Finally, the perfect book volume to resurrect 1990’s film discussion lounges…

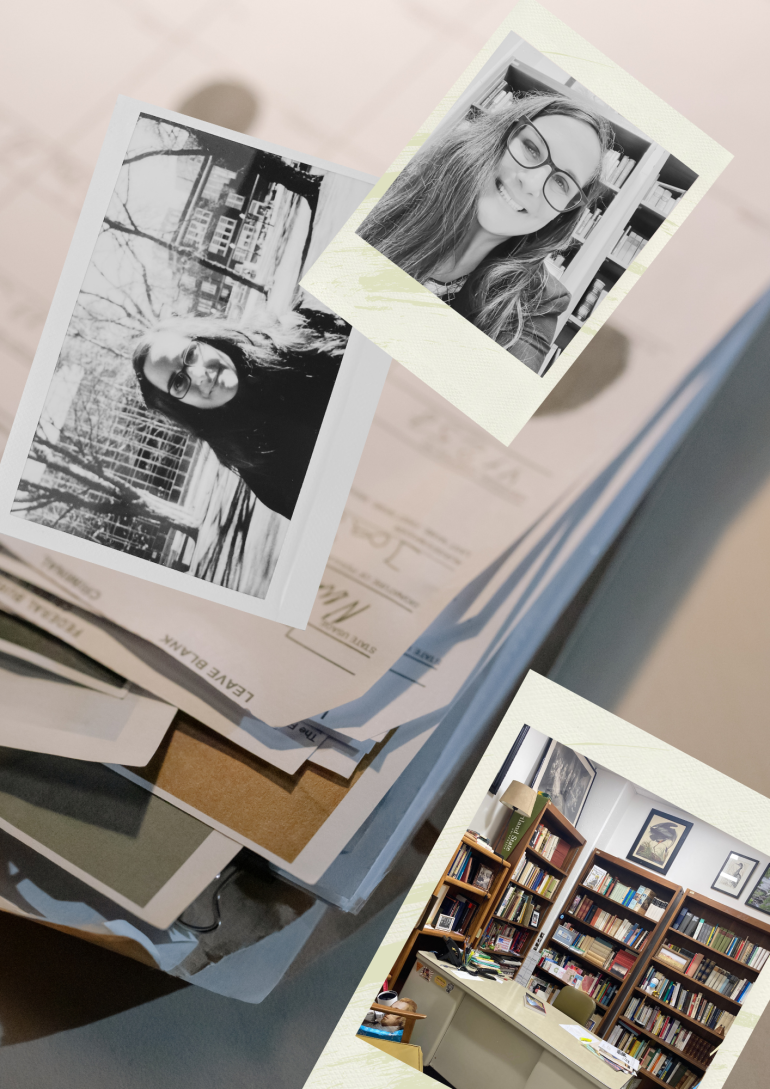

This month, for a second article in the DISCOVERED series, I invite you into the clever world of the German department professor, Carrie Collenberg-González. Her contribution within the volume, Moving Frames, was DISCOVERED in the neatly arranged display on the 3rd floor of the PSU library with a well made sign, denoting that the collection was of, “PSU AUTHORS” that has inspired this series….

Carrie Collenberg-González is the co-editor [along with Martin P. Sheehan] of Moving Frames, Photographs in German Cinema. This is a pivotal volume!- that few are talking about, yet.

Side note: I have to tell you right off the bat that as I was reading Moving Frames and interviewing Professor Collenberg, I became slightly obsessed with resurrecting a 90’s style film discussion group akin to one I attended in San Francisco. It was a secret society. We got dressed in our best, walked down an alley, met a door man, said a secret word, were whisked into an elevator, taken up a number of floors (N=some number!), released cordially into a bar and screening room, where we spent the next 2.5 hours enjoying an intimate screening of a film (usually Noir), libations and heavy discussion, not to mention new found friendship.

After hearing Professor Collenberg’s take on photography, I would personally like to invite you to read this book and meet me, (future real, and currently in imagination) on the Nth Floor secret discussion lounge to discuss it. (Imagine your favorite libation in hand). Let us proceed, now that we have gotten comfortable.

