illustrations by Bailey Granquist

When the sun rose in January 1920, it rose, as it always does, on New Zealand.

The crimson warmth of a new decade shimmered in the waters of the Southern Hemisphere before slowly making landfall. Idyllic coastal shoreline gave way to forest, then outposts, the sun at last illuminating the roads and cities of the grand imperial civilization. It would have reflected off the polished wheels of new industry, the cars and airplanes brought in across the British commonwealth. The sun of 1920 would have shown on factories and coal ships, and on new paved roads. But mostly, as the decade dawned in New Zealand, the sun bathed freshly dug graves.

In the first days of January 1920, the island nation was dying. The influenza pandemic that had spread across the globe reached New Zealand at around the same time as the first bodies came back from the war.

Two gruesome tragedies of the 1910s had devastated the country. 18,000 soldiers had died in the First World War, and another 40,000 were wounded. Many suffered brutal deaths in the failed attack on Gallipoli. The disease that struck shortly afterward—an influenza epidemic colloquially known as the Spanish flu—killed another 9,000 people. Over half the population was affected by one or the other calamity.

The rising sun continued its path, passing the burgeoning imperial Japan to which it would one day give a name and a flag; over Soviet Russia, where the tumult of revolution had finally landed Vladimir Lenin in power; and over the fields of Europe, where carefully dug trench lines still pock-marked the earth.

The new decade heralded an era of peace and astounding prosperity. Industry would advance to unimagined heights. Unrestrained capital would expand endlessly, monopolizing whole sectors of life, producing inconceivable profit and driving the colonization and exploitation of every corner of the globe. It was to be a time of radicalism and revolutionary spirit, where technology and science would spread, for the first time, a world culture across a shattered society.

As the sunlight passed across England and the Atlantic it washed over hideous starvation and poverty. Slums filled with vagrants and streets of beggars. Hospitals crowded with the sick and dying, gutters clogged with bile and mud, ghettos of the poor and disenfranchised alongside gilded towers of excess and wealth.

It would have lit the Potomac River and the White House, where the feeble and partially paralyzed President Woodrow Wilson held increasingly delusional visions of a recovery from his stroke and a third term in office, and passed over the senate building where Warren Harding laid the foundations for a victorious campaign, pledging a return to normalcy from the radicalism and divisions of the past 20 years.

After it had swept across all the Eastern seaboard, the American sunrise fell on its last great political player: An inmate in the Atlanta federal penitentiary.

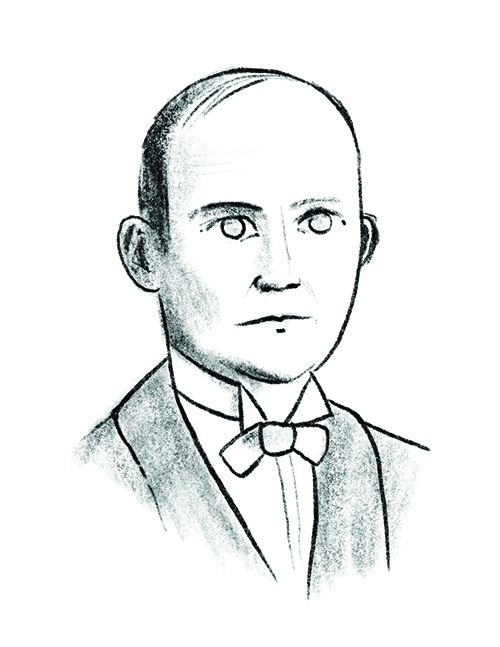

Exactly 100 years ago, Eugene Victor Debs ran the last of his campaigns for president as a socialist. He did it from jail.

When he began his career, Debs was moderate union organizer. But he was radicalized after watching striking workers attacked by police and became convinced that workers needed to organize across entire industries, not just in small trades.

Debs’s strategy proved right. The American Railway Union he organized quickly won impressive victories. In 1894, they organized a massive strike that paralyzed the nation’s rail system, protesting wage cuts and rent raises in company towns. In response, the U.S. military was called in to break the strike. They killed 30 striking workers, and injured another 50, before arresting the strike leaders.

If Debs had harbored any illusions of the possibility of cooperation between workers and bosses, they were destroyed that day. He would later write, “In the gleam of every bayonet and the flash of every rifle the class struggle was revealed.”

Sitting in that jail cell, in 1894, something happened to Debs. Something that would set him on the path to become one of the defining figures of the next few decades. Something that would convince millions to follow him and fight alongside him and, eventually, something that would land him back in jail again in 1920. Because while he was in jail, in 1894, Debs was visited by an Austrian immigrant named Victor Berger, who gave him a copy of Capital, by Karl Marx.

A century on from the terror and tumult of the 1920s, American socialism is on the rise again.

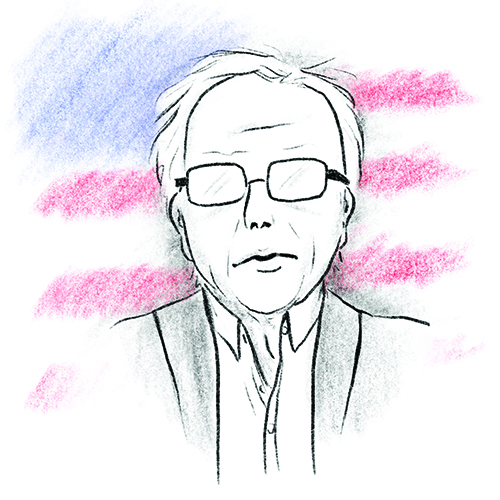

Far from a trade unionist or jailed activist, Bernie Sanders is the unlikely face of a political movement powered mostly by people 50 and 60 years his junior.

