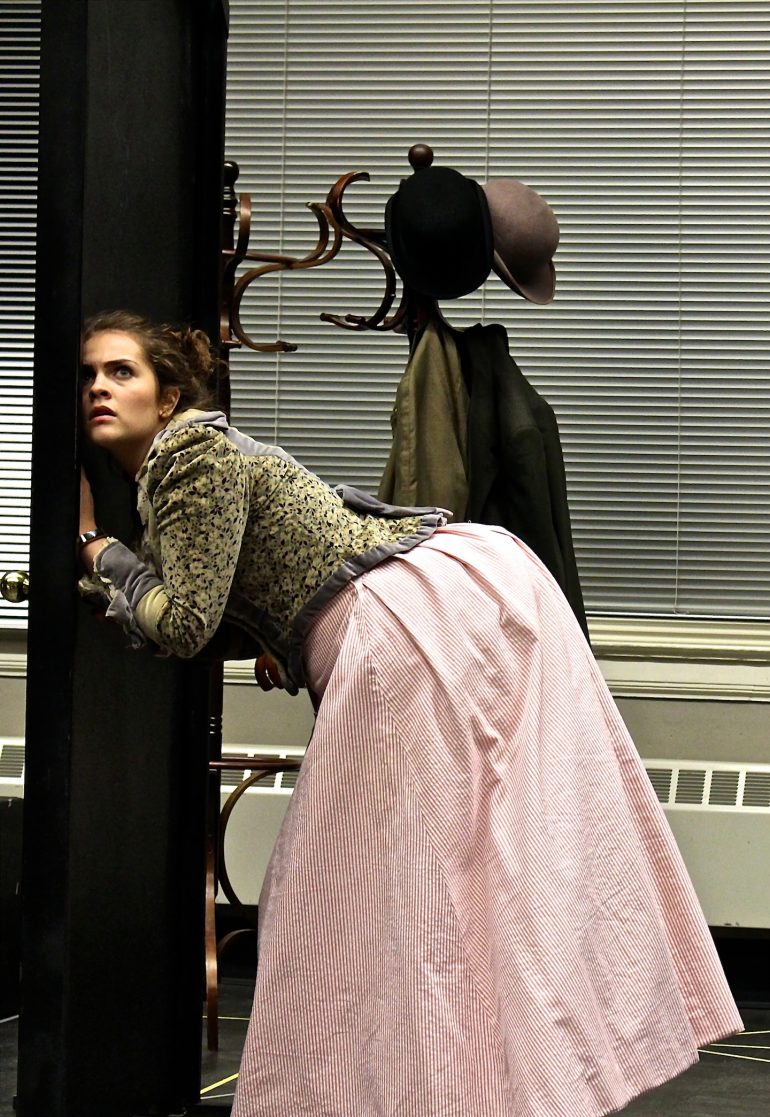

Portland State’s newest play production is In The Next Room (or The Vibrator Play), a mature comedy written by Sarah Ruhl that deals with sexuality and intimacy in the 1800s. The show surrounds the main characters Dr. Givings and his wife Catherine, as well their midwife Annie, Dr. Givings’ patient Mrs. Darcy, her husband Mr. Darcy, a wet nurse Elizabeth, and a male patient named Leo Irving. Dr. Givings runs a medical treatment for hysteria in his home office, a room blocked off from the rest of his house. This play takes place during a time when electricity is still new and of fascination to all the characters.

Electricity is of special interest to Dr. Givings, who uses it to power vibrators as a way to treat hysteria in his patients by giving them paroxysms, doing so with the help of his midwife Annie. The play starts out with Mr. and Mrs. Darcy coming to Dr. Givings to help the highly anxious Mrs. Darcy’s health. The show moves forward as these characters slowly become intertwined in one another’s lives in unexpected ways. Barriers are broken down, and they learn about themselves and others in their most vulnerable state.

This is a play about sex and female sexual awakening, but ultimately it’s a story of how love is expressed to others and what kind of relationships these people deserve. The characters challenge each other and learn things about themselves while doing so; the show ultimately concludes leaving the audience with a message of love, heartbreak, and the nature of intimacy.