The press that published Moving Frames, Berghahn Books, was introduced to me by this title and author. “Berghahn has established itself as one of the leading academic publishers in German Cultural Studies”, said Collenberg. The Moving Frames chapters were written by different scholars who recognized what a unique book this was in the field. Collenberg explained to me the exciting story of making the book become a reality “I was talking to Martin P. Sheehan at the German Studies Association. We are both interested in cameras, photographs, and film and realized during our conversation that there was nothing on photography in German cinema yet. We both love collaborative work and submitted a proposal….” The result is a book that anyone would be very proud to have on their shelf. I consider it as a rarely addressed book, myself, and a potential starting point for a serious discussion group on the rare works of German cinema, and also on photographs in the films. “The chapters in the book really go into things you just wouldn’t see the first time. Most people are not used to seeing a plot through its relationship to photographs. It opens your mind to so many other things.” There are iconic German films well known for their incorporation of photographs like People on Sunday, The Legend of Paula Paula, and Run Lola Run. But it was important to us to work outside of the canon and bring other films into it, to show how ubiquitous this really is.” An idea of the authors was to include the lesser known films that were under acknowledged (or wholly unacknowledged). “There are not many places [in the public eye, where] these films get mentioned.”

Professor Collenberg’s own chapter in the volume analyzes three films that collectively fall into the category of ‘Heritage films’. Collenberg said, “Heritage films are a popular genre in Germany and the United States, i.e. Killers of a Flower Moon is one. They are usually beautifully shot films about a historical period and are often meant to convey a certain agenda…” After completing a reading of this ingenious work, one will likely, like myself, begin to notice how this selective subgenre works differently from its counterpart subgenres in German film history or from the scrutiny of the public eye in general. Other qualities which make a film “Heritage” in quality include that it is, as Collenberg writes in the volume, “integral as a structuring agent for historical trauma and memory.” She further writes that German Heritage films are a “self enclosed world”, and in this case that the construction of a national cinema is, “presented through photographs in these three films. The three Heritage films eloquently analyzed by Professor Collenberg in Moving Frames are:

Yasemin Şamdereli’s Almanya – Willkommen in Deutschland (2011)

Wolfgang Becker’s Good Bye, Lenin! (2003)

and Max Färberböck’s Aimee & Jaguar (1999)

(links here are to watch them for free.)

Here is where you watch the films….perhaps at our collective new-fangled temporarily imaginary Nth floor film lounge? Ok, stay home and watch. I won’t spoil the whole of any plot and just give you a brief synopsis on these films, from the Introduction and also Chapter 8 of Moving Frames. If you wish, you can imagine sitting with your favorite libation in a cool skyrise, though, listening to Professor Collenbergs’ special analysis just for us…

“Aimee and Jaguar…(based on Erica Fischer’s best selling book)…is one of the most conventional of the Heritage films because it specifically deals with the Holocaust,” says Collenberg. In the book she writes that it is, “…a series of flashbacks based on the reanimation of photographs from [protagonist] Lilly’s private collection that transmit her memory of Felice [her Jewish lover] to the viewer.” Collenberg continued in the interview with her description, “this film goes through a photo album, and tells the story through pictures. It’s such a beautiful analogy and shows how we also often tell our story through the pictures of our lives. In the film, we are literally walking through Lilly’s photo album of her pictures with Felice, just like we might spend an evening looking at old photographs and reminiscing about the past.”

In Good Bye, Lenin!, Alex, the 20-something son, attempts to suspend a GDR reality for his mother who fell into a coma hours before the wall came down. She comes out of the coma but the doctor warns Alex that any shocking news (like the wall falling!) might create a cardiac arrest, so Alex convinces an aspiring filmmaker friend to manufacture fake news that portray his mothers’ awareness of ‘reality’ and slowly bring her into the present to assure she is not shocked by the extreme news that the wall fell while she was in a coma and the GDR no longer exists. This irony of having the freedom to choose to manufacture socialism, is what truly drives the action. Collenberg explained“ The film is all about how visual representation tells stories but I am interested in specific examples of a chiastic process – the beginning of the film shows seven postcards of East-German streets and the end shows shots of the real streets. So it goes from dead (or still) to living (or moving). The same process is repeated with the protagonist Alex’s mother. We see her staging and posing for a photograph in the middle of the film and then we see the photograph in the end after she has passed. She goes from a moving image to a still image. This is important for the meaning of this film and understanding Alex, a boy’s coming of age and his attempt to deal with the loss of his mother and country.”

