And why take ye thought for raiment? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow: they toil not, neither do they spin.

—Matthew 6:28

When the Buddha was at Mount Grdhratuka, he held out a flower to his listeners. Everyone was silent. Only Mahakashyapa broke into a broad smile.

—Mumonkan (The Gateless Gate or The Gateless Barrier), Case 6 (excerpt)

People generally conceive of religion as sets of competing—and mutually exclusive—metaphysical and ontological claims. Propositions such as the existence of an omnipotent and omniscient being, a substance or essence separate from the physical body that survives death, and one or more realms to which this nonphysical essence travels after death cannot be proved or disproved. Despite their continued popularity, other doctrines—such as the earth being six thousand years old, the geocentric arrangement of the solar system, and coexistence of human beings and dinosaurs—are demonstrably false, and have been so for generations.

Religious institutions have traditionally urged (with great force and violence for most of human history) adherents to accept these doctrines on faith. When I spoke with Swami Chetanananda of The Movement Center in NE Portland, he emphasized this history of religion as a form of social control. According to Swami, the major religions of Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism were codified by empires to support their own power structures. Much as the Romans adopted and promulgated Christianity as a state religion, so too were the other great religions systematized and propagated by their respective imperial advocates. Under the guise of speaking with divine approval, religious institutions of all kinds continue to direct and control life around the world.

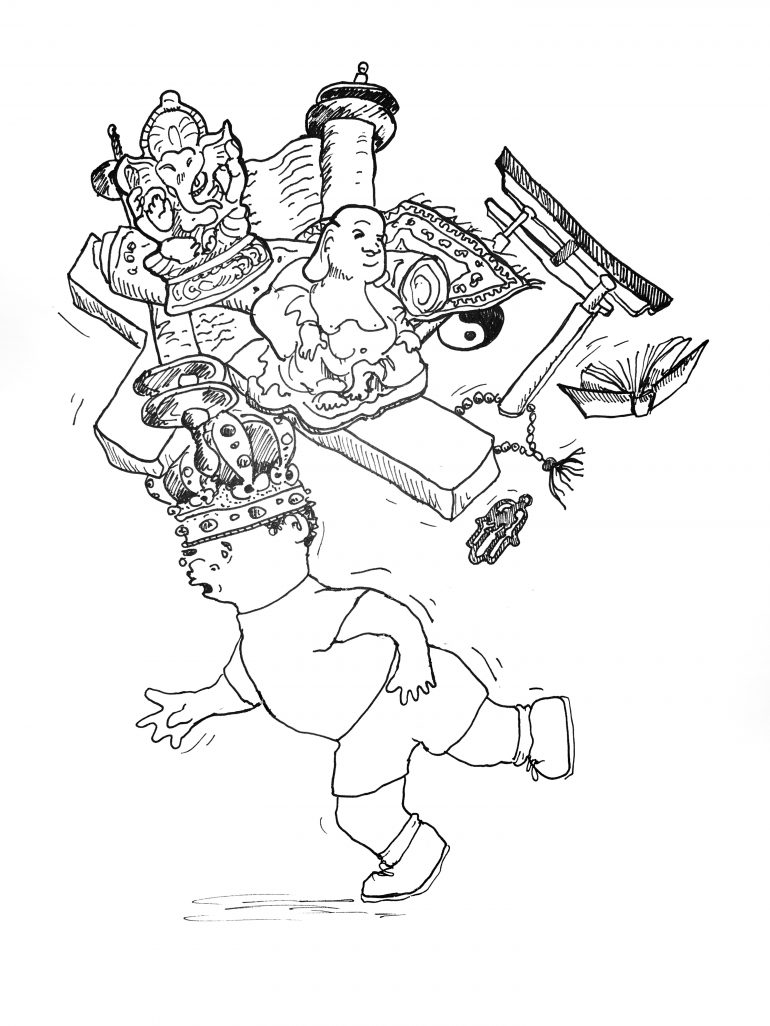

Given the problematic political origins and history of the major religions, a bit of skepticism regarding their usefulness seems in order. Rinzan Pechovnik, Osho of Portland’s No-Rank Zendo (a group of which I am a member), says that every major religion “can become so lost in its myths and rituals that it becomes fanatical.” However, there is “an expression of deep truth” in each one. The purpose of religion, after all, is to use “rituals and rites, myths and icons to point the mind to a higher power.”

Instead of continuing to pit one set of metaphysical assertions against another, let us instead ask the question that is hardly ever asked: How can we look past doctrine to experience “deep truth”?

Not only can we never finally and decisively prove that there is or is not a soul separate from the body (or any other similar claim), but it is not at all clear that it matters. Would definitive proof of a soul end war and bring peace in our time? Or, regardless of the objective truth of the matter, would forcing every living person to agree to believe in the same conjectures alleviate human suffering?

According to the Majjhima Nikaya, a text in the Pali canon of Theravada Buddhism, the Buddha refused to respond to questions about the eternality of the universe, the existence or nonexistence of a soul, and a number of other queries; these are known as the unanswered questions. That these questions were just as familiar and vexing two and a half millennia ago as they are now ought to give pause for thought. Perhaps we are fooling ourselves into thinking syntactically correct propositions and questions are not only sensible and possible to answer, but that the answers matter.

The answers do not matter. This was the Buddha’s position, and the view of many mystics, skeptics, freethinkers, agnostics, and doubters before and since his time. We have become caught in elaborate word games that purport to refer to the nature of reality, but in fact refer to nothing other than themselves.

Although the questions (and proposed answers) are irrelevant, the urge to ask is clearly an intrinsic part of being a sentient being, a human.

Who am I?

What is this life?

Why?

Treat these conundrums not as problems in need of solutions, but as questions in need of continual asking, of ongoing meditation. This brings us beyond metaphysical propositions, to the original impulses at the heart of all the religions. Before the terrorist attacks, crusades, witch-hunts, and all the other unsavory aspects of institutional religion there existed one impulse: to point toward the absolute.

Each tradition names the absolute differently: God, the Void, Buddha-nature, the Absolute, the Beloved, Ultimate Reality, Christ, I Am that I Am. These terms act merely as a finger (or fingers, for the ecumenically minded) pointing at the moon; the finger does not hold, or even touch, the moon—it simply directs attention. Much of religious practice since the advent of writing has focused on the finger—God’s name, how many aspects he or she has, the nature of afterlife realms, characteristics of proper attire for the clergy, and so on—when really the finger is only a tool to turn toward the moon.

This old analogy uses the moon as a symbol for the reality of life, without reference to anything else. When I interviewed Kakumyo Lowe-Charde, co-abbot of Dharma Rain Zen Center in NE Portland, he spoke of the “sacredness of the mundane.” He summarized the importance of appreciating every aspect of life in a few words: “This really matters.” Relying only on immediate and direct experience unmediated by doctrine will provoke uncertainty. Lowe-Charde stressed the importance of tolerating ambiguity. Only when we allow ourselves to tolerate paradox and ambiguity in our investigation of the mystery of existence do we truly appreciate the wonder and beauty in all of creation.

Let us, then, turn away from the finger and all its tyranny of thoughts and doctrines; to the moon, and the state of non-knowing, let us look.