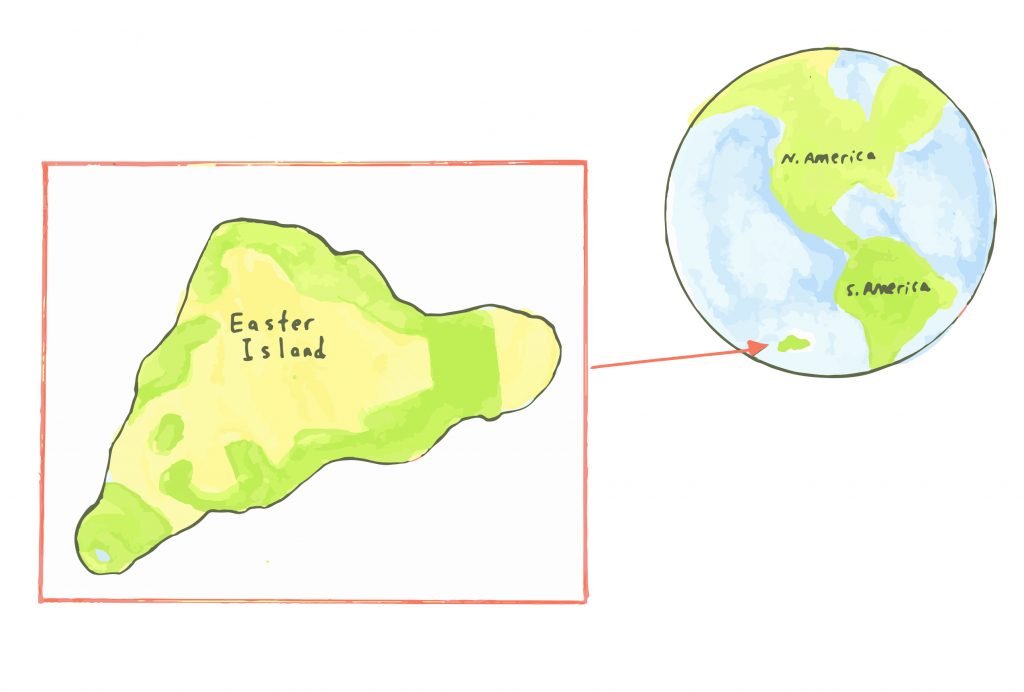

It is astonishing to witness how art touches people. Art presents itself to us in numerous forms. To the untrained or rather busy eye, a painting or a sculpture is just another piece. But to the select many, art has a connection, a relationship that is unique to every individual. This bond may at times be a bond with the self, or it may be a contract with many souls. It speaks a language of its own when the pledge runs deep and becomes enrooted in and as a culture. When an object with such abstract emotion is kidnapped and forcibly removed from its native land, a sacred link is tarnished. Such is the case with the Moai statue that now sits under a spotlight in the British Museum. The word Moai is used to refer to the head-like figures carved by the inhabitants of Easter Island in Eastern Polynesia, known as the Rapa Nui.

Museums across the globe harbor pieces that were once part of a country’s culture and history. To address them as pilfered art makes sense; however, calling them stolen, looted, or uprooted is not actually possible because of the complexity of their origin stories. Statues and other art we see in museums, especially those acquired from foreign lands, have stories they stand on. These artifacts have voices that remain silent, and their stories untold. However, the scenario is different for the Moai statue that sits in the British Museum. According to an article by The Independent, the Moai statues of Easter Island were left to rest on the island about 150 years ago. Their peace was soon disturbed by the HMS Topaze captained by Richard Powell. Taken during an expedition by the British Royal Navy, the Moai is one of many artifacts looted during the reign of the British Empire. Upon its arrival on English soil, the sailors presented the Moai to Queen Victoria in 1869. Her Majesty then decided to donate it to the British Museum, and the Moai has been a part of the collection ever since.

