“So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them… And the evening and morning were the sixth day.” —Genesis 1:27-31

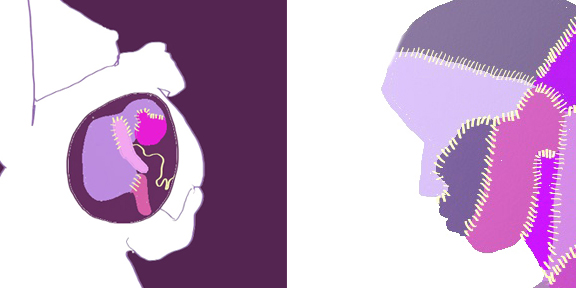

He Jiankui, a researcher in human genetics at China’s Southern University of Science and Technology, made a bold announcement at a November 28th, 2018 conference in Hong Kong. Dr. He claimed that his team had successfully used the CRISPR gene editing technique on twin human fetuses to bestow HIV resistance on them.

Performing this research without oversight broke with all preceding norms and ethical conventions. Whereas all human genome editing research entails destroying fetuses before viability, the Chinese team claims to have brought the twins to term. Dr. He also announced that an unidentified woman is currently carrying another genetically modified fetus to term.

Ethicists and researchers almost universally inveighed against He’s sidestepping of safeguards and peer review. The Director of Oregon Health and Science University’s Center for Embryonic Cell and Gene Therapy Dr. Shoukhrat Mitalipov made available a public statement calling the Chinese study’s outcome unpredictable and its methods lacking in rigor. A much-publicized remark by Professor Julian Savulescu of the University of Oxford characterized He’s gene editing experiment as “monstrous.” Such emotional language reveals not only anger at researchers for flouting ethics agreements, but revulsion with the children born of the experiment.

Many opinion pieces published in the immediate wake of the announcement of late November focus on Gattaca-style scenarios and so-called “designer babies”—the use of the gene-editing technology to create a child catered to the parents’ desires. What about the inverse? If genetically-modified humans become commonplace—as has already occurred for some commercially grown crops and animals raised for slaughter—will the first few “generations” be considered monsters as Dr. Savulescu’s comment implies?

To better understand questions of this scope, I turned to our wisdom traditions. Rabbi Michael Cahana of Congregation Beth Israel, a Northwest Portland synagogue in the Jewish Reform Movement, specializes in the interface of religion and technology and has served on committees in this field. “We have to think about the implications of the technology that’s going to have multiple generations of reality and pushes the definitions of what is human,” Cahana said. Cahana said he interprets Jewish scripture as permitting gene editing of plants and animals when utilized for the production of food, comparing this to the Green Revolution agricultural advances of the 1950s and 1960s.

Genetically engineering humans is a different matter. Cahana points to the Genesis 1:26–27 account of God creating man in his image as the core of how to understand human gene editing in a scriptural context. Being created in God’s image “can’t be a physical thing,” Cahana said. “It has something to do with our being different from animals. It is about a kind of eternality and a commonality, that we are all created in God’s image, not that some people are created in God’s image. It’s all human beings. When we start to redefine what it means to be a human being, we get into a real problem. Is this person in God’s image or not? We want to have a commonality of human beings and not create a separate species.” He was hopeful, however, that future gene editing research could address heritable and incurable diseases such as Tay-Sachs.

After further meditation, my own inclinations led me to a state of much greater skepticism over technology and so-called progress. Soto Zen priest and teacher Kodo Sawaki urged us not to “forget that modern scientific culture has developed on the basis of our lowest consciousness.” Our continued, unfounded faith that the next technological development will solve old problems without creating new ones is at the very root of the push for gene editing, as well as industries and societal trends (such as so-called smartphones and social networking) beyond the scope of this article. “Advancement is the talk of the world,” said Sawaki Roshi, “but in what direction are we advancing?”

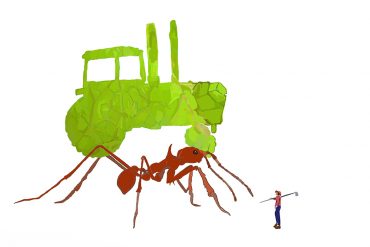

Let us attempt to comprehend human genetic engineering in light of a past technology, once radical but now well-entrenched: the automobile powered by an internal combustion engine. When this technology was first introduced, advocates promised a less physically grueling and more efficient future. Lo and behold, the technology came with an appetite of its own; the very landscape has been hacked, flattened and paved to make smooth the way for the parking and driving of these contraptions. Did anyone foresee global warming? Did early innovators and technologists foresee global conflict for access to fossil fuels? What about the immense amount of time and money individual people spend on everything from trying to find parking to purchasing and maintaining a vehicle to sitting alone in traffic on smoke-choked roads amidst a crowd of others doing the same? Nobody foresaw such problems until their effects were so widespread and commonplace as to go unnoticed.

There are old clichés about some things cutting both ways and being mixed blessings; every blessing is mixed and everything cuts not just both, but in all ways. Not even the greatest thinkers predicted the ramifications of internal combustion engines, and the same applies now to genetic engineering of humans (and any organism for that matter). Perhaps altering the genetic code, even for ostensibly benign purposes, such as addressing inherited diseases, affects other less easily measured traits such as the ability to empathize with others, fall in love, or have a sense of humor. Whatever changes are wrought by human genetic engineering will forever become part of the gene pool; there is no closing this box after opening it.

What role will corporations and governments play in genetically modifying humans? Monsanto, now a subsidiary of Bayer, copyrighted their genetically modified soybean and corn strains in the 1990s; the company has sued farmers for patent infringement and theft of intellectual property for not paying a licensing fee to grow said strains. Would genetically modified humans constitute an invention, for which someone holds a patent? Would courts rule then that people are inventions or intellectual property also constitute property, and are therefore a valuable living asset like a racehorse or purebred dog? Would this give rise to legal international trade of modified (or unmodified) humans?

Whether laws forbid designer babies or not, the very existence of the technology in the presence of a desire for perfect children will necessitate this as a phenomenon. Will enhanced people be “better”? As Cahana asked, what makes a better human being? What is “better” when applied to people? Is creating a child for the purposes of competing and generating income in a capitalist system good for the child, the family, the society, or the species?

The history of class systems privileging certain skin colors and body types above others leads me to conclude that a prevalence of baby-designing would result in a flattening of human genetic diversity through the creation of people that fit current models of beauty and success.

Leslie Jamison’s article for the December 2017 issue of The Atlantic investigates sociological patterns that emerge in the life-simulation game Second Life. Despite virtual reality’s promise of the creation of “an equal playing field, free from the structures of class and race”, the game’s “preponderance of slender white bodies” speaks to the underlying social construct of “whiteness as invisible default” that is simply reinforced in the game.

A video game is not genetic engineering, but it does provide us with an analogous scenario: Given the opportunity to create any new world imaginable, people will tend to work with the value systems and markers of success of the old world. Does a future of baby-designing portend the same bland, whitewashed world as this virtual reality experiment? Would it not make more sense to remedy societal and cultural problems rather than building a race to meet arbitrary (and highly flawed) standards of beauty and worth?

I leave you with more questions than answers, but this is as it should be. Our technological society currently sees only purported answers in each new development, remaining blind to the potential questions and ramifications. Dwell not in simplistic hope in technology, forget not the dreadful consequences of previous technologies such as the internal combustion engine and nuclear energy. Consider what tampering with the human genome portends for next one, 10, or 100 generations.

Until He’s announcement, we lived in the age wrought on the sixth day. What hath the hand of man wrought after the sixth day?