“We know that we did not do enough to protect user data,” said Sheryl Sandberg, Chief Operating Officer of Facebook, and it didn’t take much for her to admit this to NPR’s Steve Inskeep. It is already known that our data is being used in exceedingly clever and often unsettling ways with microtargeted ads—it’s no coincidence Facebook targets users now for the very products and services they recently Googled. Since this massive microtargeting power comes from the Facebook data itself, the responsibility of protecting user data belongs to Facebook. What many didn’t know was that Facebook’s data was secretly slipping into private hands seeking more than just your dollar. When news of the Cambridge Analytica scandal broke, the New York Times reported an estimated 50 million Facebook users’ data had been illegally obtained and used for manipulating U.S. elections, but that number has steadily risen to 87 million.

In the beginning, Cambridge Analytica was just another third party company with limited access to user data. It began in 2014 as a political consulting firm “using data to change audience behavior.” Its status as “just another third party” changed in 2014 once the company began using these massive amounts of illegally obtained Facebook user data. News broke in March 2018 when former employee-turned-whistleblower Chris Wylie revealed Cambridge Analytica as a “grossly unethical experiment.” As Wylie says, it is through the unique combination of microtargeting and scientifically informed psychological constructs that many—seemingly one in four—Americans were targeted not just as voters, but as personalities. Before seeing Cambridge Analytica’s pernicious behavior clearly, there must be a careful look at the situation and its characters

Facebook claims to be blindsided by the scandal just like everyone else, though its record raises some suspicion. Before 2007, all of Facebook’s user data containing pictures, statuses, likes, and so on was isolated and contained within Facebook alone, accessible to only its respective users and the Facebook officials who stored it. In 2007, Facebook allowed third party developers to gain access to virtually all user data, which changed everything. Over the next few years from 2007 to 2011, reports emerged that Facebook had been abusing user privacy and data. Confirmed by the Federal Trade Commission, this abuse included: Facebook overriding user preferences to turn private information public, lying to users that third party security had been verified when it hadn’t, sharing user data with advertisers and then lying about it to users, and the list goes on. Since it obviously didn’t maintain a decent ethical standard by itself, the FTC held Facebook accountable in 2011 by placing mandatory regulations on its activity.

It would seem all is well with some Facebook regulation in play, but trouble found another way to manifest. While Facebook itself may have indeed been playing by the rules, the site was unfortunately used as a conduit for malintent. It’s now evident that during the 2016 U.S. presidential elections, a building in Moscow full of Russian social media users (linked to the Russian government) used Facebook to spread misinformation in order to distort U.S. voter perception. Forced to acknowledge the reality of such events, Facebook could no longer downplay the presence of fake news on its site—a strategy they had employed to dodge the issue altogether. Indeed, now that Facebook acknowledges its role in the spread of misinformation, it claims a responsibility to address the issue. Sandberg now bolsters that Facebook is “not waiting for government regulations” to take industry-leading steps in being transparent to users about political ads, affiliations, and the like. Despite how technically accurate this claim is, Facebook is making these steps after news broke to the public of its mistake. This is a little too late to be commendable. There is a sense of concealed misconduct subtly present in Facebook’s attitude in these two infringements: first caught by the FTC in 2011, Facebook was forced to make amends, and now, Facebook cooperates a little more preemptively, but again, only after getting caught in what it knew was misconduct. Should we see Facebook to be a selfless innovator interested in protecting user privacy, as it suggests we should, or something else, perhaps a cunning corporation merely becoming more familiar with the legal system it’s increasingly caught up in?

Unlike Facebook, Cambridge Analytica was intended for political powers from inception. Not unlike Facebook, however, Cambridge Analytica also has its own disconcerting record. Take Alexander Nix: first a director at SCL Group, then left to create the associated company Cambridge Analytica. Nix has been moved through the corporate family ropes. On one hand, SCL Group, formerly “Strategic Communications Laboratories,” describes itself as a “global election management agency.” On the other hand, Cambridge Analytica “uses data to change audience behavior,” specifically in the context of elections. If they sound related, it’s because they are. It appears Nix gathered a background in this type of work first in SCL Group, and then created Cambridge Analytica where he would be more in control.

Seeing an opportunity in 2014 to use Facebook user data as the engine for his company, Nix directed and manipulated the information in a way that generated millions in profit through supporting exclusively Republican political agendas. His strategy had three big steps to success: First, Nix was determined to convince Robert Mercer, one of the world’s richest billionaire Republican donors, to provide the financial support fueling Cambridge Analytica; Mercer gave tens of millions of dollars on the condition that Cambridge Analytica serve only Republican politics. Secondly, Nix went on to convince Steve Bannon, Mercer’s political advisor, to join the company. By setting up a fake office in London, Nix and his employees successfully manipulated the company’s appearance so that Bannon perceived it as more academic, successfully recruiting him as vice president. (In fact, Bannon’s warped perception in associating the company with Cambridge University was why Bannon chose the name “Cambridge Analytica.”) Aleksandr Kogan was the final component of creating the company powerful enough to manipulate an entire country’s political process. Kogan had special access to much more Facebook user data than normal third party apps because he was a University of Cambridge academic; once Kogan joined Cambridge Analytica, this privilege was used as a loophole for exploiting user data far and wide.