And yet, since the end of the Obama presidency, the Senator has become one of the dominant figures of the political scene. With unshakable consistency, the septuagenarian has railed against inequality and poverty. To party power brokers, his 2016 primary challenge was just a speed bump on the predictable road to President Hillary Clinton.

But against all odds and expectations, Sanders found a base of support. Decrying billionaires and bankers, his thick Brooklyn accent and unkempt hair became iconic symbols and his curmudgeonly demeanor tapped into an anger in the electorate.

His base was shockingly versatile, winning over 10 million votes and 23 states. But Sanders’s message truly found a home with young voters. He has consistently led in approval ratings with people under 35, even as he has struggled with others.

The son of Polish immigrants, Sanders’s early life was in many ways unrecognizable to the people who would one day support him. Growing up in rent-controlled housing in the post-war boom years, Sanders’s upbringing bridged the divide between Jewish radical tradition and a discomfort with organized religion. Like Debs, Sanders came of age in a time of conflict, joining the civil rights movement. After graduating from the University of Chicago, Sanders moved to Vermont, where he ran fringe third party campaigns in senatorial and gubernatorial races. Running on radical platforms, branding himself a Democratic Socialist, by all political wisdom Sanders should have stayed just that, a fringe radical. Instead, his message found a home in Burlington, where he narrowly won a mayoral campaign that kickstarted his career. It may have been a surprise to establishment media, but perhaps not for Sanders. After all, Sanders had produced a documentary on Eugene Debs. The two, as well as socialists across the centuries, recognized the existence of a winning coalition of workers, radicals, and the disenfranchised. They believed that, if all people could just be convinced to fight for one another, they could transform the world.

To understand how exactly this process has happened, and what we are to make of it, it’s important to understand just what is meant when the term socialism is used. For our purposes, the concept can be kept relatively simple. Socialism is a form of economic organization where the “means of production” (the resources you use to make a product; factories, nails, conveyor belts, wood, etc.) are controlled by the workers.

This core definition is about the only thing all socialists agree on. Who the workers are, how they are to seize control of the means of production, and what they should do once they have them are matters of great internal debate. But the vast majority of socialists broadly agree with the argument of Karl Marx that society is divided into economic classes, the two key groups of which are the bourgeoisie, who own the means of production, and the proletariat, who provide the labor necessary to actually produce.

To that end, most socialists advocate for unions—organizations where workers in a trade or industry come together to collectively bargain. While an individual worker has almost no leverage, when all workers in a factory come together and say they will strike until they receive fairer treatment, they can force the bosses hand.

Not all union members are socialists. In fact, in the 1950s, almost all socialists and communists were purged from unions. Socialists don’t just advocate that workers in a single industry demand higher pay. They say that all workers should join together to take on the ruling class. Socialists and communists have historically been the most radical labour organizers, the most willing to call for strikes and take on bosses, the most willing to use drastic tactics to force the company’s hand, and the most determined to form unions in industries that don’t currently have them.

In 1920, millions across the world were sold on the visions of socialists, be they Debs or Lenin, by the horrors of war and poverty. While the elite leaders of society hoarded ever greater profits, the working class was mired in poverty, sacrificed in war and brutalized by imperial ventures. In 2020, capitalism again seems to be failing. College has become less and less affordable, even as it is more necessary than ever. For two decades, America has waged imperial wars in the Middle East, costing trillions of dollars and sacrificing thousands of soldiers for a cause that has done nothing but destabilize the region and kill millions of Iraqis and Afghans. Healthcare costs continue to rise, as insurance premiums leave thousands uncared for. And yet even as American life expectancy declines, corporate profits soar. Arms manufacturers and health care conglomerates make millions off the suffering of the masses.

Bernie Sanders is not a revolutionary. He does not promise to overthrow capitalism like Debs once did. But he is well and truly a socialist. Borne of the working class and with a dream forged in the fire of mass discontent, with a vision of an egalitarian America where everyone has a say in government, and we all fight to take care of one another.

The dream of the socialist was always a leap of faith. It was that faith that preserved the movement through the long dark years of red scares and right wing governments. A faith in an equal society, where people of all genders and races share in the prosperity of our country. Faith in mass movements, in the power of the working class to overwhelm the barriers before them and seize power from the idle rich who control their lives. Faith in the ideal that all our struggles are shared, that we are the collective victims of a single grave crime of exploitation and that it can be overcome only through cooperation.

One hundred years ago, Eugene Debs tried to stop the most horrible war the world had ever seen up to that point: World War I. For the crime of speaking out against it he was jailed. At his trial, where he was to be sentenced, he was permitted to give a closing statement to the jury.

“Your Honor,” Debs said, “I ask no mercy and I plead for no immunity. I realize that finally the right must prevail. I never so clearly comprehended as now the great struggle between the powers of greed and exploitation on the one hand and upon the other the rising hosts of industrial freedom and social justice.

“I can see the dawn of the better day for humanity. The people are awakening. In due time they will and must come to their own.”

No one can say if Sanders will win the primary—he currently sits in a dead heat with Joe Biden. Whether he will then manage to implement his ideas is an even harder question. But it seems doubtful the story of American socialism will end with him. Wherever there is an oppressed class, there is a voice for radical change.

And though the dawn of this new decade brings with it great fears and horrors, in the fires of war and floods of climate change it brings with it something of Debs vision as well. In the rise of mass movements which extend far beyond and will last far after the campaign of Bernie Sanders, there is an awakening of the vast working class. People are coming to believe at last, that in this age of unparalleled prosperity, we can build a kinder and more caring world. One where everyone gets the things which they are owed.

Debs and Sanders are divided by years and values, party and place. But they share one single, towering belief. That political change cannot ever come from above. That if the world is to be remade, it cannot be by a single candidate. That responsibility rests with all of us.