Hours before sunrise on the morning of June 28th, 1969, members of the LGBTQ community fought back against a police raid at a New York City gay bar known as The Stonewall Inn. This incident, known today as “The Stonewall Uprising” or “The Stonewall Riots,” was a historical moment in which queer people began to demand that their right to exist be acknowledged; this event is widely credited as the major turning point for the LGBTQ Rights movement in the United States.

June 28th of this year will mark the 50th anniversary of The Stonewall Uprising. In the half-century since Stonewall, this country has seen progress in the establishing of anti-discrimination laws, marriage equality, and a greater sense of understanding from the U.S. population in general. We’ve even see examples of this progress in the recent history of the State of Oregon: Oregon’s 2015 decision to ban conversion therapy (making it the third state to do so) is a huge leap forward from Oregon’s 1992 Proposition 9, which would have amended the Oregon Constitution to define homosexuality as “abnormal, wrong, unnatural and perverse.” Yes, we’ve come a long way.

While it’s important to acknowledge these steps forward since Stonewall, it’s equally important to remember that we in the United States, despite having many steps left to take, are lucky to have had a historical moment like Stonewall. Many LGBTQ activists around the world are still fighting for equality in countries where such progress has yet to be made; they are still hoping for their Stonewall turning point. It is the intention of this article, to be serialized over the next several months, to highlight some of these activists, to examine the discrimination against which they are fighting, and to consider the implications of their continued struggles for our post-Stonewall society here in the U.S.

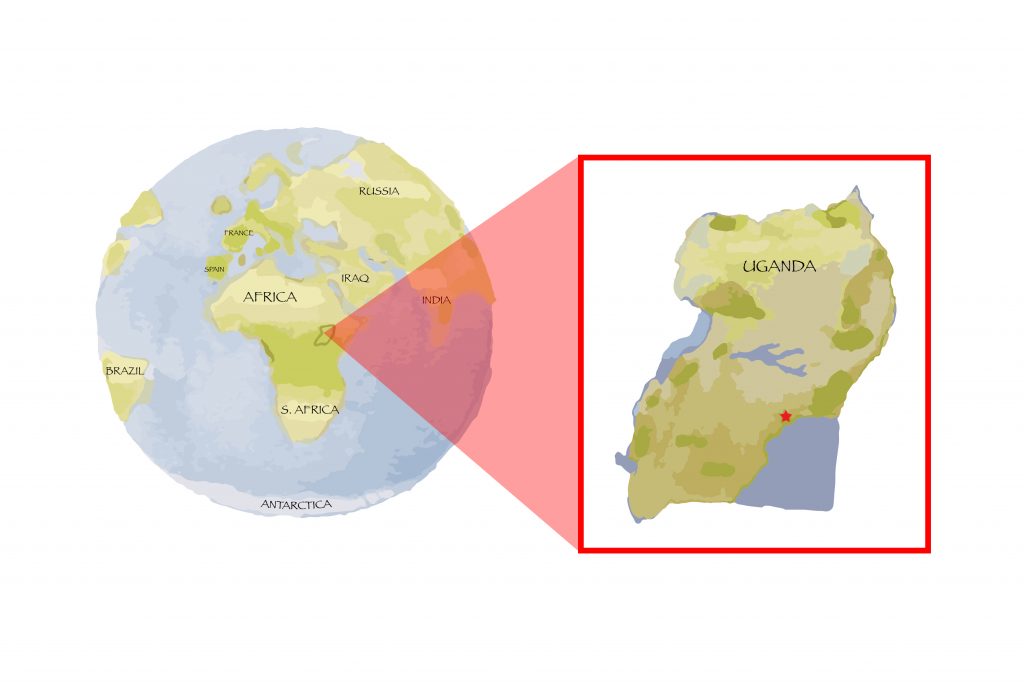

Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera and the fight for equality in Uganda

The peoples who now make up modern day Uganda mostly accepted homosexuality and bisexuality prior to Western cultural influence. Due in part to Western colonization in the 19th century and the work of religious missionaries then and now, Uganda is one of many African nations that experienced a significant regress in its views on queer individuals since the area was first colonized. In the first years of the new millenium, this regress worsened in Uganda. Politicians and people in power have propagated and legalized homophobia in such ways that many analyses have suggested that homophobia is currently being used as a political tool in Uganda. The nation has seen both the introduction of new anti-queer laws, and the strengthening of existing discriminatory laws, which have caused a growing attitude of hostility against queer people. A 2013 survey conducted by Pew Research Center found that Ugandan citizens over the age of 50 had the highest rate of acceptence toward LGBTQ individuals, indicating that the increase of discriminatory legislation is affecting the younger generations’ views toward queer people. Sections 145 and 146 of Uganda’s Penal Code Act states that any individual who acts “against the order of nature (i.e. is homosexual)” can face up to seven years in prison. Furthermore, Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Act, which would call for a lifetime prison sentence for people convicted of being queer, could still become law. But alongside this increase in discrimination has come an increase in Uganda’s fight for LGBTQ rights, exemplified in the life of activist Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera.

