Vixens, not veal.

Sizzle, not steak.

We put the meat on the pole, not on the plate.

A zaftig woman with blue hair and breasts hanging over her bra sat on a low stool behind a podium, using a large phone covered in a pink case with cat ears. She introduced herself as Harlo and recited the rules of the club: no photography without permission; if sitting at the stage, tip the minimum during each song; no touching the girls, even if she touches you first. A poster stating these rules hung in front of the podium, next to a notice forbidding motorcycle club colors and insignia.

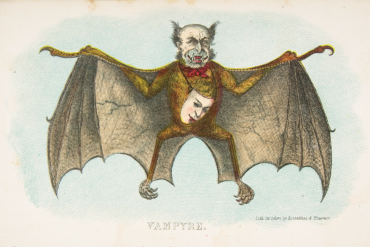

Harlo took me past a painting of a kneeling, red succubus into the club. Two women were on opposite ends of the stage and a Nine Inch Nails song—one from Pretty Hate Machine—was playing on the sound system. It was loud and the compression made it sound as if it were materialized in stone. The lights, naked women on an elevated stage, loud music, and garbled announcements over the speakers overwhelm the senses.

The ceiling of the main room is a peaked roof of dark wood. The walls nearer the entrance display swords, manacles, and other metallic, medieval contrivances. Booths and tables by the wall ring a stage with a metal pole at either end; there are always at least two performers onstage. Some performers do routines as a duo, sometimes with audience members. The bar is on the far side of the room, under a platform with trophies and a drum set. A painting of a caped demonic figure with red skin and horns hung above it all, visible from everywhere within the main room.

Everything under the red lights appeared to be that color. The paintings are predominantly red. Such lighting illuminates the club in a way that still seems dark, as if we are underground in a photography darkroom.

Harlo showed me to a booth marked as reserved and then returned to the anteroom. The performer sitting at the table introduced herself as Opal*. She began working a few nights per week at Casa Diablo in September on the recommendation of her friend, and now coworker, Tyler. She works as an office manager at a small company by day. “I don’t really need the money and I’ve always worked multiple jobs,” she told me. Regarding her sales technique, she says, “I make them fall in love with me,” in contrast to some who practice the hard sell. Her Friday night shift sometimes ends at 3 a.m., leaving her only four and a half hours until she begins her other job. Opal said that Casa Diablo, compared to other establishments in town, is “more R-rated.”

This isn’t your grandmother’s fully nude club.

Opal left and “Virtual Insanity” by Jamiroquai came on. Toward the table came Casa Diablo’s proprietor, Johnny Diablo Žūklė (a Lithuanian surname pronounced “zoo-klay”). We went outside and stood under a gazebo on the porch. Weathered paintings of succubi in various positions adorned the wooden walls encircling the porch.

Žūklė described his and business partner Carol Lee’s purchase of the Morrow Mansion in Salem to operate as a bed and breakfast. They planned to christen this inn Chateau Vegan, but a protracted legal battle over the finer points of county licensing laws quashed this plan. This vegan venture, however, is only his most recent. The saga of Žūklė the vegan began decades ago.

Johnny Diablo Žūklė became vegan in 1985, before knowing there was a word for it. (When he said, “Diablo is my middle name,” your faithful correspondent at first thought it was a joke, but a peek at an old driver’s license proved that Diablo is in fact his middle name) He told his mother and aunt that he would no longer eat or use animal products, and that he aspired to effect change in this way. “They said, ‘Don’t become a fanatic.’ Too late,” he laughed.

Over the next few years he learned about the history of veganism, a term coined in 1944 when Donald Watson founded the Vegan Society in the United Kingdom. “By giving it a name,” says Žūklė, “he allowed it to grow. Vegan is my favorite word; the other two are my daughter’s names.” He then showed a photo of his daughters, ages 8 and 9, on either side of the VegFest 2019 sign.

