough votes or rally more support but ends up being a watered-down lookalike of what you really believed in the first place.

This all might seem unrealistic, or naïve. I can already hear the chorus of voices saying, “That’s not how things work,” “You’ve got to be more reasonable,” or my favorite, “You’ll change your mind when you’re older.” I am baffled at the thought that some people can look at a staggering poverty rate and millions of people bankrupt from medical debt and wage stagnation and racial wealth gaps and homelessness and say, “Boy, I don’t know.” Radicalism means having the courage to stand up to paralysis and gridlock and a sterile, unimaginative political system and say, “Enough.”

These are the times that try men’s souls: the summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this time of crisis, shrink from his values and beliefs and, looking at the rot that has taken hold of this country, say, “Let’s go back to how things were before.” He will gaze upon the deepest, most gut-wrenching poverty any of us can imagine and say, “Let’s be realistic about our solutions.” He will hear the revolt of generations tossed aside and buried by a broken system and say, “Slow down.” Historical moments such as these often come but once in a lifetime. The question I pose to these moderates is this: will you meet the moment, or will you fall short?