All Cops Are Bastards.

A phrase that had entered the public lexicon in 1920s England, amplified in the 1940s by working class strikes, and again in 1970, apparently brandished on a Daily Mirror headline, has once more been amplified into common usage—spray painted on walls, stitched into jackets, and even tattooed on one’s body. And the responses since have varied nearly as much as people’s interpretations of the meaning behind it. From dogmatic reverence to public outrage, one’s relationship with America’s policing institutions will often be the primary determiner of any single person’s response.

Yet, I can’t help but notice a common misunderstanding of the phrase—curated by an amalgam of outside forces, cultural competency, media representation, and personal stakes. The gritted teeth of America’s working and middle class white knuckling their thin-blue-line flags and thinking that ACAB is claiming that the cops throughout their familial line are all bad people. The common responses of not all cops and just some bad apples in the bunch.

But that’s not what the phrase is saying. The phrase isn’t “All Cops Are Bad People” but rather “All Cops Are Bastards.” Something that hints at a much larger cultural issue that requires a bit more digging than mass media channels and right wing talk show hosts can (or will) offer. It requires a look into our country’s troubled history as well as the history of policing institutions and subcultures.

+

In an article published by the NAACP on the history of police as slave patrollers, they include a sworn oath made by slave patrollers in the Carolinas which reads: “I [patroller’s name], do swear, that I will as searcher for guns, swords, and other weapons among the slaves in my district, faithfully, and as privately as I can, discharge the trust reposed in me as the law directs, to the best of my power. So help me, God.” This sworn oath is a particularly disturbing cultural artifact when considering the implications of assumed providence and the history of our country’s justice system.

They go on to explain that these slave patrollers existed until the passage of the 13th Amendment, at which time they morphed into “militia-style” groups which enforced segregation practices well into the Jim Crow era of the 1870s. And by the 1900s, police departments began to spring up as a perceived need for the enforcement of these Jim Crow laws.

This dark era of Jim Crow technically ended in 1965 following a bloody civil rights movement when law enforcement officers brutalized, maimed, and murdered Black protestors and leaders all over the country in an attempt to silence their voices. Yet, even at the precipice of civil and social change, enforced by the federal government and codified into law, the policing institution would not go down easily.

In Michelle Alexander’s seminal book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, she documents the subsequent reformation of policing in America from the era of public lynchings to the modern era of mass incarceration and privatized prisons. Presenting the “War on Drugs” as the catalyst for this new era of Black and poor oppression, America’s policing institutions were once more at the center stage. Strategically, and often invisibly, police disproportionately enforced laws against Black men in order to fill for-profit prisons in need of slave labor, subsequently brandishing them as felons in order to maintain the racial caste systems that America was founded on.

This is as brief a history that can be offered; a snapshot into centuries of complex and painful subject matter. But addressing the misinterpretation of the phrase ACAB makes this history both of dire importance and all the more difficult to address outside of the meticulous deconstruction and relearning done in classrooms and universities that, put quite simply, cannot happen in the real world of offices and kitchen jobs.

+

But what of the here and now? What of the so-called good cop that enters into the policing institution with his virtue intact, set on changing the system from within?

In a powerful essay titled “Behind the Blue Wall of Silence,” Thomas Nolan, an ex-Boston Police Bureau Lieutenant of 27 years, deconstructs the deeply ingrained subculture and “cult of masculinity” that policing bureaus enforce and work within. A subculture that he says is “steeped in a deep and historically ritualized set of behaviors and representations intended to set their members and the mechanizations of their inner working as apart from those of the rest of society.” These sets of behaviors, he goes on to explain, are hyper-masculine, hyper-sexualized, homophobic, misogynistic, faux-heroic and warrior-like, and steeped in secrecy under the faux-loyalty of the “brotherhood.”

He offers examples of brutality and ostracization against fellow officers who were perceived as untrustworthy—a trust set in the immoral behaviors of taking bribes and vows of silence. Women and gay men are especially susceptible to this inner-violence upheld by the patriarchal hierarchy, from street cops near the bottom to high ranking officers at the top.

