This piece was cowritten by Sarah Samms & Jeremiah Hayden

On a recent Wednesday afternoon, a diverse group of students and faculty stood quietly by, at first, as a small group of anti-trans activists held cameras and provocative signs in PSU’s Urban Plaza. One provocateur, a tall, slender man with a bicced head and a cleanly shaven face, had a billboard strapped over his pink shirt and gray blazer jacket that read “Children Cannot Consent to Puberty Blockers.” The man, an internet personality with a modest following, shares a similar ideology to other disingenuous right wing grifters—his Twitter header is a screenshot of himself as a guest on a former Fox News show.

The anti-trans group attempted to goad students into a discussion by making controversial statements, and a few responded by yelling and throwing water into the scrum. One at a time, some onlookers engaged their argument in an effort to reason with the group, while others made noise, shook tambourines, laughed, led chants, and walked slowly into the group to push them out of the square.

A palpable tension hung in the air as the group’s two personal security guards stood nearby. They moved with the crowd and kept a close eye on the periphery, as if some unexpected thing could happen at a given moment. Standing back from the crowd, three PSU Campus Public Safety officers (CPSO) flanked the east and northwest corners of the square, guns holstered on their hips.

The scene illustrates some of the dynamics at play as PSU tries to thread a needle with regard to campus safety. On the one hand, a diverse student body should be protected from those who want to turn joy into a negative spectacle. On the other hand, many queer people, people in poverty, people of color, with disabilities, those with mental health or addiction struggles, and those trying to survive a difficult world in the shadow of a global pandemic don’t find safety in the presence of yet another gun.

How did we get to where we are today? How can we imagine a future in which everyone, including those most impacted by paternalistic security practices, feels safe as we move about our city?

The process to create an armed and deputized police force—now known as Campus Public Safety Office (CPSO)—began in 2008 with a report by the office of the Vice President for Finance and Administration, and the PSU Board of Trustees voted it through on December 11, 2014. Since then, student activists have raised the alarm over fears that a heavy police presence on campus does not make people safer, and could in fact endanger the very people they are sworn to protect.

“We occupied! Every board meeting! Last year! We begged, we pleaded, we told the administration, Black Lives Matter,” PSU Student Union activists chanted as they disrupted the President’s speech at Vikings Day in Fall 2015. That same year, they organized sit-ins at two Board of Trustees meetings.

In 2016, PSU Student Union and Disarm PSU member Olivia Pace argued at a forum that dissenting voices had been ignored during the process to arm CPSO.

“That is not a safe campus, when those being kept safe aren’t included in those decisions,” Pace said.

On May 10, 2016, Disarm PSU organized a walkout of 500 students, and a confrontation and racist chant by Trump supporters at the rally highlighted what is at stake for the PSU community.

On June 29, 2018, activist’s fears became a reality. Jason Washington, a 45-year-old postal worker, Black veteran, registered and licensed gun owner, was outside of the Cheerful Tortoise, just a few blocks from the campus square. According to reporting from The Oregonian at the time, Washington was carrying a gun for his friend, Jeremy Wilkinson, to “prevent him from making a ‘poor decision.’” A fight broke out outside of the bar, and Washington jumped in to de-escalate the situation. Two CPSO officers, James Dewey and Shawn Mckenzie responded to a call regarding the fight. When they arrived, Washington was retrieving the weapon that had fallen onto the ground. According to the body cam footage reviewed by OPB, the two white officers yelled “drop your gun” at Washington, just one second before opening fire. Officers fired seventeen rounds in fifteen seconds. Washington was struck nine times in his back, in his side, and in his leg, with one bullet grazing his cheek. He was pronounced dead at the scene. He left behind a wife, three daughters, and a granddaughter.