For the third film, Collenberg says:” ‘Almanya, Welcome to Germany,’… is just so poignant…It starts right away with photographs of first generation Turkish kids doing things German kids do. The film uses photographs to place them into culture. There are scenes that insert the father Hüseyin (a Turkish guestworker) into historical footage–and it’s really playful. But then a profound beauty of grief and time and family and generation just hits you — especially at Hüseyin’s funeral where you see the characters standing with their past selves as children…” The main protagonist, Cenk Yilmaz, is a young boy with an old soul who drives the action with his introspection of all of these realizations and connections.

Film is therapy in general. There’s no way around that. Professor Collenberg spoke of Aimee and Jaguar, which depicts the main character at the beginning as a present day vignette, transitioning from her home to a retirement community. This is when the film starts walking through the photographic album that Aimee refuses to give up when she moves to her last stage of life, clutching the memories of Jaguar in the bundle of photographs. “When you’re talking about trauma, this is called a screen memory.” Collenberg told me. “We are remembering history but only remembering the surface. There is something below –that triggered these pictures- that is the real thing that we are confronting….[Trauma is…] the thing that happened. You repress that part but hold on to the memory you have repressed…” …It’s amazing how pictures get used in this way. This is an extreme example in understanding a German individual’s relationship to the Holocaust. We don’t know Jaguars’ story because she didn’t live to tell it, we only see it through Aimee’s perspective – the perspective of a German woman. Obviously Aimee loved Jaguar, she has thought about her her whole life. But it’s the photographs that really mimic the structure of memory and the creation of history.”

How can we understand the connection between art and trauma? Behind thin veils of disassociation lies real and very critical human states of complex mind. One of the best ways to study trauma is through film, perhaps. Collenberg and I discussed trauma in film. Collenberg’s work deals not only with the effectiveness of photographs but also with how films from Germany and their exposure to the viewer are as a sort of soft heal that grows exponentially through watching and analyzing films that were made for the understanding, or processing of trauma.

Have you seen a photograph in a film and not been significantly affected by its presence, its change-making power? The reasons for incredible movements of emotions when we see photographs in films are addressed in various theories that I only began to scratch the surface in learning about when reading the Moving Frames volume and also in spending the lovely hour with Professor Collenberg hearing her take on all of these related topics and also on photographic theory. Further writing in the Introduction, Collenberg and Sheehan illuminate that, “photographic theory often deals in…binaries—not just stillness/motion, but also life/death, truth/fiction, past/present—and their inherent tensions that only become more compounded in film. Photographs problematize the borders that seem to separate the binaries, thereby bringing attention to these borders.”

To delete or not delete the following chunk

I asked Professor Collenberg what her favorite chapters were in the book–not to exclude any of the equally incredible authors at all, but simply to offer you the deepest level of tease possible for this exceptional book (and it’s over two dozen references of films it analyzes specifically or effectually). She wished to share on, “the two that deal with east Germany, “THE TRANSGRESSION OF OVERPAINTING; Jürgen Böttcher’s Radical Experiments with Intermediality in Transformations (1981)” Matthew Bauman did a really good job putting that together…and articulating some of the ideas behind it and how to understand Bottchers’ work, an avant garde artist in the GDR.”

Further, Collenberg reminisced, “I think that chapter paired with Anke Pinkert’s Chapter 11 “POSSIBLE ARCHIVES; Encountering a Surveillance Photo in Karl Marx City (2016)” Her article is so smart, she is an expert in East German culture, she does a great job taking this really personal experience that the person has in the documentary film and contextualizing that in a larger political framework….”

Collenberg added, “I’m a fan of horror films so I think the Rammbock one is great. “VIOLENCE, DEATH, AND PHOTOGRAPHS; Capturing the (Un)Dead in Rammbock (2010)” (by Melissa Etzler). [Also] I like the idea that Curtis L. Maughan talks about in the Afterward.“TOWARD A CAMERA LUDICA’; Agency and Photography in Videogame Ecologies,” the move into digital and the move into video games.”

To conclude, I would like to share one last inspiring vignette that Professor Collenberg shared in the interview I had with her. It is something beautifully shocking but rings true not just for the present and future as we know it, but in reference to the aesthetic richness of this eye-opening book.

“Photographs are over! This book in itself mourns photographs and is a tribute to photographs that existed in the 20th century that now don’t really exist anymore. They do, but in very different ways. So, I think the book will be important in another fifty years when we look back to ask how people in the 20th century thought about photographs and how this generation remembered and recorded history. The fact that looking at photographs in films is a topic, is because we can finally understand it as a topic. Meaning there has been enough distance to recognize that this is a topic to explore. It’s really hard to see things while they are happening that are different because you haven’t recognized it as different. So in a way the project is part of a larger mourning project, a grieving project for this nostalgia, or time past as well..”

To consider this powerful quote and also perhaps if you’re wondering how to put film analysis into your life, I found this quote in a separate book and chapter, New Directions in German Cinema. I feel it helps to understand the role you and I play in the consumption of and creation of film analysis. Our job as viewers is not over when we watch a film, according to Alisdair King.

What was once a film in a movie theater, then a fragment of broadcast television, is now a kernel of psychial representations, a fleeting association of discrete elements: […] The more the film is distanced in memory, the more the binding effect of the narrative is loosened. The sequence breaks apart. The fragments go adrift and enter into new combinations, more or less transitory, in the eddies of memory, the more the binding effect of the narrative is loosened. The sequence breaks apart. The fragments go adrift and enter into new combinations, more or less transitory, in the eddies of memory: memories of other films, and memories of real events. ~Burgin (2004:67)

This seems to indicate that by reading and creating film analysis we keep the value of the film alive. Thankfully, the concerned authors who contributed to this volume, Moving Frames, with Professor Collenberg and Martin P. Sheehan, did so and effectively raised these films to renewed recognition and assured they fall less fragmented in the collective ‘psychial representation’. Their job is done. Now, to complete the task, we must read (and discuss over libations). I highly recommend a lighthearted or committed reading of the marvelous analysis and survey in this volume, Moving Frames. (see below for the film discussion idea)

MORE ABOUT PROFESSOR COLLENBERG:

When Professor Collenberg is not busy creating fascinating writing projects, she is teaching German, being creative with her kids, and umpiring for Mt. Hood Little League. Her story of learning German, visiting Germany was inspiring. “My family is part of the 4th language in Switzerland- Romansch-” she says, “which is [spoken by] less than 1% of the population. “I became interested in German Expressionist art, especially Käthe Kollwitz, The Bridge, August Sander, and Walter Benjamin. I started studying with experts in the 18th century and loved learning about the beginning of aesthetic theory and Romantic and Gothic literature. Professor Collenberg has recently finished three other projects that you might be interested in on the Netflix series Babylon Berlin and American artist Frank Stella’s reception of German author Heinrich von Kleist. She is currently engaged in a research project on the 1810 Tales from the Dead anthology that inspired Frankenstein and on depictions of Doppelgänger in the 1913 film The Student of Prague.

HOW TO EXPERIENCE MOVING FRAMES

The recommendation I have is that you watch the films listed in this article, then, buy the book and read Professor Collenbergs’ Chapter 8 in the book –which corresponds. Then read the Whole Volume! Then, in your toupe, martini in hand, land on the Nth Floor, i.e. some private venue and proceed with a film book club to walk through this volume. Be the resurrection of 90’s habits you want to see.

ABOUT THE DISCOVERED SERIES:

You just read the second of the DISCOVERED series about amazing PSU professors who have published books (not just journal articles). Sadly, last fall, the PSU libraries’ “PSU AUTHORS ‘ shelf was disassembled against any power (of my dear effort) to prevent it. The allure of the collections’ extinction (with its, so far, mysterious original curator looming somewhere), has driven me to recreate it here for posterity! I write this series to inspire ongoing value in PSU professor creativity! I also hope that if you visit the library and fill it with energy, and you think this idea is worthy, perhaps you might join me and suggest a resurrection of the “PSU AUTHORS” collection. (Power in numbers)