In 2001, Žūklė opened his first vegan restaurant, Vegan Terra, in the Rancho Palos Verdes city of Los Angeles county. “I may have been the first business with the word vegan in the title,” Žūklė says of this venture. It turned out to be an inopportune moment to start a business because Žūklė was “laying down tile when 9/11 happened.” He kept the restaurant open for a few years, although he says the location was not ideal and neither the word “veganism” nor its definition were yet familiar to the general public. Žūklė told a story about one customer’s praise for his falafel recipe at the time: “This is the second best falafel I’ve had. The first is in my home country, Israel.”

After deciding to close the LA restaurant, Žūklė scoured real estate listings in every region in the country, seeking an ideal location for a second vegan business. He nearly settled on purchasing an old, shuttered schoolhouse in Sugar Notch, Pennsylvania to remodel as a vegan bed and breakfast, but chose the other location under consideration, the house at 2839 NW St. Helens Road in Portland, Oregon. Thus the Vegan Terra tale ended and Žūklė moved north to begin anew in the Rose City.

Before this hillside house was a strip club with a diabolical name, Žūklė’s initial business in this location, before Casa Diablo, was a pirate-themed restaurant and bar called Pirates Tavern, which first opened on September 19, 2006 (International Talk Like a Pirate Day). Business was slow; of the small number of people coming in each day (most of whom were truckers and construction workers from the surrounding industrial area), a few people would look at the menu and leave when they saw there was no meat. “What a bunch of pussies,” Žūklė says of those who seemed averse to meatless food. 2006 passed into 2007, and the fortunes of Pirates Tavern, like those of restaurants everywhere, “started dropping.”

