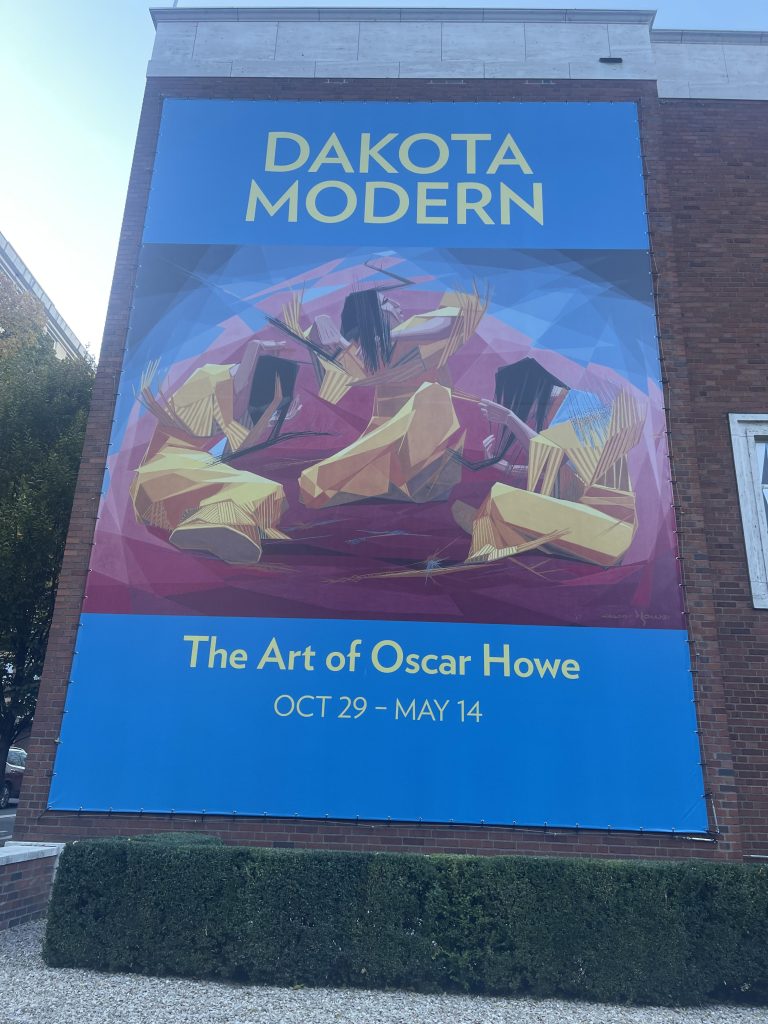

Confined inside Portland’s Art Museum, The Dakota Modern exhibit displays the work of artist Oscar Howe. As a Native American, Howe established his career through his imaginative stance on Native American culture, and breaking the boundaries tied to the art industry’s expectations of what a non-white artist should be creating.

Curated by Kathleen Ash-Milby, the exhibit twists and turns through the museum, as colors, shapes, and figures encourage the viewer to step closer. Historical prints, commentaries, and newspaper clippings accompany the artwork, giving visitors a more in-depth understanding of the artist, Oscar Howe, and the boundaries he had to break.

Graduating from Santa Fe Indian School in 1938, Howe pursued the arts, leading the way for other Native Americans to immerse into the field. His career spanned over forty years, leaving an impact on the art community and inspiring artists in present times.

