When first asked about writing a piece for the Sentinel’s latest issue, themed Time, what came to mind were the photographs of Portland State–its buildings, culture, and students–from decades past. My idea was to select several old photographs from the archives and write about them, exploratory essay style. I was ambitious, yet only had a week before the deadline.In the midst of settling into a month-long stay abroad, I convinced myself that I could deliver something polished. To begin, I went through the folders at Portland State’s University Archives Digital Library, selecting several photographs and pondering how time and photography relate to each other. As a result of my research, the draft was a long-winded, rambling, and obnoxiously meta (probably terribly difficult to understand) monologue about, well, Time. Afterward, I took a break from that introductory piece to explore one photograph. Several hours later, I found myself lost, deep within a Wikipedia wormhole that had very little to do with anything. I put the project away. In the meantime, I was busy with family gatherings, et cetera. The deadline came and went. The executive editor followed up with a polite email, and I held my head between my knees. When I finally opened the project back up, it dawned on me that (and let me preface this by stating that the irony is not at all lost on me) I just didn’t have enough time. But not all was lost. It couldn’t be. The photographs were still there, waiting to be seen. The Sentinel was still going to print, and I still had (albeit very little) time. What follows is a series of photographs from the aforementioned archives, each with a brief description.

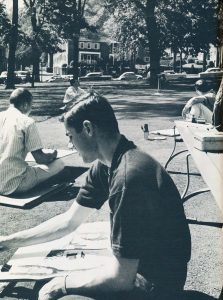

Serenity is art students drawing in the park blocks on a warm day. Those days define, in stark contrast, the days we find ourselves in today, where mats of dark, relentless clouds turn gray everything with color around campus. The facing page fittingly quotes “Humanities bring the ideals of meaning and value into man’s everyday existence. Through forms of expression such as art, music, literature, man himself creates and studies his world.”

The new school year has hardly begun. It’s early October, the 12th, and lectures are wrapping up on campus. Students are released and scurry through the park blocks to their prospective cars, buses, and rides home. Some students stay on campus. All the while, a severe windstorm is sweeping up the west coast. Students must be jarred by a sudden and heart-wrenching pounding, swirling, and shaking. Once it is over, the campus is dark. Those left wander to the cafeteria, a natural gathering place. There, they’re offered free coffee and snacks while they ponder what could have just taken place. That isn’t revealed until the following morning. “Centuries-old trees, providing welcome greenery in the middle of metropolitan Portland were ripped apart in minutes by the unbelievable force of the hundred-mile-an-hour winds. Their tragic mutilation left bizarre forms and impassable obstructions in the previously sedate and orderly Park Blocks.” The scars live on for some time, even after students help city officials clean up the destruction. In the meantime, students continue to walk up and down the blocks, now a little less shaded, on their way to their lecture halls. (This photo came from the city of Portland archives).

It’s the late forties, and in an effort to provide higher education for WWII veterans returning home to Portland, the Vanport Extension Center was founded. A flood two years later wiped it out, along with Oregon’s second-largest city at the time. Written in the yearbook was this: “May 30, 1948, was indeed a sad day. On that day, one of the worst disasters in the history of the Northwest, the Vanport flood, submerging our old ‘U by the Slough’ under fifteen feet of water. It looked like the end for the school that had just celebrated its second birthday.” But before that, several hundred college students gathered at a muddy field to have fun–something so vastly different from war.

It’s the eighties now and the adorned outfits can hardly be distinguished from those of today (save, maybe, the shoulder pads). If it weren’t for several missing buildings from the background, it very well could have been shot recently. 200 Market, nicknamed Black Box, sits menacingly behind two students who I can only imagine are asked to pose and are discussing what to do. That’ll do! I imagine the photographer says.

It’s Party in the Park, 1993, and bewildered, shy (or maybe not so shy) freshmen are waddling around the park blocks while groups and clubs make their case. One table is a magnet, that of the Popular Music Board. As they say, there’s one for everyone. It would have been difficult not to include this photo. Least of all because of the caption, reading “left to right: Kurt ‘Doctor’ Nelson, Brent ‘Bert’ Robinson, Steve ‘Spartacus’ Loaiza, Josh ‘Funch’ Orchard, Jon ‘Juan’ Beil.”

We’ve just sped through four decades, ones in which the Soviet Union rose and fell, 2.2 million men were drafted to aid in the Vietnam war efforts, civil rights leaders were assassinated, power changed hands, and economies collapsed. Amid those global woes, football games occurred, storms persisted, clubs recruited, and students kept showing up. Photography, and its place in time, exposes life’s paradoxes–showing us how students can play football one day and undergo a disastrous war the next. Photos capture these little lives hidden among this greater global one. I hope pondering these photographs has inspired you as it has me. If you’re interested in seeing more photographs, you can visit archives.pdx.edu.

Photos courtesy of Portland State Archives.