Kogan, however, only had permission to use this data at the University of Cambridge. This is where Facebook gets wrapped up in the transgressions of Cambridge Analytica: accessing the data of 87 million Facebook users was only possible because of Facebook’s own involvement. As many know, it’s money from advertisers that keeps Facebook in business. To keep this business, Facebook creates a market around knowing user preferences gathered from “likes” and other data. Advertisers then pay to take advantage of this market, but there’s a common misconception of how Facebook handles these operations. While some may think Facebook sells the data itself, this is mistaken. Instead, Facebook sells a service. Advertisers tell Facebook what type of audience they want to reach (people into kayaks? Bicycles? etc.) and Facebook uses the knowledge of everyone’s interests to make sure the ad is shown to the right crowd. Much like the phone operator directing a caller’s line, Facebook sells their service (not user data) because they’re in the perfect position to help. That being said, Facebook gave up the power it had as gatekeeper by allowing Kogan the special privileges that he ended up abusing. Cambridge Analytica went on to create “psychographics” of all those users and without most of them knowing. The scheme started with simple surveys distributed across Facebook, where users were paid two to five dollars for volunteering their information. Little did they know as they took the survey, they volunteered not only info from survey questions, but every speck of data Facebook stored about that user and all the data of every single friend they had as well. As Wylie put it, “we would only need to touch a couple hundred thousand people to expand into their entire social network, which would then scale [Cambridge Analytica’s reach] to most of America.”

At first glance, a company consisting of a handful of people with access to more data than they could prowl through in their entire lives is one thing, but the computing power to turn all of this illegally obtained data into “psychographics” depicting a chilling level of detail about every user is another. The Guardian reported “When users liked ‘curly fries’ and Sephora cosmetics, this was said to give clues to intelligence; Hello Kitty likes indicated political views; ‘Being confused after waking up from naps’ was linked to sexuality,” and this is only the beginning. Clearly with all the data from 87 millions users, there is a lot of ground that could be covered, but what does it really mean for Cambridge Analytica to approach people “not as voters, but as personalities,” as Wylie put it? Ultimately this is not just about a company “trying to change your behavior” politically, because anyone could try to do that, and seeing it happen is not at all unusual. That’s the typical story of so many talk shows, agenda-driven media outlets and political parties, right? What Cambridge Analytica aimed for was far more subversive in a way that has never before been seen. Now, before going into what made their tactics different, it’s important to realize that none of them are illegal, at least as the story so far goes. For now, the only allegations facing Cambridge Analytica and SCL Group are issues of foreign interference, claiming that the companies violated U.S. elections law by allowing its chief executive, Alexander Nix, and other British employees to play significant, decision-making roles in U.S. campaigns. The other allegation is that the Facebook user data was illegally obtained. Again, how the data was used has not been found illegal.

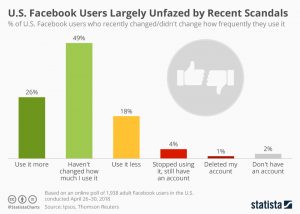

Richter, Felix. “U.S. Facebook Users Largely Unfazed by Recent Scandals.” Digital image. Statista Infographics. May 8, 2018. Accessed August 2, 2018. https://www.statista.com/chart/13780/change-in-facebook-usage/

In the words of Wylie, the company’s innovative use of the data was to use it to identify target voter groups, and design targeted messaging to influence [their] opinion… we would know what kinds of messaging [users] would be susceptible to and where you were going to consume that, and then how many times we needed to touch you with it in order to change how you think about something.” After the “engineering” team (data scientists, psychologists and strategists) created a message according to your psychological vulnerabilities, it then went to a the “creative” team (creatives, designers, videographers, photographers) to create content with the message, and finally to a “targeting” team who creates websites, blogs, and anything else that’s necessary, all laid out for the target audience to find. Wylie went on to call the entire operation a “full service propaganda machine,” so incredibly unlike “sharing your opinion in the public square, letting people come listen to you, and having that shared experience of your narrative.” Ultimately, Wylie says, the collateral damage is our shared experiences and mutual understanding. Without these, how can a society be functional?

In bearing witness to organizations like Cambridge Analytica (and maybe others), it becomes clear that such an approach to changing political opinions attempts to achieve the science of changing opinion. The idea that there could be a science like this seems to oppose the very existence of freedom. If science aims for repeatable results under the same conditions, then the science of Cambridge Analytica would aim to have a population (indeed, most of America) change its thoughts, beliefs, and votes, all on demand. To treat a human being as merely a bundle of psychological processes, where each can be controlled and determined, is to violate their free will through subverting it. If it is through science that a human being can be reduced to a set of cogs waiting to be aligned however the mechanic sees fit, then Cambridge Analytica attempts to use science to operate on humans as if they were a mechanical puppet, not free individuals to be engaged with. In the end, how can Americans be free if they are seen as objects to be operated on, rather the people to be engaged with? And without that freedom, how can they be fully functioning human beings? Since reports emerged, both SCL Group and Cambridge Analytica have closed operations. Facebook officials have given statements to many media outlets, Zuckerberg himself attended a congressional hearing on the matter, and overall the company has already started adjusting its approach to privacy. However, no matter what adjustments are made in the near future, the more lasting impression on history has already been made: Cambridge Analytica marks the first massive attempt at using computing power within the ocean of data in one of the most sinister ways imaginable. Even if Cambridge Analytica never returns, what will come of this power having already been revealed to the world?

this article originally appeared in the print edition of our June 2018, issue.