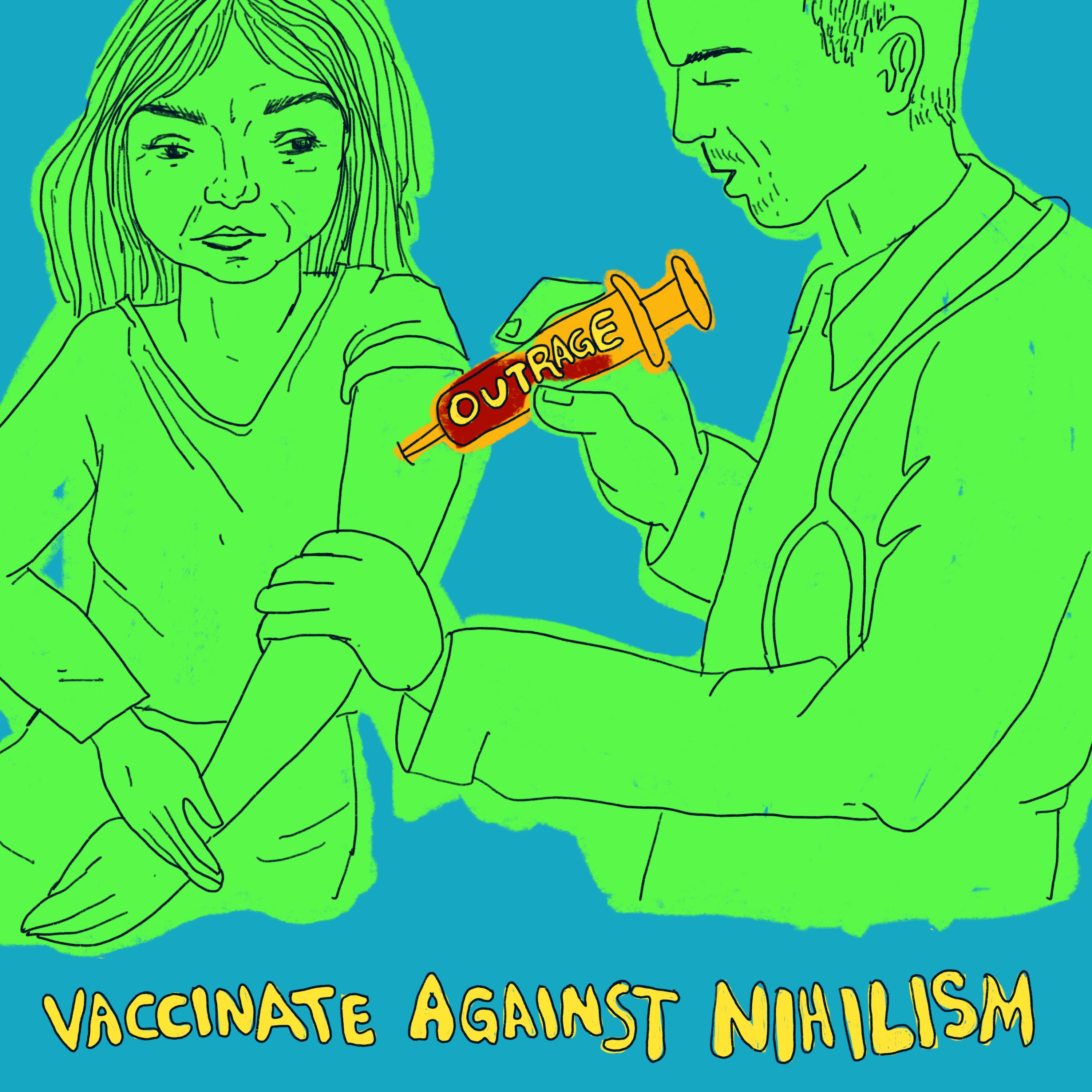

Amidst the uncertainty of the recession and the prospect of shuttering another entrepreneurial venture, Casa Diablo was born. “It was a last ditch effort,” Žūklė said. He thought that strippers would lure in the nearby truckers who were otherwise reluctant to go to a vegan establishment for the food alone. After visiting many of the other strip clubs in the area, taking note of what he considered the best aspects of each, Žūklė opened the newly christened Casa Diablo on February 1, 2008. “We were the first club in Portland to do girl-on-girl, and the first vegan strip club in the universe as far as I know.” One sign outside promised “Girls, Girls, Girls” and the other exhorted customers to “Bring Cash”—in those early days, the venue lacked an ATM. The novelty of a vegan strip club gained notoriety, receiving attention from IFC, Wild Travels, and The Daily Beast. La Gaité Lyrique even came all the way from Paris, France. “We went from zero to hero in five years. It’s really a pleasure and it’s been a good run.” Žūklė said that longtime patrons drawn in by the striptease eventually came around to trying the food on offer; the vegan element, although at the forefront of the online presence, is not explicitly stated in the menu. “It only took two years to get you to try it,” Žūklė said.

Žūklė emphasized that converting people to veganism is his primary aim. He exhorted those new to veganism to download the Happy Cow app to find vegan and vegan-friendly establishments. He also recommended reading the books How Not to Die and How Not to Diet. And don’t worry about achieving perfection: “There’s no perfect vegan; all you can do is try for perfection,” he said.

Of the growing awareness of veganism as well as the increasing number of vegans, Žūklė spoke approvingly. “It’s happening. We can’t be stopped. Being vegan is one of the best things you can do for the planet. I hope in the future that everyone will be vegan and we’ll look back and wonder how we could have been eating animals.” He sees Casa Diablo as his part of the great vegan endeavor. “I don’t fish for the bodies of animals, I fish for the souls of men,” Žūklė says, echoing the words of Christ in Matthew 4:19 and punning on his surname, which means “to fish” in Lithuanian. “We’re saving animals one bite at a time.”

We then reentered the club. Alien Ant Farm’s “Smooth Criminal” played while a woman with long black hair and tattoos on the backs of her thighs did an inverted spin on the pole. After descending, she made her way to the edge of the stage and straightened her legs, raising the stiletto heels with blocky toe-boxes into the air; she rotated her legs and her thighs jiggled. The men and women sitting at the rack threw money on the stage. “What a great place,” Žūklė said to me.

A different song came on and the performers rotated. There were two duos, one at each pole. At the pole closer to the club’s entrance, one woman was nude, but the other retained revealing top and bottom underwear pieces. They kissed and the partially clothed woman put her head between the other’s legs. People sitting around the stage hooted and cheered. At the aft section of the stage, a bearded man in gleaming white sneakers leaned on all fours, putting his face between the legs of a woman supine on the stage. Another woman sat on his back and spanked him.

“What are you doing—a scientific experiment?” a man next to me asked, indicating my notebook. “Are you enjoying your research?” One of the women at the forward section of the stage performed an inversion on the pole and slid down, resuming the kisses and caresses with her counterpart.

The dancers rotated again as Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean” came on. A performer with long dark hair and translucent platform stiletto heels took the stage. Her only tattoos were a pair of birds on either side of her pubic area, diving downwards. After her routine, she collected the money on the stage in a blue pail, the side of which read, “Whatever Happens.” There were several such buckets; each dancer used one to gather the bills at the end of her turn.

“Ladies and gentlemen, make some noise,” the DJ announced between each set. He had the number “13” tattooed behind one ear and a dinosaur tattoo behind the other. Between songs, he made loud yet incomprehensible introductions on the microphone. Occasionally a performer’s name was decipherable: Peaches, Katniss, Scarlet, Fame, and so on.

The Bee Gees song “Stayin’ Alive” came on. An Asian woman with long pigtails, wearing nothing but white sneakers took the pole at the forward stage. During the second verse (“I get low and I get high / If I can’t get either, I really try… It’s all right, it’s ok / I’ll live to see another day”) she climbed into the lap of a bespectacled man in a brown hoodie seated ringside; he removed his glasses during her visit and replaced them when she arose. During the song’s bridge (“Life goin’ nowhere / Somebody help me / Somebody help me, yeah.”), she again left the stage to sit in the lap of a man clad entirely in black. Two young women in midriff-baring tube tops sat next to him. They laughed and frequently looked at each other while shifting about in their seats. The song alternated between the exhortations to stay alive and calls for help as it faded out: “Life goin’ nowhere. Somebody help me. Somebody help me, yeah. I’m stayin’ alive…”

What is the appeal of strip clubs? What makes the business of looking at naked women so profitable?

Pornography is widely available; anyone with an internet connection can quickly and easily find sexually arousing images. With such convenient options near at hand (so to speak), people nonetheless choose to go to strip clubs. Therefore, visually oriented sexual desire alone fails to adequately explain the appeal of strip clubs. Other psychological drives are at work.

What, other than sexual desire, draws people to spend large amounts of money to sit close to women as they get naked to the accompaniment of loud recorded music?

Consider, in a broad way, the aesthetics of Western art from antiquity to the present.

Female nudes, often presented as Venus or Aphrodite, have been a common subject. Whereas the male nude often represents virility and heroic strength, the female nude evokes the sublime and the beautiful. The needs of the unconscious psyche cannot be rendered rationally, and thus we find ourselves drawn to performances (such as stripping) as an attempt to encounter the sublime.

The attraction for strip clubs, then, may be that people are seeking visions of the sublime in the way they best know how. In the electronic age, when images and video of anything imaginable are readily available, there must be something about seeing the nude women in the flesh that addresses a desire that simulacra cannot.

The nude female form exerts power. In Mark 6 and Matthew 14, the daughter of Herodias (traditionally identified as Salome) dances before Herod on his birthday, and he is pleased. He promises to give her whatever she wants; she asks for the head of John the Baptist on a platter. It would be a mistake to read the story as historically accurate, but it does encode in narrative the desire, danger, and power at play when a nude woman dances.

To turn to our own day, some critics claim that strip clubs objectify women and reinforce male domination and there is some truth to this. And yet in my visit, the women’s nudity controlled and directed the dynamic within the club; men are passive spectators whose presence is tolerated only so long as they can provide compensation for it. There is, therefore, a subtler power dynamic in which proximity to female nudity (anticipated and current) is the dominant force. Part of what seems to be for sale is not only the permission to view nude women, but the illusion of interest and intimacy, which itself must be provided while negotiating the sale of private dances and other additional services; it requires skill and a shrewd sense of psychology to conduct the business in little or no clothing and shoes that would make a podiatrist wince, all while affecting an invented, seemingly genuine persona.

photographs by Van Vanderwall

photographs by Van Vanderwall

The song changed and two performers rotated to the forward stage. One flipped into an inversion on the pole; her counterpart straddled a man’s face and then put her chest in the face of a seated, stageside woman. The seated woman wore a black skirt and a white sweater that fit snugly against her large breasts. A lady sitting at our table told Johnny that she wanted to see the sweatered woman remove said piece of clothing. He beckoned her over to the table and suggested that she get on stage. “I’m a welder, not a stripper,” she averred, before going on to say that she feels fat and out of shape after the winter holidays. Johnny Diablo Žūklė and the woman’s male companion insisted. She acquiesced and went off to prepare. On stage, a performer near the top of one of the poles was balled up around it in a fetal position, spinning and gradually descending.

When the next song began, the welder with the ample bosom joined two Casa Diablo performers on the forestage. “The devil made her do it,” Žūklė said to our table. Onstage, she leaned against the pole as one performer on her knees removed the skirt and the other struggled to remove the sweater. “Pull those titties out,” someone nearby said. The sweater came off, revealing sets of elaborate tattoos covering nearly all her dermal real estate. Her male companion and Johnny exchanged a fist bump. Her breasts seemed remarkably unaffected by gravity, as if conjured by the imagination. “She’s a natural—but is she really?” Žūklė asked with a grin.

The DJ continued to make thundering yet incomprehensible announcements. Performers rotated at the end of each song. “Kickstart My Heart” played. “Hash Pipe” played. Performers and songs came and went every few minutes. With anywhere from 35 to 60 women scheduled to perform on Friday and Saturday nights, the roster seems bottomless. Performers may have only two sets onstage on such a night, and thus the sale and performance of private dances occupies these lengthy periods of waiting. Protocol at most clubs classifies the performers as independent contractors whose earnings come entirely from tips while onstage and additional services such as private dances. Clubs do not pay performers a wage.

The legal classification of performers and their earnings has been contentious at Casa Diablo. Five years ago, Matilda Bickers and Amy Pitts, two former Casa Diablo performers, sued the club, alleging that the club financially penalized performers for infractions (such as tardy arrival and failure to disrobe quickly enough onstage), mandated kickbacks for bouncers, DJs, and management, fostered an environment of pervasive harassment, and failed to pay a minimum wage. Žūklė, according to Willamette Week, characterized the suit as “frivolous and ridiculous,” arguing that performers are “independent contractors in charge of their own business” and that the club is not required to guarantee a minimum wage.

This dispute over whether performers ought to be classified as contractors or employees continues. Willamette Week reported in March of last year that Bickers and Elle Stanger, a former performer at Lucky Devil, presented opposing cases to the Oregon State Legislature as part of hearings on bills to reform strip club law in Portland. Bickers advocated for the state to classify performers as employees, which would guarantee wages and, she believes, improve working conditions. Stanger claimed that the current independent contractor status allows performers greater earning potential and freedom to determine their schedules and their selection of clients for private dances, and is thus preferable to the proposed change to employee status. The report characterized the proposed bill as “dead,” but with many ongoing efforts either supporting or opposing strip club reform, the issue remains unresolved.

Working as a contractor does not bring many, if any, of the protections most professions assume is their due, such as unions, guaranteed breaks, safe working conditions, or even the certainty that the stipulated compensation will be paid without employing the arts of persuasion. And yet despite such travails, working as a contractor is, first and foremost, working for oneself, and therefore a greater form of freedom than being a clock-puncher of any kind. Contract work allows for greater earnings—through chance, industry, or cleverness—and rewards greater skill; for instance, a musician who can play from memory the dozen or so pieces most frequently requested at weddings will do better than one who does not know this material very well. Factors other than competence influence contractor earnings, but the point is that such things can increase earnings, whereas wage work tends to reward one’s ability to seem busy for the span of a shift.

Furthermore, wage work, despite the assumption of its great security and therefore its status as the contemporary labor norm, allows for greater exploitation of said labor. To draw on my own experience as a musician, I remember a particular gig for which we were employees on an hourly wage rather than a per-service fee; our pay was about a quarter of what this organization had formerly paid for the same work when it was classified as contracted and we still had none of the protections, like being able to call in sick, that such a change ought to have brought. Compared to contract work, it was worse for the band and much more profitable for our erstwhile employer.

I think employee classification for strippers would produce comparable results: less flexibility in scheduling; fewer opportunities for increasing earnings; lower overall earnings paired with increased taxes; no real workplace protections; and more opportunities for employers to set and enforce vindictive rules (such as requirements to work without clocking in). In addition, tighter workplace regulations for strip clubs would entail regular inspections by the relevant city, county, and state bureaus, and thus a profusion of paperwork—statements of income, certifications, licenses, and so on. Increased regulation would also mean that strippers, some of whom are reportedly making hundreds of thousands of dollars per year, would find their reported earnings under closer scrutiny, and therefore find themselves more likely to be audited or otherwise financially penalized.

Unless a more thorough set of reforms were implemented than simply adjusting the legal classification of strippers, the contractor status seems best for now. Such an infrastructure would likely resemble the manner in which SAG-AFTRA and AEA protect the welfare of film and musical theatre actors respectively. Without such a comprehensive restructuring of the law and labor-management relations, uncoordinated piecemeal changes will adversely affect labor.

Žūklė escorted me to the aft part of the club, near the queue of customers at the bar and a third stage, on which a tall, dark-haired woman with extensive tattooing seemed to be warming up for a routine on the main stage. He estimated that over the twelve years Casa Diablo has been in business, about 5000 women have worked there as dancers. Of the bartenders, kitchen staff, and other employees, most have been with the business for five to ten years. “We have very low turnover,” Žūklė said. He permitted a photograph of the Žūklė-as-devil portrait hanging above the bar and explained that the drumset on the elevated platform is a relic from the club’s early days of hosting live music. He said that the other location—Casa Diablo II: Dusk Til Dawn—will soon have live music on a regular basis.

“Thanks for being vegan, brother,” Johnny Diablo Žūklė said to me as I departed. In the anteroom Harlo continued to recite the rules to and take the $8 cover charge from newly arrived customers. Just outside the club entrance, a man sat cross-legged on the pavement, with his phone and wallet beside him. It was after midnight and raining. He was hunched over with the hood hiding his face. The parking lot was full, yet cars continued to pull in. Towering above the road and the club, the sign’s two female silhouettes and text promised “NUDE DANCERS.”

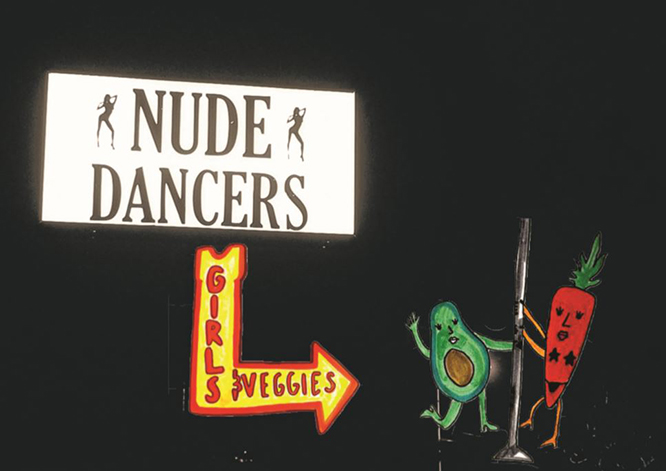

Illustration of dancing vegetable (is an avocado a fruit?) strippers on a pole by Greer Siegel. Photo of Casa Diablo’s “Nude Dancers” sign by Van Vanderwall.

* The names of performers used in this article are stage monikers, not legal names.