“I have a little cup of coffee and get up and walk the dogs. Then I get to work by nine o’clock. I go till noon, sometimes 1 o’clock. Then I pick it up again for another four or five hours in the afternoon.” Professor Eleanor Erskine, associate professor of printmaking in PSU’s College of the Arts, maintains a strict discipline of working on the craft each day in the studio. “When I get into it, I’m not very social,” says Erskine. “I just enjoy being in the work so much that all my senses are given over to it and I get really pulled in and excited by it. It’s kind of like having a really good conversation with somebody.”

“Once you drop it, it’s very hard to come back. That’s one of the reasons why I work every day. It’s natural, it’s like a second skin. It’s just what I do.”

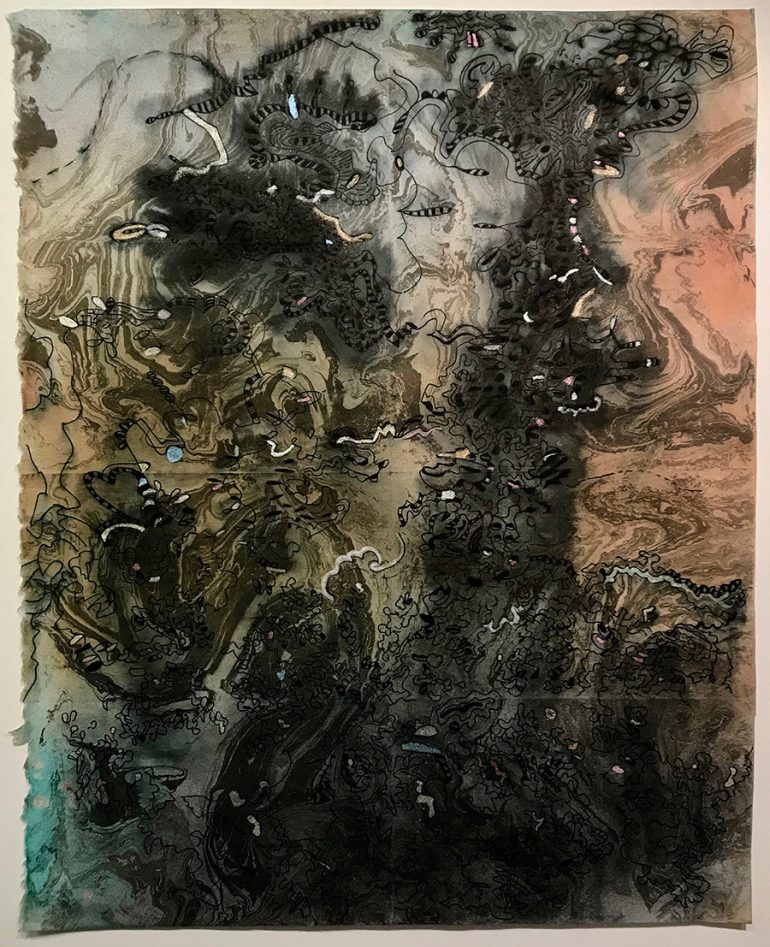

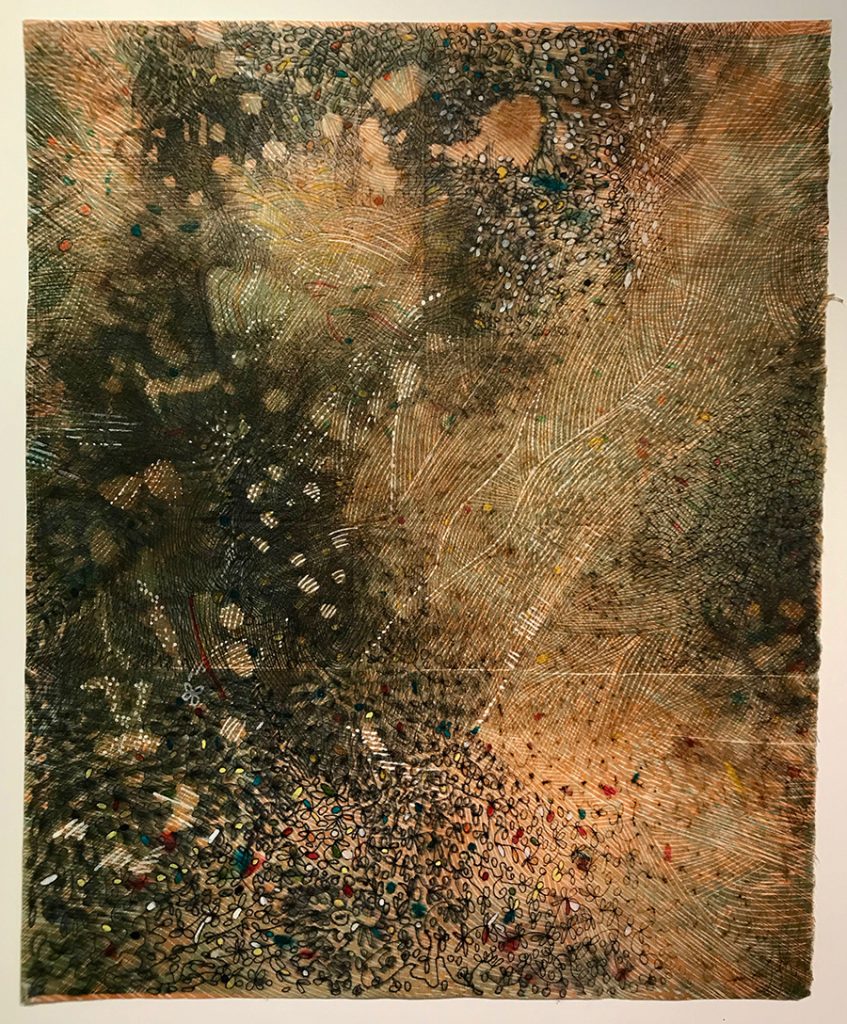

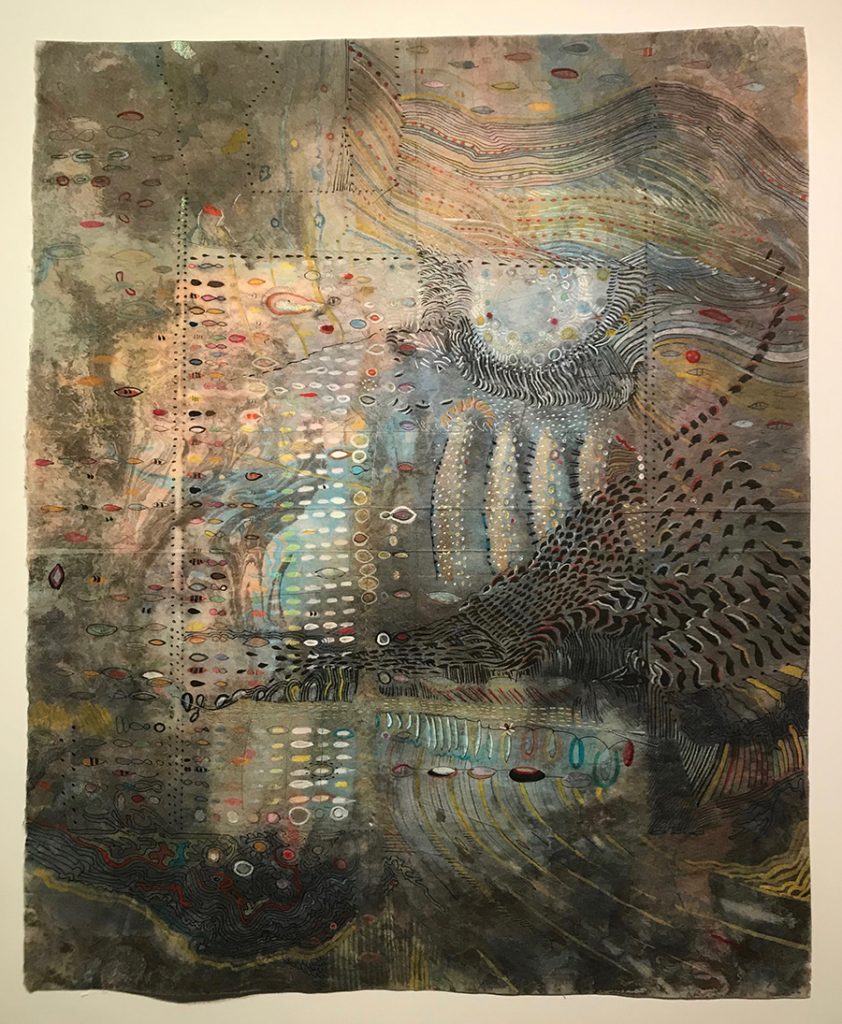

After over twenty years of teaching at PSU, this academic year is Erskine’s first sabbatical. The autumn and winter were frenetic as Erskine worked with Hugh Merrill (one of Erskine’s instructors during her undergraduate studies at Kansas City Art Institute) and Lisa Jarrett (assistant professor of Community and Context Arts at PSU) to prepare for their show On Drawing, which ran January 17–February 8, 2019 in the Littman Gallery in Smith Memorial Student Union on campus. With the show successfully complete, Erskine has returned to following the routine outlined above with the freedom to fully focus on the work.