In The Next Room runs between March 1st and 9th in Lincoln Performance Hall. I spoke to five members of the cast and crew about the play itself and their roles in the upcoming production.

The following interviews have been edited for clarity and brevity.

Jon Davis: Mr. Daldry

Brooke Jones: How did you approach this character as an actor/how did you prepare for this role?

Jon Davis: It’s interesting playing a man in this age, because the idea of being a man was so different. And even just the way this guy talks to his wife is just very uncomfortable for me. I mean, it’s been hard, it really has. I try to remind myself that these men aren’t, like, malicious in the way that they’re a little sexist. They do love their wives, they’re just playing the roles that they were told to play at that time. So, in preparing for the character, I try to focus on other aspects of his personality. I had to decide what life he brings to the play because all of these characters are so full of life. It’s interesting how these characters are so reserved, especially in the first act, but as the play goes on you see them open up and the way they just have so much energy and life inside of them.

Preparation wise, I chose to read an entire etiquette handbook from 1886. It’s kind of crazy. There’s a lot of stuff I would not have imagined. The etiquette for attending a dinner party was an entire chapter. I don’t think of that nowadays. The way they viewed life was very carefully. They had a lot of rules, because I think that’s the way they enjoyed life, which sounds so crazy to us now. But I think the idea of having these social rules was very comforting for these people.

Ruhl’s explorations of sex in this play are closely related to gender roles during this time period. How does Mr. Daldry break or enforce these gender roles on his wife, on others, or in the story in general throughout the play?

JD: I really hesitate to say that I enforce them on my wife… but there are ways that I have that subtle patriarchy come out. She’s at first afraid to go to the doctor’s office and I tell her to “be a good girl”…yikes. It’s pretty subtle, and I think the playwright purposefully keeps it to just few things. I think she really doesn’t want this to be a play about roles between the sexes, as specifically in marriage. I think she touches on that quite a bit because it’s very important for us to see why the doctor and his wife have this disconnect, but I don’t think she’s necessarily critiquing those roles as much as she’s saying…that they can break free of those roles and still be people of that time.

Madeleine Peterson: Annie

How did you approach this character as an actor, and how did you prepare for this role?

Madeleine Peterson: It was kind of tough, this character, just because this character has the least amount of lines and the least amount of information, so there are a lot of liberties I could take with it personally. She is very put together and into her routine. She’s a lot older than I am, so that’s been interesting. In the show, toward the end she comes to the realization she’s a lesbian so that’s fun and interesting [laughs]. I’m trying my best to understand that journey. I’ve been talking to people, because I don’t want to portray that incorrectly, I would want to do my best to do it liberty and do it justice.

I’ve been doing a lot of dramaturgy [background research]. It is kind of tough to find stuff about that specifically in the 1800s. It’s a very different time period. [laughs] It’s definitely different than 2018. I had to do research on women’s education at the time. I believe Annie went to school. Some women who went to school and didn’t end up getting married: they would get jobs. I had to pull what I could from my dramaturgy and what little hints are given [in the script] and build something around that.

One of the main themes of the play is female sexual awakening. What role does your character play in this plot?

MP: Mrs. Daldry, as she is being treated for hysteria and she’s discovering herself sexually and all that stuff—I am very much there as a part of that journey. I use the instrument on her and help her “paroxysize” [laughs]. It’s called a paroxysm in the show. There’s that and also, much smaller, but you know, my character is coming to terms with—you know she’s never been interested in sex or men until she realized, “Oh shit, that’s why, it’s because I don’t like guys!” [laugh]

(Spoilers in this question!)

What is the significance of the moment when Annie and Mrs. Daldry kiss? Why are they both confused after the kiss, despite having moments that lead up to that particular one? When Annie leaves the stage after Mrs. Daldry says she had better not see Annie again, upset, how does this conclude her arc as a character?

MP: It’s interesting. First seeing Annie, you sort of just think she’s like an onstage crew member; she’s just, like, doing stuff and not really important. But then she ends up having this really important arc with Mrs. Daldry and everything. Throughout the play, all the characters fall off the wagon a bit, everything gets chaotic. Then at the end she realizes there is more to life than just her job. She could be interested in that sort of relationship with someone, but also who knows if that could even happen for her at that time? I think she’s going to evolve as a person past what we see of her. She’s not going to be living the exact same life that she was before.”

