This article is the second installment of a two-part series on The Green New Deal and the Portland Clean Energy Initiative, the first article can be viewed here.

Ambitious Change in Portland

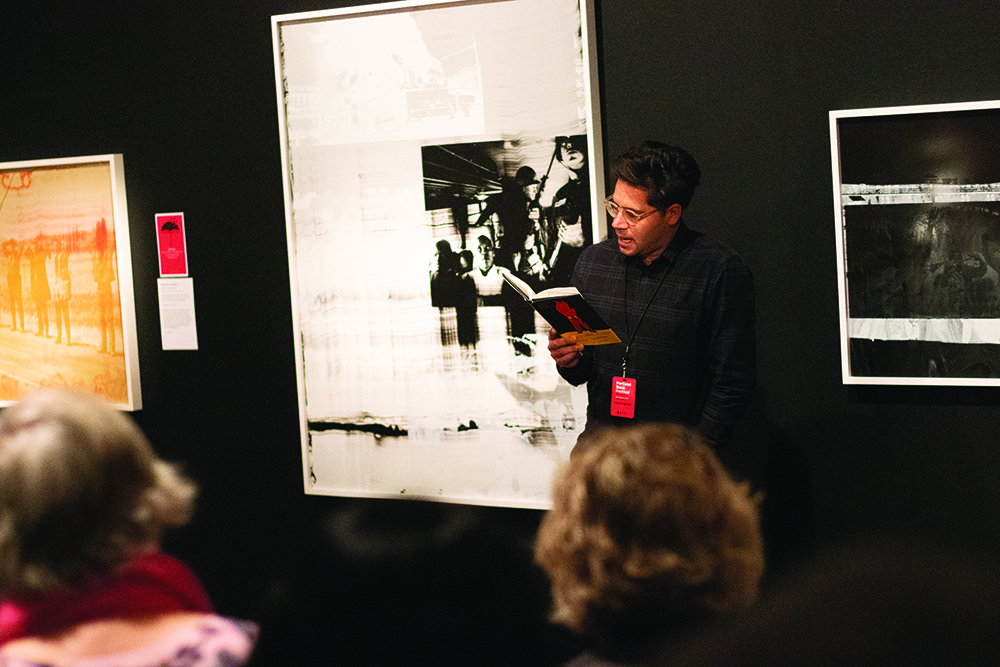

According to Megan Horst, a professor at the PSU Toulan School of Urban Studies and Planning, the Green New Deal is “too narrowly focused on climate change.” Horst cited Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s book, As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance, “We should be thinking of climate change as part of a much longer series of ecological catastrophes caused by colonialism and accumulation-based society.”

It was in this vein that CNN commentator Van Jones referred to the Portland Clean Energy Initiative as “the most important ballot initiative in the country.”

What is the Portland Clean Energy Community Benefits Fund?

The Portland Clean Energy Community Benefits Fund aims to address both environmental injustice and social inequality. The measure, which passed in spades last November, will levy a 1% tax on corporations that make over $1 million nationally as well as $500,000 in Portland (excluding groceries and medicine). The tax will only affect big businesses like Walmart, Kmart, and Target. It is expected to generate somewhere between 30–80 million dollars a year. The revenue will be used to generate a green energy workforce in which frontline, underserved, and low income residents will be given job priority. The revenue will fund projects for the green workforce, such as offering incentives to maximize energy efficiency and home weatherization.

Professor Horst is is deeply engaged with issues like environmental sustainability, community development, social justice and equity. PSU’s Toulan School of Urban Studies and Planning, according to the website, “plays a big role in deconstructing some of the myths of Portland as a sustainability paradise.” The Portland Clean Energy Fund, according to Horst, is a good start. “The Portland Clean Energy Community Benefits Fund is an important step toward a more sustainable, equitable city,” Horst told The Pacific Sentinel. Like the Green New Deal, the Portland Clean Energy Fund aims to promote environmental sustainability and social justice, an aspect that Horst finds appealing but worth monitoring. “All projects are supposed to both reduce greenhouse gas emissions and prioritize Portland’s underserved populations and neighborhoods including communities of color and low-income residents. A challenge is going to be to ensure that green improvements benefit renters (not just owners) and that they do not inadvertently contribute to so-called eco-gentrification.”