Erskine goes on to further describe a day of work in the studio during sabbatical: “Time is such a funny component. We’re living in this time of instant satisfaction. I don’t live that in my work because I’m always building. One thing leads to another. One thing flows into another. I really want to let that happen. If it doesn’t happen, I need to let it be. A good day is not ruining anything, not getting off on another tangent, not starting something completely different. I have some guidelines, but I love to experiment.”

“I don’t think people realize how much work and growth happens when studying art.”

During her senior year of high school Erskine studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, which was closely associated with the style and philosophy of the Chicago Imagists. In 1981 she graduated from the Kansas City Art Institute with a BFA in painting and printmaking. For the next five years she worked for commercial printing artist Donna Aldridge, who specialized in color landscapes. “I learned a great deal about color from her,” says Erskine. “There was no health insurance, nothing. I was just working in a garage. But I learned so much.” As a subcontractor, Erskine made $10 per print, about fifteen to twenty percent of the sale price. “She’d send these all off to California,” says Erskine. “She was making over $100,000 per year.”

“I wanted to be sure that I could continue to make art instead of just jumping right into graduate school,” says Erskine. “I wanted to make sure I could work a job and continue to make my work before going to graduate school because I was afraid of the money. A lot of people go to graduate school right after their undergrad and they’re burnt out. I didn’t feel the pressure. I was still young.”

After the five years with Aldridge, Erskine matriculated at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. “I was 25 when I went off to graduate school,” says Erskine. “When I did I applied to all the top colleges and got into them all. It just worked out for me to be an older student rather than being a twenty-two year old. I’m really grateful. I think it’s smart because you know yourself better and you know what it’s like to work for a living. You start over. I think it’s healthy, it’s really healthy.”

At Cranbrook, Erskine studied printmaking under Steve Murakishi. “I’m still grateful to have had Steve,” says Erskine. “I was the only female in my class. When I first met him, he said, ‘I don’t want you waiting on all the boys.’ It was just one simple sentence and it was so sweet because I could have.”

She simultaneously pursued her interest in sculpture with Michael D. Hall of Hamtramck, Michigan. “A genius, to me a genius,” Erskine says of Hall. “I remember when I was first studying with him, I couldn’t understand a word he was saying. He talked about good Kirk and bad Kirk [referring to the exploration of duality in the Star Trek episode “The Enemy Within”] and art and he just tied it all together and spit it all out. And he’d bring in folk artists. He was always on the phone with Donald Kuspit, who was a big art critic and writer as well. So he was bringing in that stimulation. And he was bizarre. Long grey hair and a beard. He wore pink sportcoats and smoked.”