Ethan Cockrill: Dr. Givings

One of the main themes of the play is female sexual awakening. What role does your character play in this plot?

Ethan Cockrill: In the play, my character invented this vibrator. It’s a very complex thing. There’s a downplaying of the sexual aspect of using the vibrator in this manner. It seems the male characters such as myself know that the paroxysms are sexual in nature. I think I play the part of love and caring, but [my character’s wife and I] definitely don’t have a relationship like the Daldry’s do.

I’m not sure he’s necessarily trying to suppress female sexuality so much as he’s trying not to relate the vibrating and the paroxysms to sexuality. I think he thinks the female orgasm is some totally separate thing to sex. He does explicitly state that he only wants to help people. That’s his whole reasoning for doing everything. When I first read [the script] I was wondering too, “Is the doctor getting something out of this?” because it’s kind of a gross thing. But then as you read it, and you find out more about the characters…the people, what they state in the script is all true. So at the end when the doctor says, “No, I only wanted to help people,” it’s believed.

Your character uses the vibrator to give his patients paroxysms (orgasms) as a way of relieving hysteria. He does so professionally, and is described as being expressionless while administering treatment. What do you think Ruhl is trying to say about the nature of intimacy in her play and about Dr. Givings through these scenes involving your character?

EC: That’s really his whole character arc is that he is warm to his patients and even to his wife, but he is detached. He uses his science and his doctor status, and he kind of hides behind all of that. Anytime he has to deal with something, he just hides behind the doctor or the science. That’s kind of his arc throughout the play: He opens up and starts to learn how to be more passionate and to let go of all that technical stuff.