To gauge the Portland Clean Energy Fund’s success, Horst says says it will be important to “track data over time” and to “consider the full range of costs and benefits of the program, beyond just the economic ones.” When it comes to assessing the impacts of legislation like the Portland Clean Energy Fund and the Green New Deal, Horst stressed the importance of using qualitative methods in addition to quantitative methods, which, she said, could entail “interviewing or conducting focus groups with organizations receiving funding, employees with new green jobs, and with the supposed beneficiaries.” Analysis, she said, will rely on keeping government interventions “transparent and accountable to their espoused goals.”

While the politics behind an economic overhaul can be overwhelming, the fact that the conversation is happening at all is encouraging. Horst for one is “excited by some new energy in politics around action on environmental and social issues, because it is needed.” But the biggest constraint she says will be keeping corporations in check. The reality, Horst says, is that “powerful interests like Big Oil, Big Coal and Big Agriculture are making a ton of money off of the current system,” and many decision makers “have not stood up for the public interest.” Meanwhile, “many others, like family farmers, are trapped by policy and markets on an endless treadmill of production without the support to implement more sustainable and just growing practices.”

Overall, it’s a battle worth fighting. “I also don’t think we need fine-tuning or modest reforms right now,” Horst said. “We need huge changes if we are going to stave off the worst of climate change, start repairing our relationship with Earth, and address the massive level of social inequalities.”

Creating the Portland Clean Energy Community Benefits Fund

Portland City Council Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty conceived of and organized the coalition that spearheaded the Portland Clean Energy Community Benefits Fund. Soon after taking office, Hardesty spoke at the Audubon Society’s Nature Night about the lessons she learned as a community organizer, like how to assemble a successful coalition around an ambitious vision.

Years before Hardesty began work on the Portland Clean Energy Initiative, she learned a few things as a member of the Environmental Justice Action Group (EJAG). Hardesty said she found EJAG “didn’t really understand what environmental justice looked like” or how to be “inclusive of communities of color as frontline communities who are suffering from many of the environmental issues that we were confronting.” Consequently, Hardesty set out to build a coalition in order to mend the divide between environmental and social justice.

The coalition, Hardesty said, was built to “look like those frontline communities” that are disproportionately affected by climate change and who often don’t get invited to the planning table. That coalition includes organizations such as The Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon, Coalition of Communities of Color, NAACP Portland Branch 1120, Native American Youth & Family Center, OPAL/Environmental Justice Oregon, and Verde.

Initial Criticism

Critics of the Portland Clean Energy Fund argued that the tax would ultimately come back to haunt consumers by jacking up prices. In an article published by The Oregonian’s Editorial Board, the authors argue that “low-income residents will feel it [the tax] the most.” Others, however, (including Hardesty) are skeptical. Hardesty said “it was kind of hysterical listening to the Portland Business Alliance”—one of the largest critics of the Portland Clean Energy Initiative—“talk about how this was going to be devastating for low income community members.” She elaborated, “they came up with some weird number—‘it’s going to cost every low income household x number of dollars a year if this measure would pass,’ right? with no analysis behind it to say why that would be.”

Critics of the Portland Clean Energy Fund also argue that more could be accomplished for environmental and social justice by working from the state level compared to the city. The Oregonian Editorial Board argues that voters should put “faith in a statewide solution,” instead of a city resolution, which they argue isn’t thinking big enough, considering Oregon is looking to “similarly address this need” to combat climate change.

Hardesty argued that environmental activists, including herself, have been trying to pass comprehensive climate reform like the Portland Clean Energy Fund at the state level for years with little success. Just last November, voters from Washington and Colorado overwhelmingly voted down initiatives that would have implemented a carbon tax and set limits on gas and oil drilling after the oil and gas industry spent roughly $73 million funding campaigns to reject the initiatives. This, Hardesty says, is why scaling down to a city resolution was necessary, “we knew that if we waited for Salem to act, that it may not be the legislation that we were looking for and it may not impact the communities that want to be impacted first,” she said.

The Portland Clean Energy Fund vs the Green New Deal

Now that Hardesty is in office, her number one priority is to make sure the Portland Clean Energy Fund is rolled out as intended. She’s wary of corporate interest coming for the fund’s tax revenue, of “people trying to get their grubby hands on this money.”

Professor Horst had similar concerns over the Green New Deal since “it does not offer concrete policy direction.” Horst sees risks in that ambiguity, such as getting co-opted by corporate interests for corporate gains, or prioritizing technological “solutions” and “green growth” over structural reforms and deep social change the country needs to become more sustainable and just.

Conversely, the Portland Clean Energy Fund does offer clear policy direction. The challenge, according to Hardesty, is going to be making sure that the money generated from the fund is headed in the right direction. Hardesty wants to “put a community oversight committee together,” elaborating, “We [the coalition] had some very specific criteria in our measure about who should be on that oversight committee. We certainly need expertise from the energy community, but we also need to make sure that those frontline communities are represented so that we can make sure that those dollars really do go where they’re supposed to go. Our goal is to make sure that we are training the workforce of tomorrow.”

Is the country ready for big climate policy?

The Green New Deal has undeniably sparked a national debate, and a divisive one at that. Despite the near unanimous agreement among climate scientists that climate change needs to be addressed as soon as possible, it just one more point of contention that falls along partisan lines in America. However, in the “Climate Change in the American Mind” survey, when the policies were presented outside of political associations, the results were not as partisan as expected. The bi-annual survey, conducted by Climate Change Communications programs at Yale and George Mason University, showed that 81% of registered voters support the broad goals of the Green New Deal to some degree. In a poll conducted by NBC and The Wall Street Journal, 66% of Americans said they want to see something done about climate change. 13 of the 21 Democratic Presidential Candidates support the Green New Deal, including 6 current Senators who have cosponsored a Green New Deal resolution in the Senate.

The Portland Clean Energy Fund could serve as a model for other cities to follow. “I think two years from now,” Hardesty said, “we will see these measures popping up all over the country, because I know that there are at least 35 cities waiting to see if Portland was going to be able to pull this off.” In that light, it seems more feasible for states—and even the country—to follow suit.

While the Portland Clean Energy Fund passed handily with Multnomah County voters, in the same midterm election, an ambitious state measure in Washington to impose a carbon-tax on greenhouse gas emissions failed to pass. According to Commissioner Hardesty, one key to the Portland Clean Energy Fund’s midterm success was what she called “eyeball-to-eyeball communication,” the aggressive in-person outreach from her coalition. “The groundwork” with voters, Hardesty said, was already laid down by the time anti-tax corporations began their negative ads. By talking about the vision, and “meeting people where they were,” in community meetings and house parties, Hardesty said the coalition was able to garner enough public savvy and support to pass the initiative despite such a well-funded smear campaign.

The scale of the Portland Clean Energy Fund may have been another key to its success with voters. In Commissioner Hardesty’s experience as an Oregon State Legislator, she said she knew that the state hadn’t been able pass comprehensive climate-oriented legislation for 25 years. “We are in a wonderful position in Portland to really do things differently than we have done them in the past,” Hardesty told the audience, “and to do them in a way that is inclusive of all community members, of all community voices, and to be able to leave a legacy that our grandkids will be proud that we were the ones that moved this forward.”

Margo Craig contributed reporting