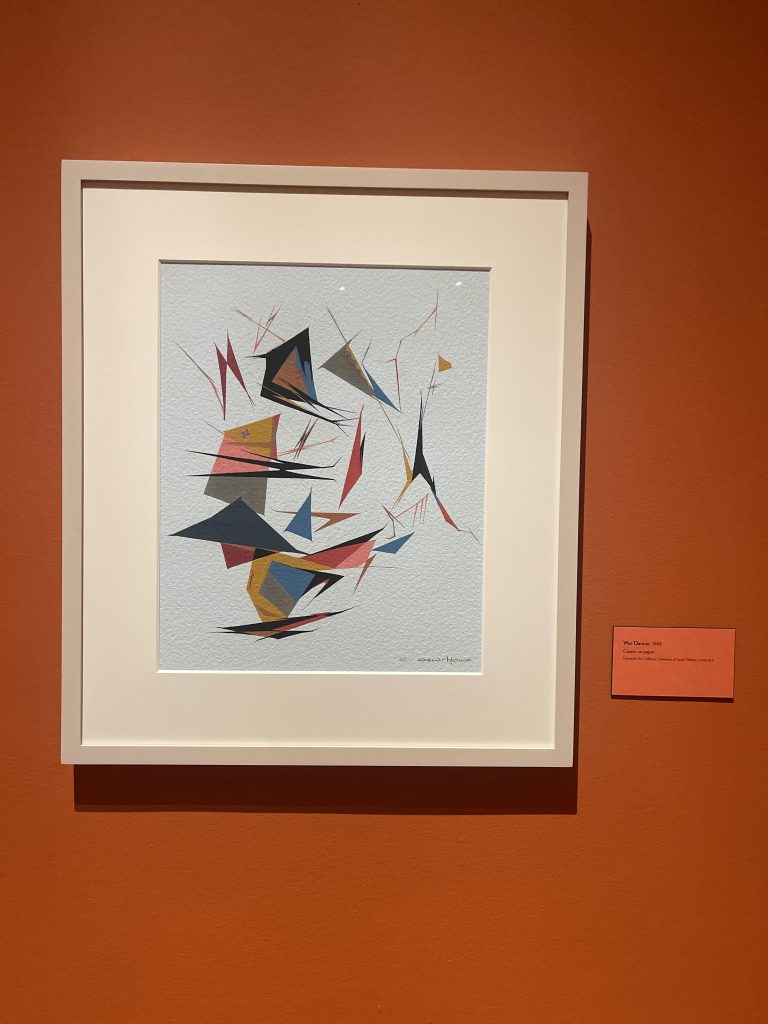

The exhibit begins with passive pieces that consist of vivid shapes and figures that echo Native American culture–scattered with more livelier paintings depicting surreal conceptions of cultural ideologies. One piece in particular, Dakota Medicine Man, painted in 1968, orients a lone figure in-between webbed lines and darker colors. Another piece, War Dancer, painted in 1968, scatters solid shapes and lines into a free flowing, yet sharp, swirl.

While the majority of his work consists of identifiable shapes and figures, his more abstract pieces of art are what garnished a push back from the overarching artistic community. In 1958, Howe was rejected from the Indian Annual Painting Exhibition, because his work was not considered “Indian” enough. Howe protested back in a public letter, rejecting the organization’s definition of what constituted as “Indian,” an micro-aggressive declaration of Native American identity.

In his response to the rejection, Howe writes, “whoever said that my paintings are not the traditional Indian style, has poor knowledge of Indian Art indeed. There is much more to Indian Art, than pretty, stylized pictures.” He goes on to say, “I only hope the Art World will not be one more contributor to holding us in chains.”

As more Native Americans heard about Oscar Howe’s rejection, they themselves pushed to break out of the claustrophobic constraints traditional American art societies boxed them into. This served as ignition for more Native Americans to revolt against the artistic community through their works.

Turning around one corner to the next, Howe’s artwork goes from neutral, passive, and cohesive, to sharp, violent, and activated. One painting, Wounded Knee Massacre, painted in 1960, displays colonizers holding weapons pointed at Native American men beneath the earth. While most of the portrait flows with neutral colors, the dark red exhibition of blood, interconnected with the stripes of the American flag in the background, strikes a harrowing tone.

A colonizer holds a pistol to the forehead of a Native American woman sitting on her knees with a baby strapped to her back. Another colonizer stabs a child to death. Children lie face down on the dirt. Bright red paint smears across the blue and beige tones, jolting viewers.