A turning point in Nabagesera’s life was the day her mother, speaking to the president of the University Nabagesera was attending, asked that her daughter be allowed to finish her degree, despite suffering from an incurable sickness—by which her mother meant Nabagesera’s lesbian identity. Despite what must have been a difficult moment, Nabagesera is grateful to her mother for this action. She has since clarified that her mother, who was accepting of the fact that her daughter was a lesbian, was only doing what she felt she must do in order to prevent the University from expelling Nabagesera on the grounds of her sexual identity. This moment acted as a catalyst for Nabagesera to educate herself and her community about LGBTQ people, and the underlying reasons for Uganda’s cultural hostility against them.

Nabagesera recalls witnessing a great deal of discrimination during her upbringing in Uganda, from the call for the genocide of homosexuals preached from church pulpits, to an actual expulsion from school at the age of 13 for writing a love letter to another girl. It was not until she was at university that she first made the connection between her lesbian identity and the struggles she faced in her society. This initial realization led her to pursue human rights activism after she graduated, despite having earned her degree in accounting. It also inspired Nabagesera in 2003 to form “Freedom and Roam Uganda,” a group for queer women, which is the first official queer organization in the country. The successful creation of this group earned Nabagesera the title “Founding Mother of Uganda’s LGBTI Movement.” To this day, the organization continues to campaign for queer and women’s rights in Uganda.

Nabagesera’s new-found activism also garnered a lot of negative attention. In October of 2010, the Ugandan magazine Rolling Stone (no affiliation to the American publication) released a list of names of queer Ugandans, along with their home addresses and photographs of the individuals, published under the headline “Hang Them.” The magazine promised queer individuals would continue to be outed in the coming issues. Three people on the initial list, including Nabagesera, stepped forward to sue the magazine for violating Uganda’s constitutional right to privacy. Nabagesera and the other plaintiffs won their court case in January of the following year, though the celebration of this victory did not last long.

On January 26th 2011, just two weeks after winning the case, queer activist David Kato (who was also outed in the aforementioned magazine article, and who was one of the plaintiffs against the magazine) was bludgeoned to death with a hammer in his home. The preacher conducting Kato’s funeral used the opportunity to demonize homosexuals, further exemplifying the major role that evangelical fundamentalism plays in propagating homophobia in nations across the world. While Ugandan officials ruled Kato’s death to be unaffiliated to his activism, Nabagesera does not believe this to be accurate. In a speech given in 2015, Nabagesera credits this incident as the moment she realized how dangerous and important her activism is. And in fact, Nabagesera’s activism became more focused after Kato’s death.

In 2014, Nabagesera campaigned against Uganda’s proposed “Anti-Homosexuality Act,” which would have made homosexual relationships punishable with life in prison. Though the bill garnered surprising support from the community, due in large part to the rhetoric of influential figures supporting the bill and misinformation from the media, The Anti-Homosexuality Act was eventually defeated on a technicality. However, there are currently supporters inside and outside of the government attempting to reintroduce the bill. Nabagesera then went on to found the magazine Ms. Bombastic, a magazine aimed at at exposing anti-gay rhetoric in the media and telling the stories of LGBTQ individuals in and around Uganda. The ultimate goal of the magazine is not only to create a space for queer individuals to tell their stories and live more openly, but to create a resource for the public at large to become more informed about and familiarized with queer topics.

In 2015, Nabagesera was awarded the prestigious The Right Livelihood Award. She has become a globally recognized voice among LGBTQ activists, and, despite continued discrimination, still lives in Uganda; she has said many times that leaving her home (by which she means Uganda) is not an option. She continues to encourage LGBTQ individuals to live their lives openly, believing that this is a necessary first step in progressing the conversation around queer individuals.

Continuing to Live Openly

Nabagesera encouraging queer individuals to have a willingness to be open about their queer identity continues to be an important aspect of the fight for LGBTQ rights not only in Uganda, but here in the United States. Being open about one’s queer identity reminds society that queer people are real people, and that they deserve to be recognized as such. It might seem like we as a society are past the need to remind others of the existence of LGBTQ individuals, but Vice President Mike Pence’s 2018 AIDS Day speech argues the contrary. In a speech delivered on December 1st (AIDS Day) 2018, Pence failed to mention anything about the LGBTQ community, a community both devastated by the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, and still disproportionately affected by the virus to this day. Furthermore, the Trump administration failed to recognize Pride month in both 2017 and 2018. And the erasure of the LGBTQ community has not always been so passive in the last few years. Let us not forget President Trump’s sudden July 2017 announcement, via Twitter, that transgender individuals would no longer be allowed in the U.S. military “in any capacity”; or that the Trump administration might legally redefine gender in such a way as to imply that transgender people do not exist. How familiar Nabagesera’s words from her The Right Livelihood Award acceptance speech sound to us: “The structures that are supposed to protect me, are the structures that are violating me.”

The need for queer individuals and queer allies to be open about who they are remains an important need. It is a foundational step in preventing such erasure as that implied by Pence’s AIDS day speech or Trump’s anti-transgender attitudes—that subtle rhetoric validating the misconception that queer people do not deserve recognition, or that they do not exist at all. But perhaps the most influential reason for openness is, as Nabagesera implies, simply to demystify queer identities to those who, based off misinformation and the unknown, fear the LGBTQ community. It is easy to fear the perceived “other,” but it is difficult to fear a neighbor you know and respect.

“And then we came out and showed our faces, and there was a change, a shift of attitudes. People were like, ‘Oh, they are real people.’… That already is improvement.”

—Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera