The Stonewall Uprising did not incite the movement for LGBTQ rights, but it did lay the groundwork for that movement to actualize, and spark the initial boom of open queer activism in the early 1970s. Because of this, Stonewall, despite not being the true conceptual moment of the fight for LGBTQ rights, exists as a symbolic beginning.

In the years since, queer communities have mythologized the uprising in various ways. For example, the unrelated death of pre-Stonewall era “gay-icon” Judy Garland a week before the start of the uprising is widely considered a metaphorically important aspect of Stonewall—one era has passed away; a new one must now begin. Furthermore, various accounts credit different individuals as the person who triggered the uprising’s beginning. Marsha P. Johnson, Stormé DeLarverie, and Sylvia Rivera are all contenders. However, rather than view these different accounts as historical discrepancies, they are all accepted the way apocryphal variations of a mythology are accepted; the point, after all, isn’t who started the uprising, but that it happened. So though it remains a well documented and paramount historical event, The Stonewall Uprising, alongside its historical importance, has also achieved culturally multifaceted relevance. It’s history. It’s culture. It’s art.

Last month, I stressed the importance of queer individuals and allies having a continued willingness to live their lives openly—an importance emphasized in the work of Ugandan activist Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera. Openness allows society to see people for more than who they are perceived to be, and debunks the misconceptions of fear society holds in the idea of “the other.” One way queer individuals are able to express their identity, while simultaneously demystifying themselves to their surrounding societies, is through art. In the United States, art addressing queer subject matter is increasingly gaining acceptance from mainstream audiences. Take for example the 2016 best picture nominee Moonlight, or the acclaimed 2013 interactive novel / video game Gone Home. But this ability for LGBTQ people to use art openly is mostly a post-Stonewall phenomenon; queer identities and art have a relationship our culture is still exploring.

Queer identities were not absent from mainstream American art prior to the 1969 uprising, but the few present identities were often shrouded in a thick code of subtext and innuendo, presented so shallowly as to merely serve as an easy punchline, or simply ignored outright. The Stonewall Uprising helped create a desire to use art as a means to more deeply, directly, and honestly explore queer topics in culturally influential ways—it helped queer art come out of the closet. We in the U.S. are lucky to have communities that are accepting of queer art, but this reality is one many LGBTQ individuals around the world have in only limited capacity, or do not have at all. Because of this, greater recognition is needed for queer individuals who commit to out-of-the-closet art in places around the world where it is not always safe to do so, individuals like dancer and activist Abhina Aher.

Abhina Aher, opening doors in India

The mythologies, histories, and ancient works of art in India are populated with a variety of queer identities, often in ways that would strike modern observers as being obvious. For example, the hero figure Shikhandi is born female but takes on masculine roles, enters into a heterosexual relationship with another woman, and in some version of the myth, exchanges physical gender with a benevolent male spirit. In light of such stories, it isn’t surprising that India has long recognized the existence of gender identities outside of biological males and females; in 2014, India even passed The Rights of Transgender Persons Bill, which offers greater freedoms and rights to transgender and third-gender individuals. However, transgender and gender non-conforming people continue to face discrimination and be viewed as less-than by much of current Indian culture. Despite improvements in legislation, there remains a divide between queer peoples and the greater society—a divide Abhina Aher knows first hand.

