The subheading on HBO Max describes Mark Mylod’s The Menu as a “delectable horror satire.” Perhaps that’s partially right. Satirical horror, as a genre, is generally considered comedic. The Scary Movie franchise, for instance, or from a certain perspective, Violent Night, the new David Harbour flick in which he plays the most unhinged Saint Nick ever put to screen. In The Menu, however, there is less comedy present and more of an introspective hypothesis. What if there was a chef, on top of the world, who lost his mind due to the pressures of his position?

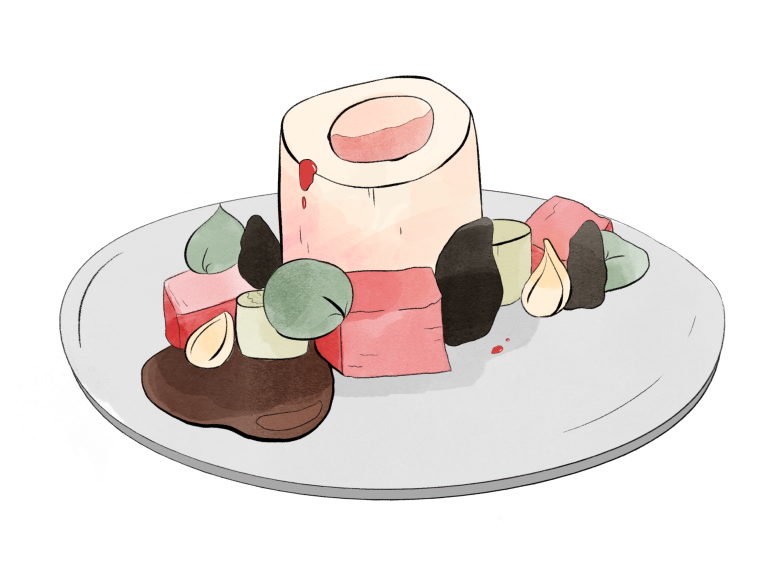

The Menu is part power fantasy, part horror movie, part social commentary. “Margot,” played by Ana Taylor-Joy, is a guest of her presumed partner Tyler on an island home to one of the world’s best restaurants, Hawthorn, run by Ralph Fiennes’ Julian Slowik, an internationally famous chef. Their specialty is bread. Halfway through the meal, which is presented by the movie and the chefs in several courses, conveniently diagrammed in tastefully-shot mini-presentations which interrupt the characters and the plot, much like on a cooking show, one of the chefs kills himself because, Slowik explains: “He will never be great.” This begins a long chain of similarly shocking scenes which takes the plot roaring to the end of the movie.

Burnout, which is referenced literally at the climax of the film, affects everyone, no matter how passionate they are. It is a creeping sensation of disillusionment that eventually takes over your mind and won’t let you enjoy the things you used to love. Passion, burnout’s opposite, is a force which can drive people to reach heights they never thought they would, but without time to rest and enjoy the fruits of their labor, every person will eventually succumb to dreaded burnout.

It is an unfortunate reality of the creative world that although you may love to do something, the minute you are forced to do it for a living, or out of some expectation that you ought to, or even due to internal pressures (you feel you should, or you’d let people down, or you have to prove it to yourself you can), you begin to lose your love for it. This is what drives so many creatives to drugs, alcohol, or suicide. The cycle of burnout is vicious. To be a great artist, and particularly a great chef, is to be tortured, the film argues, and this torture is due to the commodification of culture.

The critics, the fans, the rich douchebags who only eat at your restaurant for status, even the loyal regulars; all of these people are contributors to this commodification. Julian Slowik has been ripped apart by his own success, and cannot live with himself anymore. Therefore, he decides to (spoiler alert) symbolically commit self-immolation, and take all of the people who have caused his grief over the years with him. (It is with noting that the film makes clear it was not Slowik’s original idea to kill everyone, but one of his chefs, Katherine).

This critique, presented obliquely by The Menu, is indicative not just of the problems with the food industry, but with art as a whole. Slaving away to your passions is not sustainable.

During the COVID-19 pandemic (which was due in no small part to climate change) many food worker’s jobs were put at risk. Some turned to Doordash or other delivery apps, some tried to sustain themselves with unemployment and stimulus checks, and others simply gave up. The service industry is cutthroat without any complicating factors, and a global pandemic which forced many restaurants to either close entirely or significantly cut back on staff led to a work environment that was even more stressful than before.

Part of the appeal of making food is seeing how people will react when they eat it, but when even that is taken away, the job becomes soul-destroying. Most restaurants that survived switched to to-go orders only. Workers became machines on a production line, the intermediaries between the red-bag-holding college kids standing in their lobbies on their phones and the faceless clientele, and burnout set in in droves. One can’t help but believe this paradigm shift had something to do with the writing of The Menu.

The crux of the film, the most intense scene not because of stakes or high drama, but because of its implications, is when “Margot,” who was not on the original guest list and has in fact been hired as an escort by the Slowik megafan (and detestable person) Tyler, orders a cheeseburger to go. A slightly ridiculous premise to build the core of the film on, but the acting carries it through. The message here is not necessarily one of value judgment: a cheeseburger is a simple dish, made millions of times a day across America, and Julian Slowik, we learn in the film, used to be a line cook. He has secretly kept his old “Employee of the Month” plaque, even here at his insanely overblown and pretentious food Eden.

It is a symbol of the early beginnings of an artist, a reminder of where they came from, the passion they used to have, the ambition and the regret of fulfilling their dreams only to lose their love for the craft which drove them to create in the first place. And so the cheeseburger is a reminder of the passion he once had and has since lost; he lets her go.

Occasionally ham-fisted as it may be, The Menu is still an interesting angle on the contemporary artist’s dilemma: make money or enjoy life? Or, to put it another way: you can’t have your cake and eat it too.