According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation: Criminal Justice Information Services Division, there has been a sharp increase in hate crime in the United States since 2016, though the most current data published by CJIS details events from 2018. Not included among the ongoing tally of hate and bias crimes in the United States, however, is the far more prolific problem of hate speech. This magazine has previously chronicled examples of hate speech on the campus of Portland State University and throughout the Portland metropolitan area.

Hate speech currently lacks a legal definition under United States law. We can propose, however, a definition based on Kenneth Ward’s 1998 contribution to the University of Miami Law Review in an essay titled “Free Speech and the Development of Liberal Virtues: An Examination of the Controversies Involving Flag-Burning and Hate Speech.” In this essay, Ward describes hate speech as “any form of expression through which speakers primarily intend to vilify, humiliate, or incite hatred against their targets.” Such targets would then be grouped according to the conventional enumerated grounds of “race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender, or gender identity,” and the implied grounds that accompany them in line with the FBI’s definition of a hate crime.

I would like to believe that the need for competent hate speech law is evident, as the connection between hate speech and the commission of hate crimes is self-evident, but the United States as a country seems to disagree.

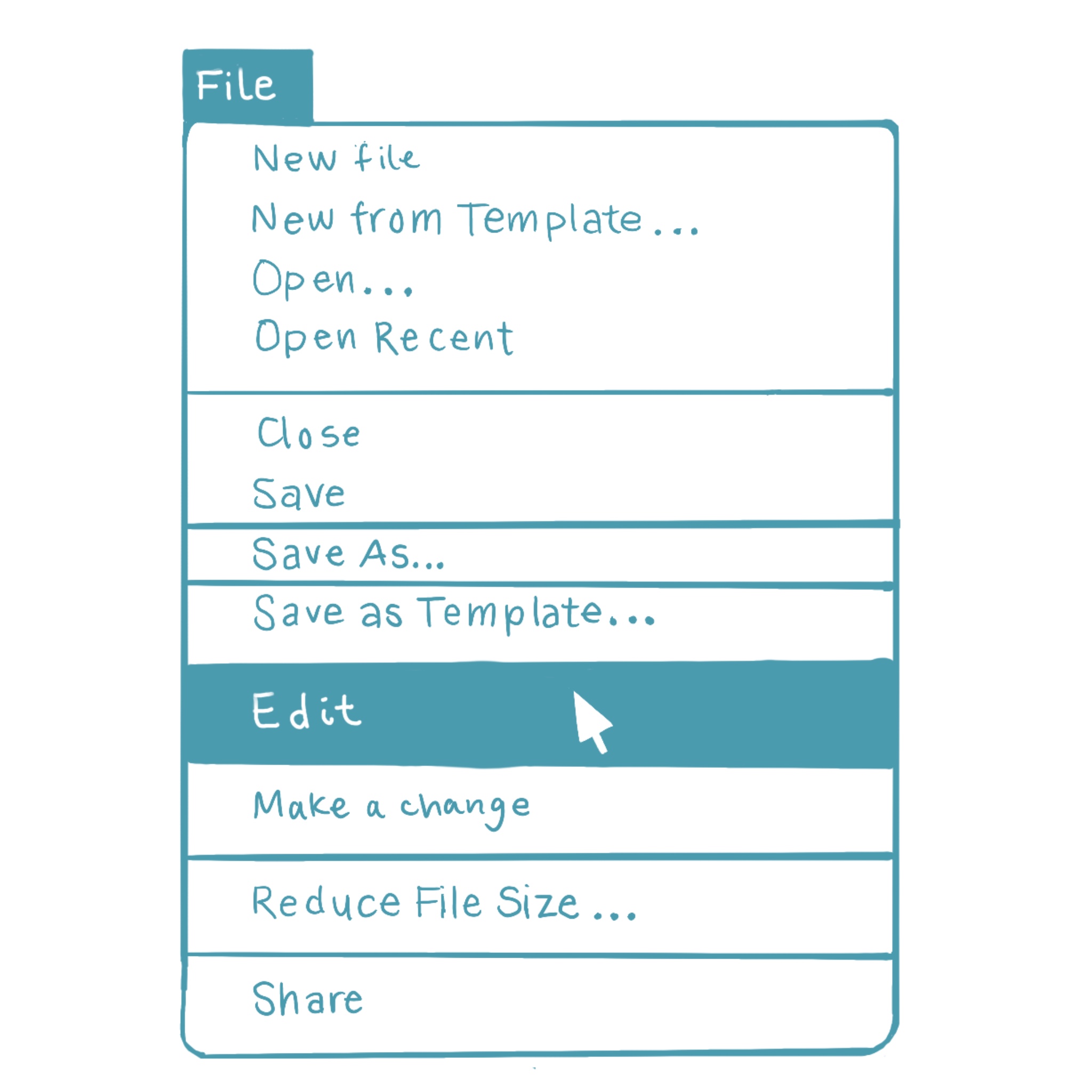

illustrations by Alison White

I’ll base my assessment of hate speech law in the United States on the case of Matal v. Tam, which was decided by the Supreme Court in 2017, and the precedent that informed it. In this case, the Supreme Court unanimously decided that not only is hate speech protected by the First Amendment, but many laws and policies to prevent it may be unconstitutional. The bulk of the case revolved around the use of a “disparagement clause” in patent and trademark law. This disparagement clause essentially prohibited the registration of trademarks that disparage the members of a racial or ethnic group, or any other group that can be read into the law. According to Justice Samuel Alito’s opinion, “Speech may not be banned on the ground that it expresses ideas that offend.” The disparagement clause was deemed unconstitutional and a precedent was set with the justification from Alito that “the proudest boast of our free speech jurisprudence is that we protect the freedom to express ‘the thought that we hate,’” himself ending with a quote from Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in United States v. Schwimmer. I respectfully disagree with the assertion that hate speech merely offends, and I assert that hate speech becomes so when it can be construed as a call to action, vilification, or humiliation that harms a protected class of people. Though I would agree that the example in Matal v. Tam qualifies as reclamation of a slur, rather than hate speech, it is the precedent made by the wording of the judgement and its grouping together of hate speech and offensive speech that raises concern.