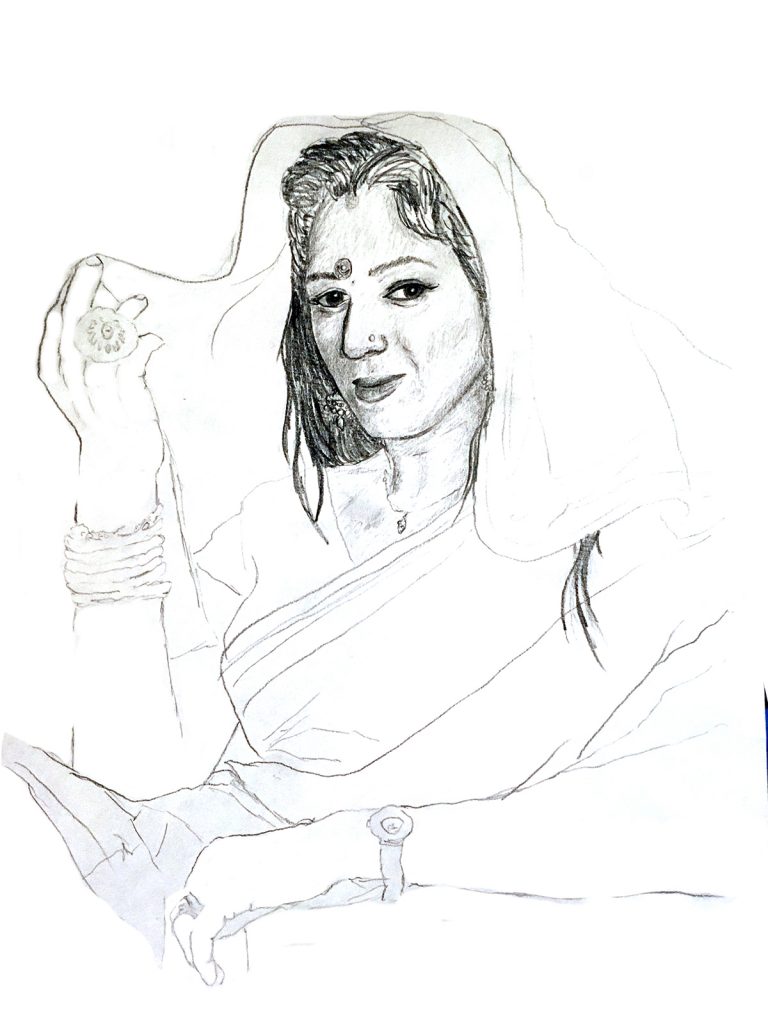

Aher was born biologically male in Mumbai, India. Even at a young age, she* recalls feeling an affinity for the traditionally feminine, as well as a fascination with the professional dancing her mother did to earn extra income. As a child, Aher would hold performances of self-choreographed dance routines for friends and neighbors. However, these feelings and interests were strongly discouraged by her mother, and, as Aher grew into adolescence, by her society. Eventually, Aher began to suppress these expressions of self.

Her repression of feelings and interests intensified after a group of male students forcibly stripped her and both verbally and physically abused her while on school grounds. Aher reported the incident to the school, but was herself ultimately blamed for the attack. In an interview with NPR, Aher recounted, “[A teacher] said to me, ‘Your friends are doing this because you are behaving in an extremely feminine way and that’s what is an issue.’” The school ultimately did nothing about the incident.

Despite feeling a deep discomfort with a masculine identity, Aher learned to appease her family and her society by living life according to traditional male roles. But Aher found this way of life too oppressive to keep up long term. Shortly after graduating from the 12th Standard (equivalent to high school), Aher attempted suicide. She walked out into the ocean and tried to drown herself, but was rescued by passersby who witnessed the attempt. This event, though traumatic, was a turning point. At just 19 years old, Aher concluded that she would need to live life as who she was, regardless of the consequences she knew she would face.

Aher and her mother both openly admit to having a severely strained relationship for about 10 years after Aher came out. Aher clarifies that her mother was facing the strong social stigma of having a queer child. Along with the strain of her relationship with her mother, Aher was also unable to find consistent work because of her transgender identity. As a result of this, she eventually found herself in sex work. In her later activism, Aher would emphasize how common it is for transgender people in India to work in the sex industry. Sex work, alongside begging, is one of the only ways, despite background or level of education, that transgender individuals in India can earn consistent income. However, Aher was able to free herself from sex work after finding a support system in the Hijra community.

The Hijra community in India—dating back to antiquity—is a community comprised of transgender and intersex people, who are culturally and legally recognized as a third gender. Before the colonization by Great Britain, Hijras were thought to have special communication with the gods; for this reason, Hijras commonly danced at weddings, births, and other celebrations as a way of spiritually blessing the ceremony. Dance remains an integral part of this historical, cultural, and artistic community.

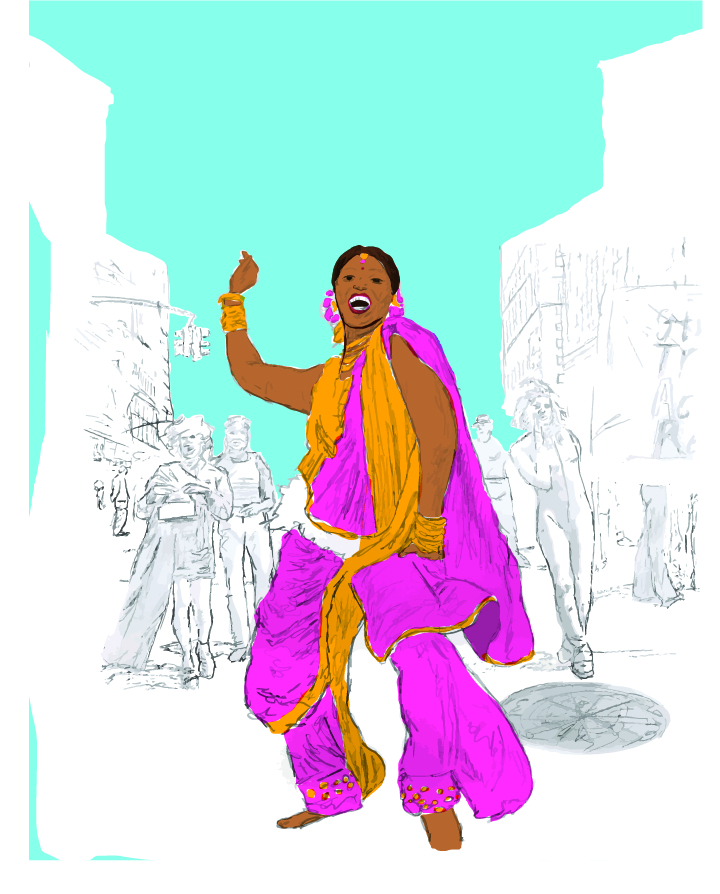

Aher realized that the Hijra community’s history with and specialization in dance could be used not only to connect transgender individuals with one another, but also to explore their identity and struggles through a medium of art that itself could, in Aher’s words, be used to “bond this [transgender] community with the larger society.” In 2009, with the help of other members of the Hijra community, Aher founded Dancing Queens, an organization that both employs skilled transgender people who are having trouble finding work, and helps its transgender members learn trade skills for jobs in their communities. Its primary focus however, as the name suggests, is dance.

Dancing Queens has since become known for its use of dance to explore the struggles of transgender and queer individuals in Indian society, as well as the struggles that society itself must overcome in order to fully recognize and accept these individuals. For example, one of the troupe’s dances explores the difficulties of coming out to one’s parents as queer, and the difficulties those parents often face in learning to accept their queer child; quite appropriately, the dance is usually performed by Aher and her real-life mother, Mangala Aher, who has since become a strong advocate for LGBTQ rights.

Since its founding, Dancing Queens has performed close to 100 shows across India, and its performances have opened up conversations about queer issues in various communities. The troupe’s advocacy and art have made tangible changes in India and laid the groundwork for Aher to become a nationally recognized LGBTQ advocate.

She has since become a full-time associate director of sexuality and gender rights at the India HIV/AIDS Alliance. This position gave Aher the opportunity to conduct statistical analyses of queer populations in India, which various organizations have been able to use in order to provide better care and resources for these populations. In 2017, she was recognized as a “Global Innovator” by the Human Rights Campaign. Aher continues to dance, and continues to use the medium of dance to positively change the lives of queer individuals and change the outlook of societies around India and the world.

Why we still need art

There are many aspects of a culture that work to define that culture, but none more so than art. Throughout history, art has played a significant role in all cultures, whether that culture be defined by borders, beliefs, identities, or diasporas. So, too, has this been the case for queer peoples. In the half-century since Stonewall, queer communities in the U.S. have begun to create works of art that directly—rather than passively—explore what it means to be a member of such a community.

Queer communities have even begun to give themselves features of mythology through emphasizing symbolic aspects of their history, as is the case with the Stonewall Uprising. And while art that belongs to a culture helps to identify and define that culture, art does something more than this—something many communities, especially queer ones, still need in this historical moment. Art opens doors.

Art is not only a medium for communities to explore the narratives of their own lives, but a medium through which to communicate a deeper understanding of those narratives to the society in which they belong. Aher’s troupe Dancing Queens strives not only to give meaning and voice to the Hijra community, but also show that the Hijra community was and is a unique and positive aspect of the greater Indian culture. Similarly, queer art here in the U.S. has the ability to open the door between queer communities and the society that rejected them—the society that is still learning to accept them.

“What we have done is that we have put a foot inside a door, which is a door of hope, and we will open it—very, very soon.”

—Abhina Aher

* When speaking English, Aher prefers feminine pronouns, hence why they are used in this article. However, as a member of the Hijra community, Aher considers herself third-gendered rather than female.