Within this rigid and unchanging paradigm, the good cop as a bastion of higher values and morals, seeking to reform the system from within, simply cannot exist. Those speaking out are, at best, pushed out of the group and placed in roles like clerical work—something Nolan says is deemed as more feminine and thus degraded by fellow officers—and, at worst, brutalized to the point of severe organ damage and near blindness, as in the disturbing case of Michael Cox.

This hierarchy of hyper-masculine, militant policing cannot be changed from within and those who enter it are doomed to fall victim to its inner trappings. You cannot change the system; the system is built to withstand. The system changes you.

+

What makes this such a difficult topic to broach with others who have surely heard the phrase ACAB a million times on every media channel and long-ago made up their minds as to its meaning, is the fact that this subculture of policing and the so-called blue wall of silence has long ago leaked into much of the public’s perception of America’s policing institutions; a perception constructed by police themselves and their faux image of heroics and selflessness.

It’s not just cops waving thin blue line flags now, but construction workers, mechanics, landscapers, painters, welders, and other first responders. All manner of white laborers who think that the attack on the policing institution is an attack on white people themselves and thus white America. In many ways, it is, when you consider the history of whiteness. A people who live paycheck to paycheck perceiving that their way of life is being threatened by holding cops accountable for their actions and misdeeds—by demanding reform and abolition.

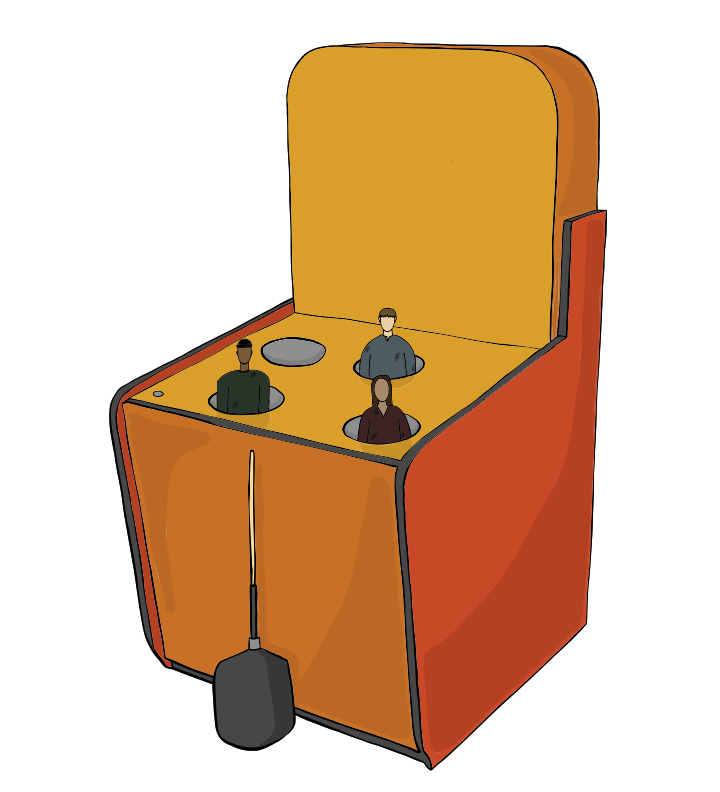

The blue wall of silence where behind cowers a historically violent and discriminatory institution extends well beyond the precinct’s walls and into public domain. It stretches far and wide, upheld by right wing media, funded by corporations for private gain, and fed by the neverending conveyor belt that runs from poverty-stricken neighborhoods to federal prisons. It stretches all the way to your grandma’s living room where her father or uncle or grandad was a cop, and, she insists, he wasn’t a bad man.

ACAB. So short a phrase that can’t possibly encompass what abolitionists mean when they employ it; the history of racially and sexually fueled violence and the deeply ingrained and problematic culture of police bureaus all throughout the world. But if we’re to have radical reform in this country, the blue wall of silence must be torn down brick by metaphorical brick.

Not all cops are bad people. But all cops perpetuate and uphold a bad system.