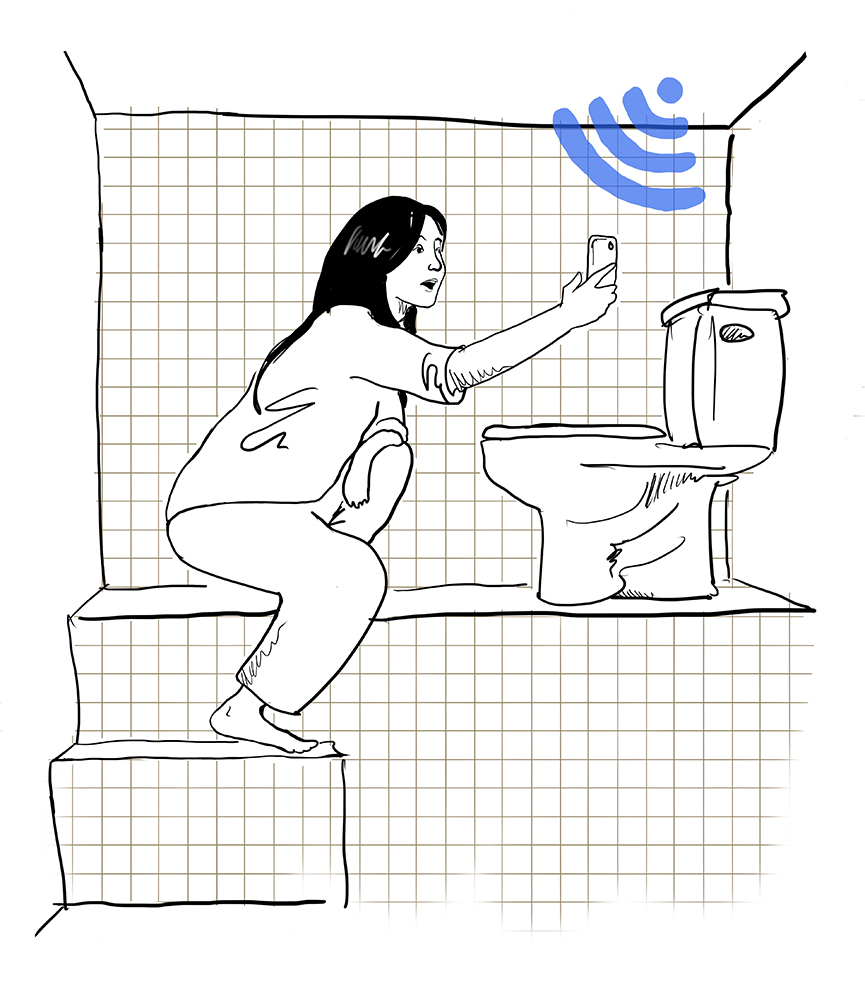

[Intimacy] is definitely a major theme in the play. I think that’s a large thing that [Ruhl] wrote, because she wrote this play in 2010. I honestly do think it has a lot to do with social media today and what we see in society now with people not being as intimate with one another. Just like, kind of the separation that humans go through and this lack of intimacy that’s there thanks to our technology. So I think that’s a large reason for her writing it.

I can kind of see that’s a large thing that’s coming through is that this vibrating instrument represents something. It’s like a barrier between [people’s] intimacy. It creates this wall, just like the wall in the middle of our [characters] house that separates people. And only when we can break through that and truly be intimate and in love with each other.

Kati Dery and Akitora Ishii: Two of the Assistant Directors

What are your duties as assistant directors?

Kati Dery: I’ve been put in charge of keeping track of all the costume changes that happen on stage, because there’s a lot [of] dressing and undressing for the parts that happen in the next room. And [the director] Devon had heard about me plotting out my own cups during Victims of Duty when I was in that, and she was like, “You have a math mind, you can do this!” So I’m in charge of that.

But then all the ADs [assistant directors], we kind of track everything, like we take a lot of notes in our scripts of what’s happening when and how much time we have for specific stuff. So whenever Evi, the stage manager, or Devon has a question about something, we basically know the answer to everything [laughs] We also are allowed to throw out little ideas whenever we feel, but also Devon is just such a good director that most of the time we don’t [laugh], because she knows way better than we do.

Akitora Ishii: Sometimes there’s problem solving like, “How are these actors going to juggle all these props?” So we’re just sort of additional minds and voices helping to solve problems behind the table. I’ve been holding book a lot of the time, being on book, if somebody calls “line,” that’s one of our duties and then taking line notes on those. And running lines with the actors when they’re not being needed on stage, that’s something we’ve been doing a bit of.

How as assistant directors did you help feature this in the play while also keeping in mind the current caution that surrounds sex and women today?

KD: This is something we tend to have conversations on as a full cast and crew, when certain topics come up. Like we’ve had photographers in the room, and Devon is very adamant about them not taking any pictures when the stuff in the next room is happening. So none of that is going to be put up as promotional photographs or anything.

AI: Devon was very specific about those scenes as well, and continuing to be very specific with the actors that they are very technical and very medical. The character that Sarah Ruhl has written, he is a gentleman.

KD: We have conversations about that with everybody and how the audience might react to these things, because yes, in our times, masturbation is a thing that happens and everyone knows it. And if this was happening in our time, it would be really weird, and uncomfortable and crude. But like Akitora was saying, this is a medical procedure for them. It’s not something they’re doing to gain pleasure. [This] play is really about intimacy and relationships, genuine relationships, between people.

Following the question of sex used in this play, Ruhl also connects sex to intimacy in her story. What do you think she is trying to say of sex and intimacy through characters? What is the arc of intimacy throughout the shows?

KD: I think one of the big things is communication. In this one specifically, the big rift is because Mrs. Givings doesn’t understand what Dr. Givings is doing and they don’t communicate about it enough. And it’s not until they do start communicating and really trying to understand one another that they can find the intimacy that they want. And it’s not with sex. That’s the point of the show, is that sex is not what you need to find intimacy and love between two people. There’s a huge undertone of loneliness that we’ve both gotten to see a lot of. Devon has been working really hard in the blocking and the characterization to highlight that and show that these characters, all of them, are so lonely in their own ways no matter what their life is like.

AI: Devon had sort of a breakthrough and understanding of the show when she realized it was about substitutes—and throughout the show, the vibrator being the substitute for the real thing, people being substitutes for what they’re lacking in their own relationships. And the way they get sidetracked and start to pursue those substitutes instead of getting to the real thing.