Works like these challenged the status quo of what was expected of a non-white artist. While the “Art World,” as Howe originally put it, expected to see flowy, less abrasive commentaries on Native American culture, Howe would not tolerate a confined, gaslighting filled, existence.

Although his career teetered into the abstract realm, most of his artwork depicted figures. Sometimes it’s easy to determine what these figures are, and other times it’s not; left up to the viewer to discern. However, one thing his cannon communicates to onlookers is the importance of space, and the ways in which Howe uses this space to capture meaning.

Divide and fill the space he said, the poem lingers on the wall next to another Howe painting. Written by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith in 1980, the words exquisitely capture the teachings of Howe. A line in the poem reads, “What he is saying is that the space itself is the important part of the painting. The actual drawing and coloring divides and fills the space.”

The poem ends on, “This is the Howe method of teaching.”

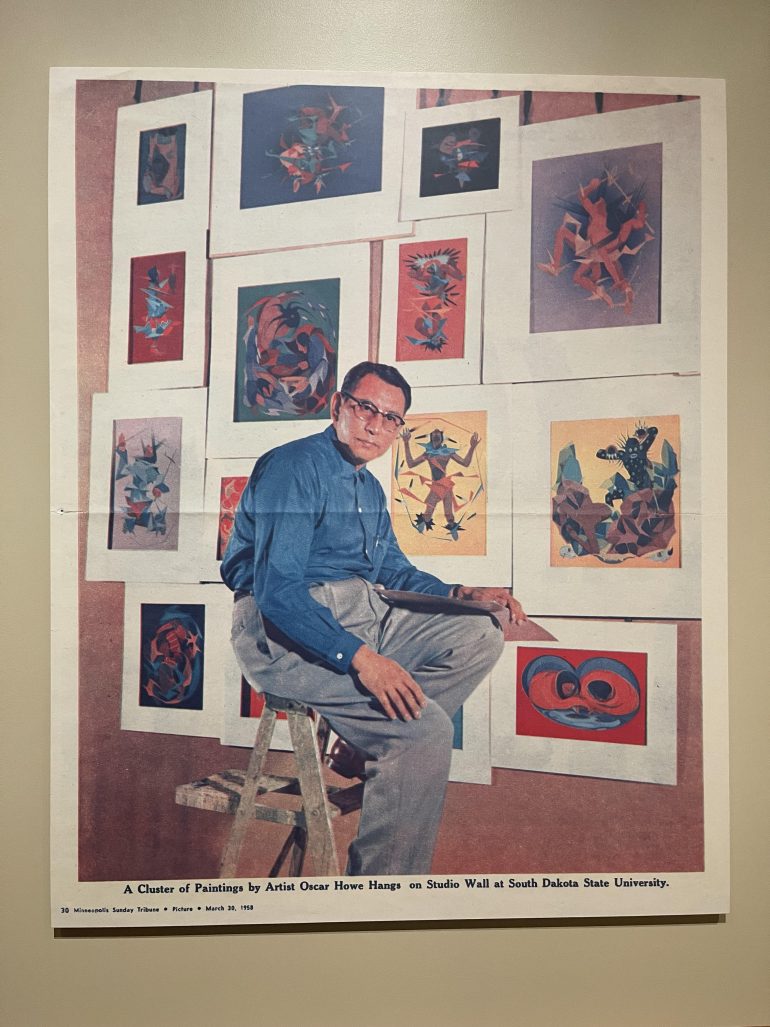

Stepping around the final corner, newspaper clippings neatly row alongside each other. Articles about his impact on the art community and photographs of him working in his studio, time capsules the entirety of his career. Lastly, there is a lone picture of a young boy standing next to an elderly Oscar Howe. They’re positioned in front of the Oscar Howe Elementary School erected in his honor.

Oscar Howe still contributes to disseminating white based artistic trends and propelling the future of non-white artists; encouraging those to break from the confines of their identities. The Dakota Modern Exhibit profoundly honors Oscar Howe’s work, encapsulating an artistic protest against the status quo and furthering his influence.