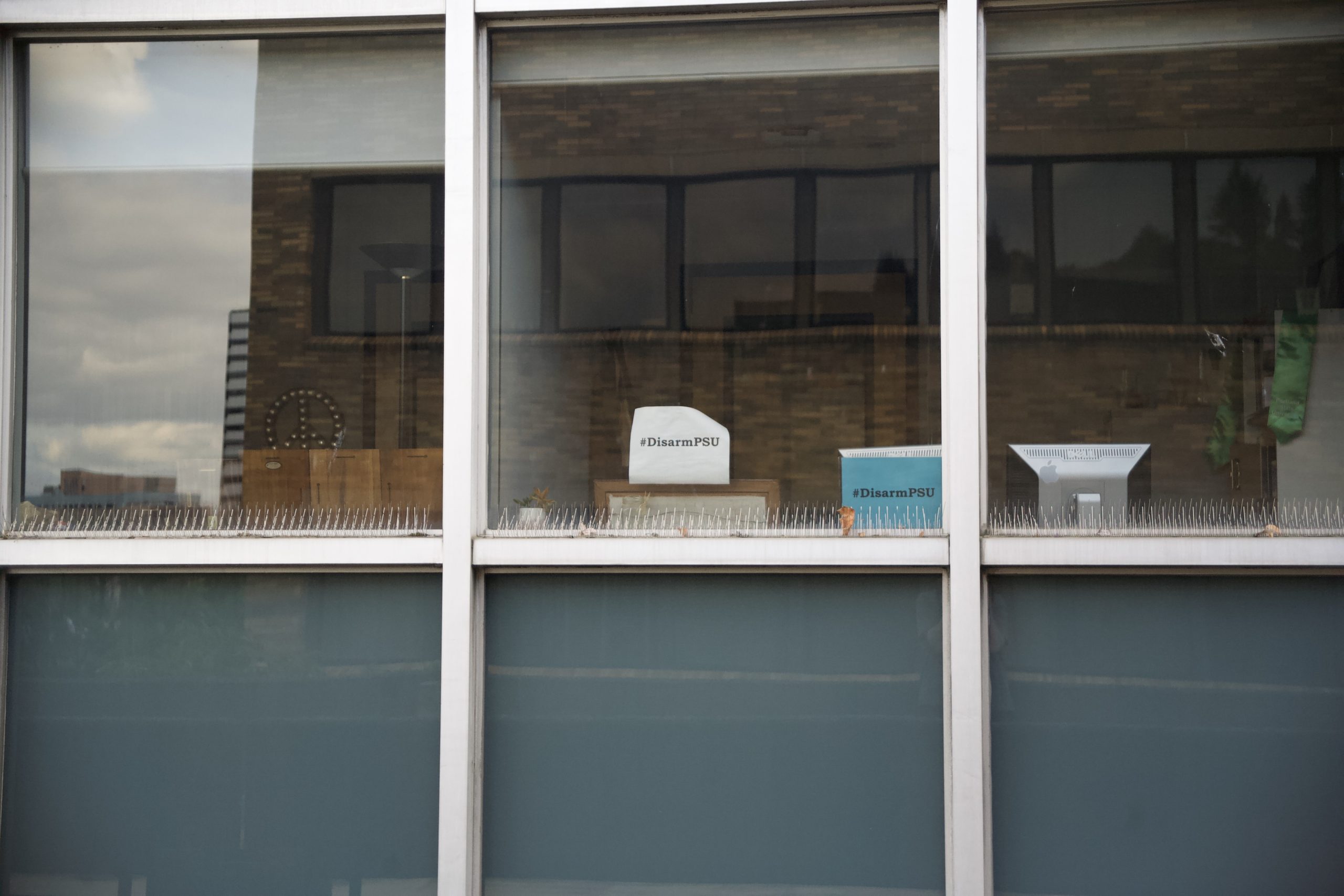

The community was outraged, and responded by occupying the outside quarters of the CPSO building on the PSU campus for ten consecutive days in September of 2018.

Despite Washington’s death, and the concerted efforts of the community, the students, and the newly-formed coalition Disarm PSU, CPSO was not effectively disarmed until after the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020 and the uprising that proliferated in response to the long history of systemic racism and white supremacy embedded in that egregious act.

In August 2020, PSU announced its decision to “reimagine campus safety,” saying they would be “disarming CPSO.”

Within the institution, multiple committees function to create university safety policy. University Public Safety Oversight Committee (UPSOC) is composed of students, alumni, faculty, staff, and community members who are appointed by the PSU Board of Trustees to provide oversight, counsel, and advice on campus safety. Reimagining Campus Safety Committee (RCSC) was started during President Stephen Percy’s tenure, and according to their website, that committee of similar stakeholders “functioned in a time-limited manner to develop a set of recommendations to improve campus safety.”

In the RCSC final report submitted to President Percy in Fall 2021, the fine print stated that “CPSO should prioritize unarmed responses and create alternative responses to low threat level calls on campus.” But despite the August announcement that CPSO would be disarmed, they never entirely did so—the policy itself never fully committed them to unarmed patrols, and the communication surrounding armed and unarmed patrols has been scattershot.