The precedent from Matal v. Tam establishes a rather frightening proposition that any attempt to curb hate speech on the part of state governments may be unconstitutional. There is, however, a minor saving grace. The Brandenburg Test, established by the Supreme Court case Brandenburg v. Ohio in 1969, is a legal test that determines which hate speech may not be protected by the First Amendment. It is a two part test that requires the hate speech to both be “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action” and be “likely to incite or produce such action.” Essentially, that means that hate speech must compel an illegal act and be likely understood by the listener to compel actually committing that act. This puts the state of hate speech law in the United States roughly on par with the law concerning threats of violence or property damage. That is to say, it is largely ineffective until a hate crime is either committed or conspired.

Knowing this about American law in the present, how can we create more responsible hate speech law in the future? There are multiple models in existence elsewhere in the world. Germany, for example, has explicit hate speech law written into their criminal code. New Zealand has embedded hate speech law into their national Human Rights Act. The United Kingdom has its Public Order Act and numerous legislation that has expanded it. What none of these nations have, however, is free speech protection that has been interpreted to protect hate speech and prevent countermeasures in the first place. For an example that better fits the situation of the United States, we should look to Canada and its Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms is similar to the Bill of Rights in the United States, and has the same authority as the Canadian Constitution. Indeed, it even starts in a similar fashion to the United States Bill of Rights, with its section two guaranteeing “freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication,” as well as religious freedom, freedom of peaceful assembly, and freedom of association. The major difference between the freedom of speech protections in the Charter versus the Bill of Rights is what is written in section one of the Charter. Section one reads:

“The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.”

That’s where hate speech law is saved. I won’t go into the legal reasoning in Canada, but this single sentence empowers Provinces, Territories, and the federal government of Canada to create reasonable hate speech laws that do not violate the Charter. If the laws are too strict, they can be struck down by the Supreme Court of Canada and made more lenient, which prevents the abhorrent possibility of a government cracking down on opposition speech. It’s an ingeniously simple principle of Canadian law that essentially pushes the responsibility of determining what is and is not acceptable speech to the courts, which are then bound to their precedent to protect existing rights.

What I’m proposing is something similar in the United States, an amendment to the Bill of Rights that would grant the power to create reasonable laws to curtail hate speech, which would then refer the validity of those laws to the courts. One sentence can save us from the quagmire currently surrounding the generation of hate speech law, which would put us more in line with our economic contemporaries like the United Kingdom and Germany. As we have seen from Donald Trump’s disparaging remarks toward minority groups and the coinciding rise in hate crimes since 2016, there is a need to curb speech that vilifies, humiliates, and leaves already vulnerable groups susceptible to greater harm. If American society is not prepared to defend its vulnerable by moral strength alone, it is up to its people to empower the law to intervene.