“People came there from all over the world and they were extraordinary,” Erskine says of her Cranbrook cohort. “Everything that I thought I knew about what art was went out the window because these people were making things and talking philosophically in a way that was just outrageous, exciting. It wasn’t necessarily even an object. There was one person in ceramics making art about nothingness. I really grappled with that. Those kinds of stimulating ways of thinking were there.”

“Making art is hard work…It’s a meaningful, deep process. You meet your soul there. That’s a pretty serious thing to find…”

Erskine speaks fondly of her Cranbrook mentors. “I think that’s a pretty top-notch experience to have, to make a connection to a teacher,” says Erskine. “To have someone that believes in you is pretty pivotal.” She has remained in contact with Murakishi over the years. “I could call him up tomorrow,” she says.

What kind of advice does Erskine have for students who aspire to work as professional artists? “You first have to be really dedicated to creating a disciplined work ethic. From there, things happen. If you think backwards—say, you need 50k to survive—I think you can figure out entrepreneurially how to make that happen. A lot of artists are willing to think non-traditionally: ‘The 9 to 5 job doesn’t work so great, I want to be in charge of my time.’ That’s the first sign that somebody’s trying to take charge of their own life. That takes a kind of entrepreneurial being and existing in the world. You can make things happen and make connections. There’s not just one way to do it.”

“The people who don’t succeed with it are mostly those that lack the discipline. Making art is hard work. I’m not saying you don’t enjoy it. It’s a meaningful, deep process. You meet your soul there. That’s a pretty serious thing to find, and to do it over and over and over again for the rest of your life. It’s like an excavation site,” Erskine says. “The practice time is really deep. Nobody sees that but you. Nobody.”

Erskine has seen students go myriad ways after graduating from PSU. “I’ve seen my students go on to graduate school, certainly. Some of them never come back to Portland, some of them do. Michael Endo is really interesting. He went on to Cranbrook. He came back and is now working for Bullseye Glass; according to Erskine he owns the gallery, but in the post linked here is the curator and in charge of a lot, but not listed as an owner; changed Erskine’s quotation accordingly]. He curates a gallery, he’s a mover and a shaker. He’s building a lifestyle that works for being an artist.” Some developed businesses conducted through Etsy or found yet other ways to make art without relying on the gallery scene.

“The practice time is really deep. Nobody sees that but you. Nobody.”

We also discussed our reading habits, with Erskine disclosing her current reading projects and past favorites. “I’ve read almost every book I possibly can on creativity and I still don’t know how to explain it,” says Erskine. “We don’t really know where it comes from in our brains. Lawrence Weschler wrote a book about Robert Irwin called Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees that’s brilliant. I think that’s what you have to do. When you’re first learning, you’re very conscious of this instrument playing this way.” Once one develops as an artist, says Erskine, one can create without having to think too much about the tools and the medium. One simply creates with whatever means are available, fully expressing the artistic vision without being restricted by lack of mastery of tools.

“Listening to your own energy is a really important thing for setting up a day,” she says about choosing the creative tasks on which to focus. “If I wake up feeling melancholy and want to stay in that, I wouldn’t run a jackhammer because that would throw it off completely. If I didn’t want to stay there, I might do some jumping jacks to get my energy shifted. It’s important to be in the body as a maker. So I have to listen to what it needs because that’s where the feelings come from for the work.”

What is it like when energy, discipline, and intent are all aligned? “When I’m deep in the work, it’s the best place to be,” she says. “It takes me away from everything else, but I can’t be there forever.”

To fully master a particular medium is to move beyond the intellectual approach to creation, she says. “You have to get to where it’s just all work and it doesn’t matter what it is because you’re whole and complete and present when you’re coming to it. It puts you into a place where you’re sensory. You’re not reacting with naming. It’s relationships. So it doesn’t matter if it’s paint or plaster as long as you can move. I really strive to model moving fluidly from one thing to the next and letting one thing evolve into the next.”

“That’s what I try to do. It takes time.”

More information about Professor Eleanor Erskine’s and her work can found at https://www.eleanorerskine.com/.