“There’s provisions in that policy that says upon the chief’s discretion, that I can, for operational purposes, have officers patrol unarmed,” CPSO Chief Willie Halliburton says. “Within policy, you have to have two sworn officers to be unarmed. So those are minor deviations. It’s my fault. I take credit for that. I did not communicate those changes.”

President Percy acknowledges that communication needs to improve, as it has further entrenched mistrust between activists for disarmament and the university.

“We always felt we were consistent with the policy. But the practice within that policy was changing enough that I said at that time that I wanted to consult with UPSOC. We need to do a better job of communicating to people, and that’s something I am committed to.”

In their report, RCSC made 36 recommendations to his office, and Percy says PSU is moving forward on all of them.

“I think we have transformed the culture in our CPSO team,” he says. “Job done? No. Making progress? I hope so. Others can judge for me.”

Campus Police Chief Willie Halliburton says he had never touched a gun until he became a police officer 34 years ago. Hired by Portland Police Bureau (PPB) in 1990, he worked in various patrol and assignment roles before joining PSU in 2016. Halliburton speaks softly and earnestly when he talks with students about his vision of public safety, and he seems to believe deeply in America’s police as a force for good, despite what he calls “a few bad apples in a noble profession.” He gets emotional when he talks about his officers. “They’re my heroes,” he says.

The week after PSU President Stephen Percy notified students that CPSO would resume armed patrols on campus, some 40 people packed into Smith Memorial Student Union for Coffee with the Chief. Halliburton sees the town hall style meetings with students and faculty as an opportunity to engage and rebuild trust between campus police and the academic community. With CPSO resuming armed patrols nearly two months before he and Percy told students, rebuilding trust is a tall task.

“Back in 2020, I said I needed to earn your trust,” he says. “Now that I got your trust, I don’t want to break it. Trust is easily broken, believe me. I don’t want that to happen.”

Halliburton remembers when he and Percy announced the discontinuation of armed patrols in 2020, as racial justice protests helped amplify demands for new approaches to community safety. After years of work from the PSU community, Halliburton remembers it as a moment in which PSU was ready for change.

“We were hurting as a community,” he says. “The United States of America was hurting. I made the announcement that we’re gonna be the first police department in this country to do our job without weapons.”

Halliburton says he wanted to create a “new police officer” at that time, who didn’t need a weapon to “be who we are,” or to be “bold,” or “macho.” He wanted police officers who can relate to people. “It was a mindset that killed George Floyd,” Chief Halliburton says. “No weapon was involved. We have to have a different mindset.”

Halliburton is not shy in sharing anecdotes about life on the job to justify rearming CPSO. He tells short stories of people with hatchets and guns, car break-ins, drugs, houselessness, and a suicidal kid barricaded in a room when he was a sergeant at PPB in 2010. He says the city has changed—“homicides are climbing,” and “people are trying to survive, but unfortunately some of them are trying to survive in a negative way”—and he blames 2020 protests and riots for PPB staff shortages that they say make it harder to respond when CPSO calls for backup.

“I’m really tired of white America telling me that guns always fix the problems,” a disgruntled PSU student in a Disarm PSU Coalition meeting said. Guns are on everyone’s minds here in the U.S. They’re displayed across the media everyday, whether we’re forced to see another mass shooting by a person armed with an assault rifle or someone else murdered by a police officer. So far this year, there have been more mass shootings in the US than there are days. Are guns the problem?

Like Minneapolis, Denver, Milwaukie, and other cities across America, local students at Portland Public Schools (PPS) joined a nationwide movement calling for the removal of School Resource Officers (SRO) from schools because of biases and abuse toward children of color. In one case, with a concerted student effort, Students Against Oppression (S.A.O.) forced Gresham High School to get rid of their SROs altogether, freeing the students from fear of abuse by officers.

This leads to the question: do SROs keep schools safe? And do guns keep schools safe? Or are they the problem in the first place? Jason Washington was trying to de-escalate a bad situation outside the Cheerful Tortoise that night in 2018, but the gun—in his hand and at the hands of those charged with protecting PSU—is what got him killed.

It goes to show that this is a multi-dimensional issue that takes more than one action to resolve. It takes more than just disarming CPSO, it takes proper training in de-escalation, mediation, and understanding subconscious biases so they can operate safely and fairly in a complex world.

