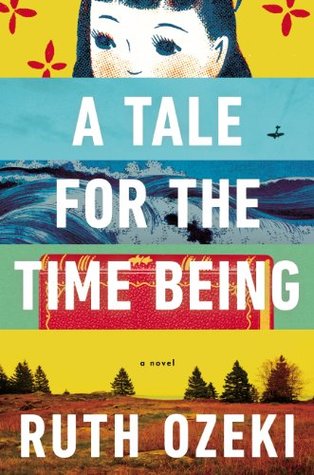

During the first week of the winter term, I went to PSU’s library to return some books. While I was waiting in line, I saw a sign that read: “Free Book: A Tale for The Time Being, written by Ruth Ozeki,” since it was published by Penguin Books I said to myself, “Okay, why not?” Then, one month later, I saw a literary event announcement that said Ruth Ozeki was coming to Portland to discuss her book. Everybody Reads is a community reading project by the Multnomah County Library, which has distributed 8,000 copies of Ozeki’s novel for free, and I was holding one of them! So, I bought my ticket and started reading her book.

Soon after, I recognized that I was holding a Japanese American teenage girl’s diary in my hands, and she was speaking to me! The novel starts with Nao declaring, “Hi! My name is Nao, and I am a time being.” Her incredible voice and humor were engaging and kept me reading more. Later, Nao asked, “Who are you, and what are you doing? Are you in a New York subway car hanging from a strap or soaking in your hot tub in Sunnyvale?” Unfortunately, I learned she was also suicidal, and not only her but also her father. Her Japanese high school friends bullied her because she had returned from America. They even prepared an excellent funeral for her while she was alive and let her watch the ceremony.

Nao and her father, Haruki #2, were my favorite characters. During the time that Nao kept a diary, her father made daily unsuccessful attempts to commit suicide. Another prominent character is Nao’s great-grandma, a Buddhist nun named Jiko. For sure, they form an interesting family. In Nao’s world, Jiko symbolizes life. She had become a nun and went to live in an isolated temple near the mountains. However, the nunnery has internet, and the great-grandmother uses it to communicate with Nao often. The teenage girl admires her grandmother and learns serenity and inner strength from her. For example, Jiko asks, “Have you ever tried to bully a wave? Kick it? Pinch it? Hit it? Beat it to death with a stick?” The waves serve as a metaphor for the passage of time. The wise nun explains fighting with them is futile, their ups and downs are ultimately indistinguishable.

In contrast, Nao’s father symbolizes death, not only because of his frequent suicide attempts, but also due to the overwhelming sense of disappointment that permeates his life. Before, Haruki #2 was a computer programmer in Sunnyvale, California. But they moved back to Tokyo after Haruki’s company went bankrupt. Unemployed and feeling hopeless, Haruki does not know how to cope. Still, his relationship with Nao touches the reader’s heart. They try to learn how to live together and trust each other. But, “How much can you really trust the promise of a suicidal father?”

Yet, Nao is not the only writer in the novel. The book is composed of two interwoven parts, with the chapters alternating between the two. The first is about Nao’s life and her diary. In the second part, we meet a new character, Ruth, living in Canada, who also shares the author’s name. It doesn’t take the reader long to figure out that the author included herself and her husband, Oliver, in the novel. One morning, Ruth finds Nao’s diary lying on a beach on the other side of the Pacific Ocean. She sets out to unravel the mystery of Nao. Where is the teenage girl from, how old is she now, and how did the diary end up on a beach half a world away? The novel’s pace is slower here compared to the first part describing Noa’s life. I looked forward to meeting with Nao again because her voice was more potent than the fictional character Ruth’s. This dilemma made me more eager to listen to what Ruth Ozeki had to say at her event on Thursday night, March 16.

The Keller Auditorium was crowded with all sorts of people, including librarians and even quite a few high school kids. After describing how she loves libraries, Ruth Ozeki started by lecturing about how she writes her novels. She remarked that writing a book takes her ten years and added that random factors influence her stories by saying, “My first two novels were all about food. My Year of Meats was about meat, and All Over Creation was about potatoes.” Her other two novels also share the same DNA. She said, “The Book Form of Emptiness and A Tale for the time being are like siblings. They were both about young people with mental health problems. They both included nuns, and both questioned their environment. Finally, the pair were searching for what was real and unreal. These two books are in conversations with each other.”

The books Ozeki read, the news she saw, the links her husband sent her daily, rumors, dreams, or disasters were all inspirations for starting a new novel. Before starting to write, she described, a book begins to speak with her. “Novels come with a voice,” she claimed. Nao also began to talk to her, and it seemed promising to Ozeki. She highlighted, “If something speaks to you immediately, write it down; otherwise, they will speak with others. From the beginning, I knew that Nao was in trouble. She was writing in English. Nao had a reader in mind. The problem was she didn’t know who she was writing to.” It took five years to figure out that it was for Ruth. After the earthquake and tsunami in 2011 in Japan, she decided to cut off “the reader” part and instead put herself in the novel. She was going to be the reader of Nao’s diary.

I don’t think Nao needed a reader who was part of the novel. While reading her diary, I felt she was writing for me, not for the fictional Ruth. Therefore, I would have been happy reading just her story. In addition, adding the earthquake and tsunami, in my opinion, was not needed. It didn’t fit with Nao’s life or her feelings. While reading these sections, I asked myself, “Why am I reading this now?” She wanted to include the disaster in her novel. Later, she explained why in her two books, A Tale for the Time Being, and The Book Form of Emptiness are like siblings. Ozeki revealed that she created the later book with the pieces she had cut from the former. She has a “dumb” folder on her computer where she puts the things she writes but hasn’t used yet, never the one to waste.

Ozeki also stated that she always puts herself into her books. “Every character is a facade of the writer. So how did I write like a suicidal teenager? Because I was a suicidal teenager when I was young. Putting some versions of myself requires trusting in me.” For me, this part was the most memorable part of her speech. She talked about the years it took for her to learn how to trust her writing and readers. She said, “Learning to write is learning to trust.” You need to trust yourself, your characters, and your readers.