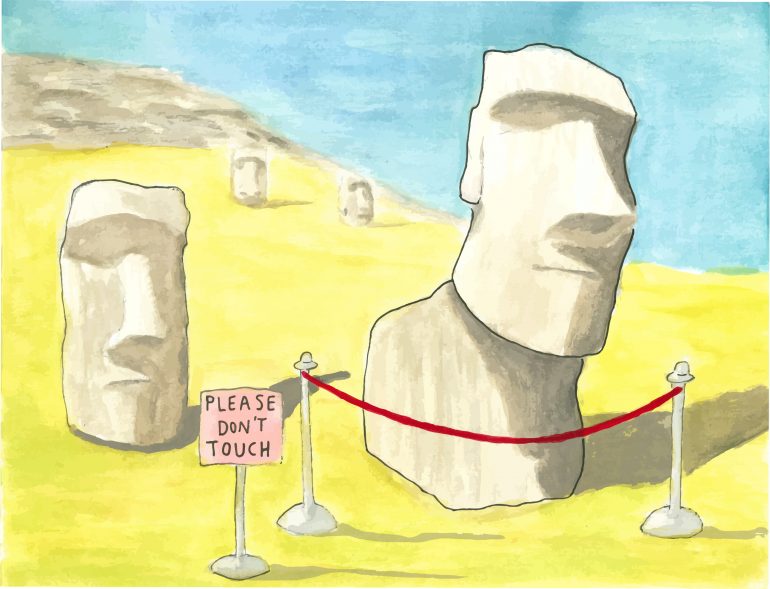

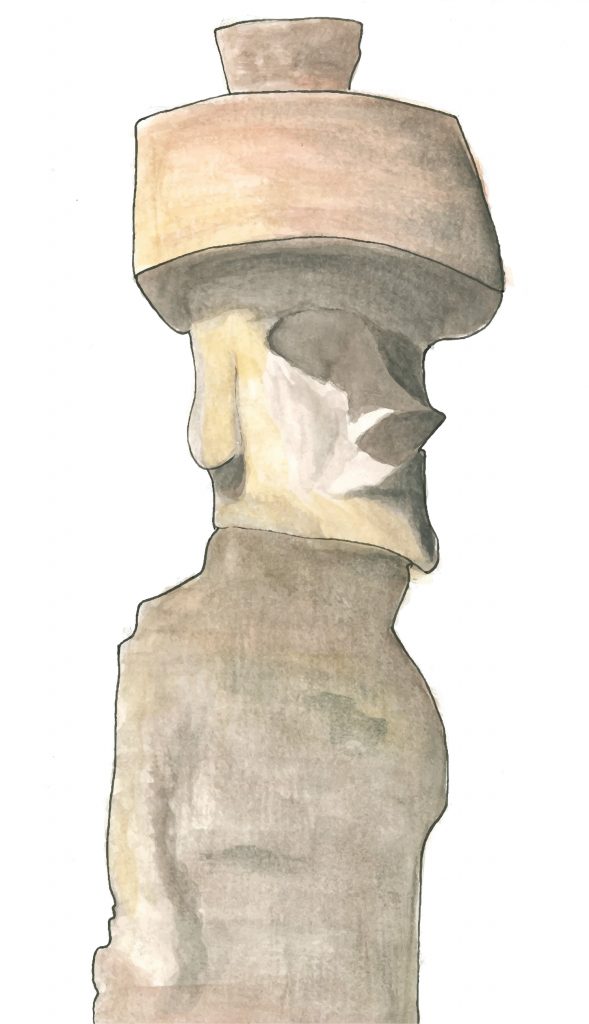

There was a very good chance that this Moai would just be in thousands of photo albums in phones and cameras, had it not been for the voice of the Rapa Nui people. With support from the Chilean government, the Rapa Nui people have given the Moai in the museum life. The statue has successfully made headlines, not just because it is news, but because it opens up debates on museums and their possession of foreign artifacts. Last November, The Rapa Nui met in London with representatives from the British Museum to discuss returning the statue. There is this extremely personal connection we see here, where the people are asking for a piece of their soul back. The natives have named the statue Hoa Hakananai’a, which translates to “the lost or stolen friend.” Hoa Hakananai’a stands tall at the entrance of the british museum’s welcome gallery. The 2.5 metre statue of basalt greets numerous visitors from around the world, whereas, it should be on Easter Island, carrying the spirit of the island’s ancestors. The spiritual qualities of the statue were highlighted when Anakena Manutomatoma, who serves on the island’s development commission told The Guardian, “We want the museum to understand that the moai are our family, not just rocks. For us [the statue] is a brother; but for them it is a souvenir or an attraction.”

I believe the situation of the Moai, Hoa Hakananai’a, and the how the British Museum handles it, will set an example to use for similar scenarios. I believe this should lead to an interesting debate, both weights on the scale are very important and do not necessarily outweigh each other. One cannot surely deny that the statue at the British Museum is kept with the best of care and preservation and so are other rare pieces. To return these statues and put them up for display in its once natural state may cause more harm than good. The change in climate alone will be a major problem to tackle. Will the native and in fact rightful custodians of the statue be able to provide the same exact environment the statue has been in for the last 150 years? Furthermore, it must also be considered that the Moai at the museum offers many people the opportunity to educate themselves about the cultures and history of Easter Island without having to go the islands themselves; although this is a very tourist orientated opinion, it does hold some truth. To ease the tension of the claim of ownership, the Museum can declare that the statue belongs to the Rapa Nui people, and acknowledge the complicated history of how the statue came to the Museum. However, to return the statue to the island, in my opinion, may result in more damages than benefits.

Personally I would not like it if someone took something of value from my home and kept it away until it became nothing more than a memory to me. But the Moai isn’t a decoration piece, nor is it a subject of light ridicule. It is personal to the Rapa Nui people, and, by all means, a part of their heart. However, the past has shown us that a power imbalance between imperial nations like Britain or the United States and indigenous people creates a very unfriendly equation of power and rights over indigenous art. Regardless of it being snatched away, it has become a part of the word “history” and has been given a global platform. All the Moai needed was a voice, and thanks to the Rapa Nui people, it now speaks to us in words we know.

There is no right or wrong way to understand the complication of this Moai’s rightful place, but perhaps the poem, “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles,” by John Keats, will help the reader by providing a lens or two of perspective. The Elgin, also called the Parthenon Marbles, is an artifact laced with a history of debate and politics. Like the Moai, it is displayed in the British Museum, on a global platform, voiced with that of John Keats. His poem speaks of the marvels of human creativity and how it can outlast its creators. With regards to perspective, the poem is cloaked in sadness and I believe that is one perception that can hardly be wrong. For the Moai, the debates and politics may outlive us all, but the thought that it may never return to its rightful place, scars the hearts of those who share theirs with the Moai.