Chief Halliburton gave CPSO officers permission to resume armed patrols on February 14, and made the decision permanent on March 9. It wasn’t until April 11 that President Percy sent an email to students to alert them of the change, stating “our officers are encountering an increasing number of weapons on and near campus and they are receiving limited assistance from the Portland Police Bureau due to increased demands for officers across the city.”

While PPB communications assert that calls are increasing, the statistics show that dispatched calls in Portland on the whole are down to 18,659 in March 2023 from their August 2017 peak of 24,342. (“Crime” is a malleable category of its own in police statistics, sitting beside Disorder, Traffic, Alarm, Civil, Assist, Other, and Community Policing statistics.) According to The Oregonian, PPB’s authorized police force fluctuated between 950 and 1,000 officers between 2011 and 2020. PSU research showed that the officer-to-resident ratio dropped by 22.3% in that same time period, in part due to the influx of people moving to Portland.

“Some of those calls for service that the police hear may not be crime,” Percy told The Pacific Sentinel. “But I know that there have been times when (CPSO) had been told (PPB) would come but there wouldn’t be a very timely response.”

A 2022 KPTV article amplified an unverified message from a PPB spokesperson saying there are “simply not enough police officers to serve the volume of calls.” The spokesperson is quoted saying, “we have to prioritize what we can do based on our resources. These days, we are not able to offer the kind of service people expect or that we wish we could provide.”

The Pacific Sentinel asked President Percy what specific data set he and Chief Halliburton referenced before communicating anecdotal information to the PSU mailing list.

“Their calls for service are definitely up,” he said. “I have not seen crime data specifically. I’ve read the newspapers, but I’m no expert on it.”

Asked the same question, Chief Halliburton told The Pacific Sentinel that Percy wanted him to get that information as well—“that is one of the things on my list.”

This discrepancy in statistics and verifiable information creates confusion between students and those making campus safety decisions. According to their most recent staffing report, PPB currently has 805 sworn officers. Percy says, at PSU “the number of incidents in the previous two or three years involving weapons of any kind was less than five” and that “in the last year, it’s been three or four times that.” A PSU communications director told OPB that the increase was 180%. Chief Halliburton told Disarm PSU that the number of weapons was 12.

According to research sent to The Pacific Sentinel from Skye Bailey of the PSU Sociology Club, CPSO has responded to seven incidents of assault between January to March of this year. This is roughly the same when compared to that same time period in the previous three years: 2022 (5), 2021 (1), and 2020 (6). In total, 2022 saw the highest number of CPSO responses to assault (20), compared with 11 in each of the two prior years.

Those numbers are drastically lower when looking at aggravated assault—meaning a weapon, including hammers and other non-firearms, was present. National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) data shows six instances in the past three years in which CPSO responded to aggravated assault, half of them in 2020. Detailed arrest records show a disparity in who is policed as well. While Black or African-American students make up 4.30% of the population at PSU, they make up 21.9% of all CPSO arrests in the past three years.

Recently, there has been an increase in communications from PSU to students after incidents occur on campus—a change from the previous operating procedure of only sharing if there’s an ongoing threat to the campus community. Does the desire to know justify the fear created by the alerts?

After the long and enlightening year of 2020, reformists and abolitionists have learned many things, one of them being that not everyone will agree on the right course of direct action toward police accountability. Many young people are taking their future into their own hands, equipping themselves with skills that prepare them for unexpected crises and encounters with the police.

Reverend Osagyefo Sekou, a pastor of theology & arts, offers programming to train students on “safe practices for non-violent civil disobedience.” In collaboration with the Dores Worker Solidarity Network in Nashville, Tennessee. Sekou recently trained student protestors in safe, non-violent civil disobedience practices in response to gun reform activism around the Vanderbilt campus. The training entails how activists should hold their ground during a protest, what to do if they get tear gassed, and how to protect oneself from a police baton strike.

On a DIY scale, grassroots organizations host sliding scale workshops to teach students how to safely de-escalate, mediate, intervene in a crisis; about mental health first aid, and how to physically defend yourself. Younger generations are preparing themselves for the future, rather than relying on older safety models like a police force or campus security.

“I’m sure you’ve heard the very classic statistic that pizza delivery drivers are more likely to be killed than cops,” a PSU student told Chief Halliburton at Coffee with the Chief. “All of us are really going about this world prepared for anything that’s going to happen. We are all marching through this world with the understanding that we don’t know what’s next, and we’re doing our best in it.”